Changing face of fentanyl: The silent killer moving in Tampa Bay's Black communities

According to LIVE Tampa Bay, the opioid overdose death rate for Black Floridians increased 330 percent from 2014 to 2018.

When it comes to drug use, addiction does not discriminate. However, the factors leading to it can.

New research shows deadly opioid overdoses are rising fastest among Black Americans, and experts say the pandemic made it worse. According to LIVE Tampa Bay, the opioid overdose death rate for Black Floridians increased 330 percent from 2014 to 2018.

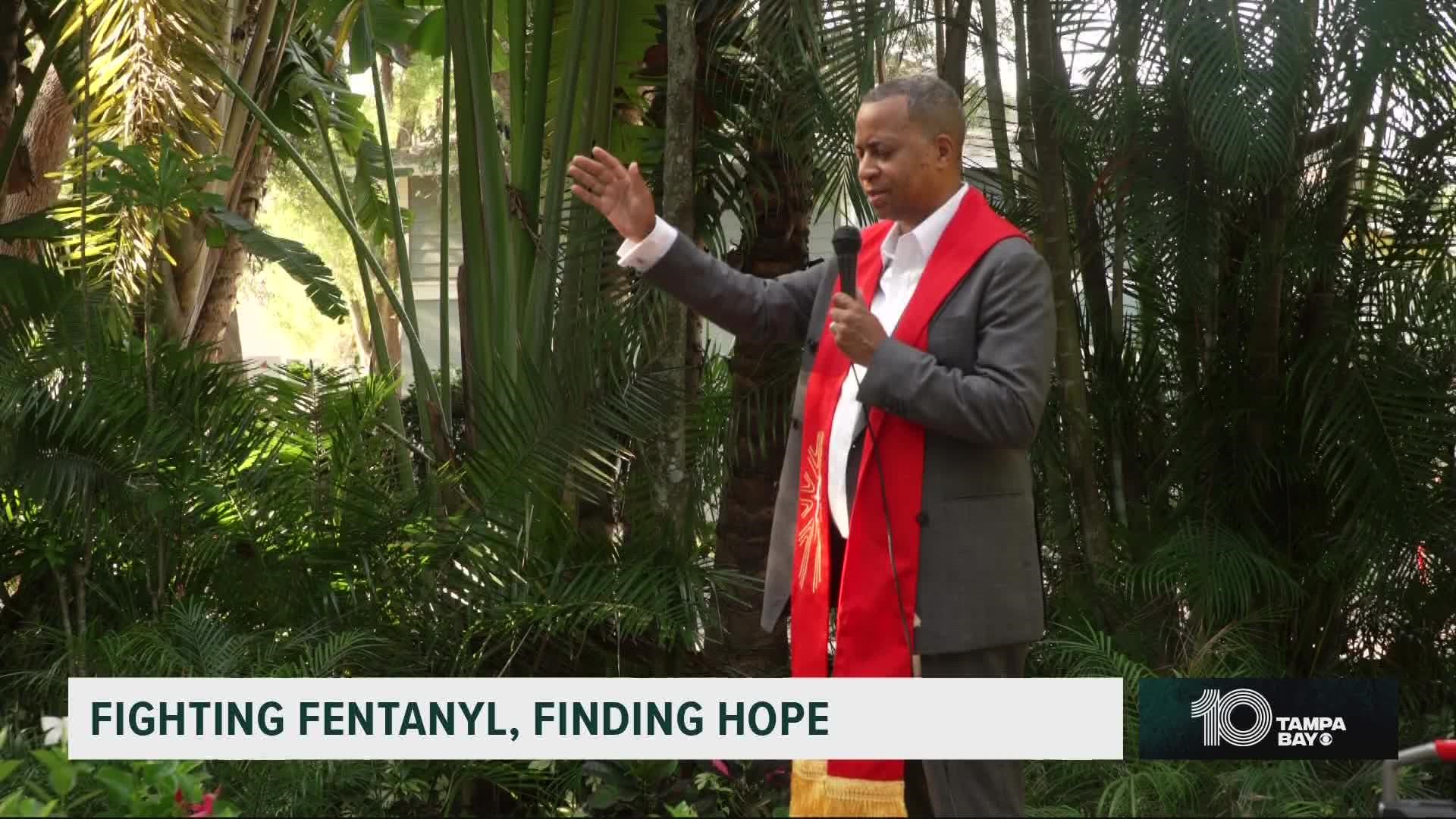

"How this crisis affects our community is different than another community," said Rev. J.C. Pritchett, president of the Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance of St. Petersburg.

The Pandemic's Epidemic A growing number of Black Americans are dying from fentanyl overdoses. Experts say the stress of the pandemic made the problem worse.

Sunday mornings in churches across America have looked a lot different throughout most of the pandemic.

"...Several things happened with the global pandemic: We weren't gathering on a regular basis as we do in our tradition at worship on Sundays," Pritchett said. "That's a support system several times a week that literally was removed from our community."

It was an amplified level of distress Pritchett said many Black communities have faced over the last two years.

"We’ve seen suicide rates go up in the Black community, we’ve seen overdoses go up in the Black community, compounded with COVID-19, compounded with the economic crisis," Pritchett said. "All these things are happening in the community all at once."

Pritchett, who works with community groups on fighting the local opioid crisis says he's compelled to fight the issue head-on. He says drugs have been a taboo topic in the church for too long, but it will take more than prayers to find solutions.

"I think it's very easy, to be honest with you, to focus on communions, weddings, funerals, Sunday School...and not deal with...the tragedy of homes are being broken because of drugs," he said. "We can't pretend that it doesn't exist because it does."

Researching the Problem, Finding the Solutions A new center at the University of South Florida will study addiction in communities of color

On the other side of the bridge in Tampa, Dr. Micah Johnson is working nonstop to understand the wider impact of drugs in Black neighborhoods.

"There has been an alarming, dramatic, striking increase in the availability of fentanyl in the Black community," said Johnson, an assistant professor in the Department of Mental Health Law & Policy at the University of South Florida.

However, the rise has happened so fast — Johnson says it's been tough to get an accurate picture of the issue.

"...We don't quite understand the impact it's having because we haven't been able to do the research fast enough to keep up with the epidemic,” he said.

That could soon change.

“We have the largest and most effective research education program, specifically looking at addiction in the nation, right here in Tampa at USF.," Johnson said.

Johnson is heading the Substance Misuse and Addiction Research Traineeship (SMART) out of a new laboratory at USF. Through a $1.5 million federal grant, he says the Johnson Lab will hold one of the largest clusters of African American researchers in the country studying the impact fentanyl and other drugs have on marginalized populations.

"We have a 2,000 square foot laboratory space that's exclusively for us to understand the issue of drug use in Black and BIPOC communities and other communities that have unique challenges," he said.

Confronting the Past USF researcher says systemic racism in Black neighborhoods influences how drugs are distributed and the community's access to treatment.

Johnson says fentanyl, among other opioids, is especially harmful in low-income Black communities that formed as the result of racial segregation.

"The leading scientists in the world on this issue have tied a direct line from systemic racism to fentanyl in the Black community," Johnson said.

Black neighborhoods have increasingly become prey for illicit fentanyl distribution, Johnson says.

"In regards to fentanyl, specifically, that I think the Black community is targeted by the folks who run these industries. I think that it pivoted to the Black community as potentially a new customer that was not as protected, or it was less risk associated with victimizing this population than other populations."

According to CBS News, most of the chemicals comprising fentanyl are made in China and shipped to Mexican cartels before illegally crossing the border into the United States.

Johnson says neighborhood drug dealers who often make headlines usually not responsible for bringing drugs into their communities. He says while they are still culpable, it's important to take a larger snapshot of how and why they decided to sell.

"Angels and demons. It's not that simple...There's people on both sides and there's a lot of overlap. A lot of dealers are also users who are suffering from addiction just like the people they sell drugs to," Johnson said. "We need to understand their stories, need to humanize them so that the community as a whole can be more healthy."

Johnson says it's also important to make sure the community has access to educational resources to address the fentanyl crisis.

"I've heard folks mention the widespread availability of drugs, but the lack of healthcare services--not just therapy, but any sort of healthcare services in their communities, and that's a huge problem," he said.

Johnson says when people can't find healthy ways to treat their problems, illicit drugs sometimes become the alternative.

"Medicines are fundamental to how human beings throughout time have dealt with pain and sickness," he said. "Why would people turn to these [illicit] substances? One: they don't have access to alternative means of coping. Two, even if they have access, they may not know that they have access."

Stealth Recipe Researchers say increase in deaths tied to more poisonous street supply.

Many people who overdose on fentanyl never intended to take it.

It is increasingly an ingredient in counterfeit drugs or other substances like cocaine or marijuana.

"The fentanyl is so powerful that it's used to cut and mix with other drugs to maintain a certain potency," Johnson said. "Fentanyl by itself. It's just a very powerful, potent drug. It's 50 to 100 times more powerful or potent than morphine."

Drug experts say these toxic drugs are also becoming more accessible to children.

"We know that these fake counterfeit prescription pills are widely available on social media," DEA administrator Anne Milgram told CBS News. "If your child is on TikTok or Snapchat or Instagram or Facebook, drug dealers can access them there. And that — it's almost like Uber Eats, being able right now in America to get a fake pill delivered to your doorstep."

Deja Vu Fentanyl is not the Black community's first crisis.

Fentanyl isn't the first opioid crisis to hit the Black community. Johnson says heroin devastated lives during the 70s and 80s, but the community didn't get much support.

"The face of the opioid crisis at that time was poor Black people," Johnson said. "Therefore, it was met with a lot of insensitivity, no resources, no humanization and locking people up and treating them like animals."

Anthony Breland says he knows this firsthand.

"I started out first drinking and then marijuana, and then by 11, I was sniffin' heroin," he said.

Breland is a client at the Tampa Bay Academy of Hope in Hillsborough County, Florida. He says heroin was a popular street drug in the Brooklyn, New York, neighborhood where he grew up. He said he used drugs to cope with his internal struggles.

"My intentions were more or less for a sense of enjoyment or for a sense of fulfillment, or to kind of like be able to deal with my feelings of worthlessness inside," he said.

Finding Hope Addressing factors that lead people to drugs is key to addressing misuse, researchers say.

Hopelessness is a common theme among those who use misuse drugs, according to both Dr. Johnson and Rev. Pritchett.

"Folks who are hopeless are four to eight times more likely to misuse opioids,” Johnson said. "For those who feel hopeless, they turn to these drugs to escape that hopelessness and to escape their sense of depression."

Johnson says addressing the social stressors that are leading people to drugs as a means of coping with their struggles is key to helping them overcome abuse.

Pritchett agrees.

"There are people who have casually, in the midst of all this hurt around us, slipped into this space of weakness and now their whole lives, the lives of their children and their community has been turned upside down because of it," said Pritchett.

Emerald Morrow is an investigative reporter with 10 Tampa Bay. Like her on Facebook and follow her on Instagram and Twitter. You can also email her at emorrow@10tampabay.com.