Fentanyl overdoses soar. Does Florida need safe places to use drugs?

10 Investigates takes a deep dive into an overdose prevention strategy that might sound counterproductive at first: Giving people supervised places to do drugs.

People are overdosing on fentanyl in record numbers.

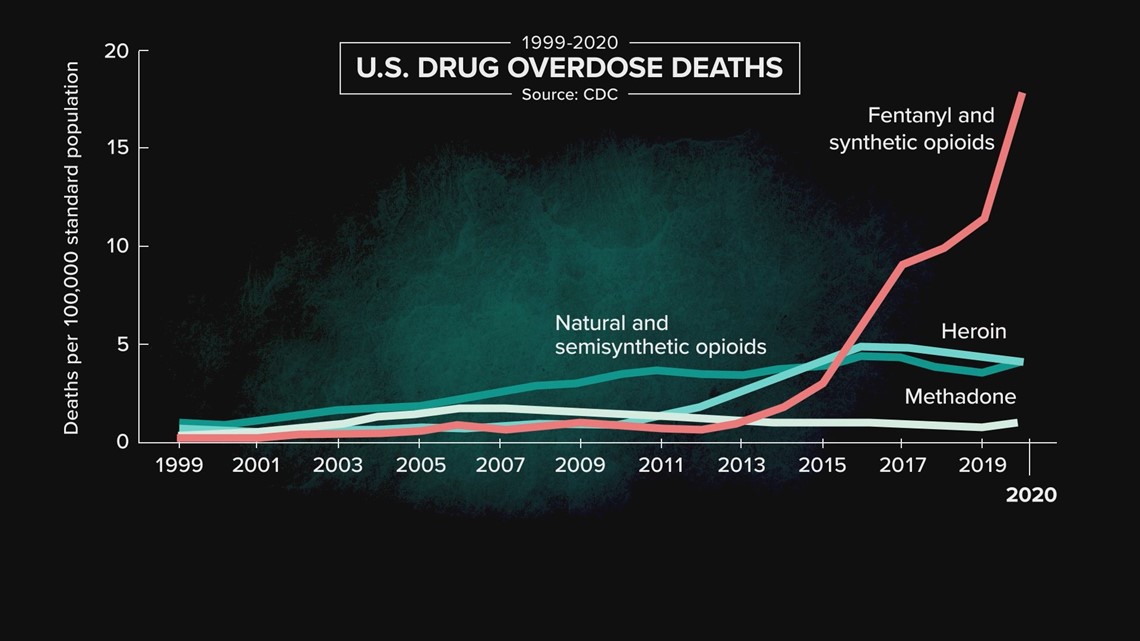

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data shows the rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, mostly fentanyl, shot up 56 percent between 2019 and 2020.

What we’ve been doing to prevent these deaths clearly is not working. So, how do we keep people alive long enough to make it into addiction treatment?

10 Investigates is taking a deep dive into a strategy that might sound counterproductive to you at first: Giving people safe, supervised places to use drugs.

It’s a strategy that other countries have been using for decades to prevent overdoses.

So, why has the U.S. been slow to consider overdose prevention centers? And why is nobody talking about this here in Florida?

Inside an Overdose

Parsons Park in Brandon holds a lot of memories for Mattie Velasco. These days, the park also holds new meaning.

“I used to come to this park all the time when I was little," Velasco said. "And later, when I was in my active addiction, I would come here to seek refuge and use drugs. And now, this park has taken on a different meaning. Because I have now, in recovery, been able to take my children here. I have been able to bring other women here to do step work and talk about recovery."

Now in recovery from her addiction, Velasco told 10 Investigates she overdosed on fentanyl six times that she can remember.

“However, I actually lost count of the times that I overdosed,” said Velasco. “A fentanyl overdose is instantaneous. Before you even realize that you’re overdosing, you are unconscious…It was terrifying to wake up and discover that I had overdosed. Because each time that I overdosed, I was actually alone. And so, I didn’t have anyone there to call for help.”

Velasco says supervised use could save lives.

“If there is an overdose that takes place, someone is there to call emergency services. Someone is there with Narcan to reverse the side effects,” she said.

Prevention Centers

It’s a strategy that goes by different names, including safe injection sites, overdose prevention centers, and safe consumption sites.

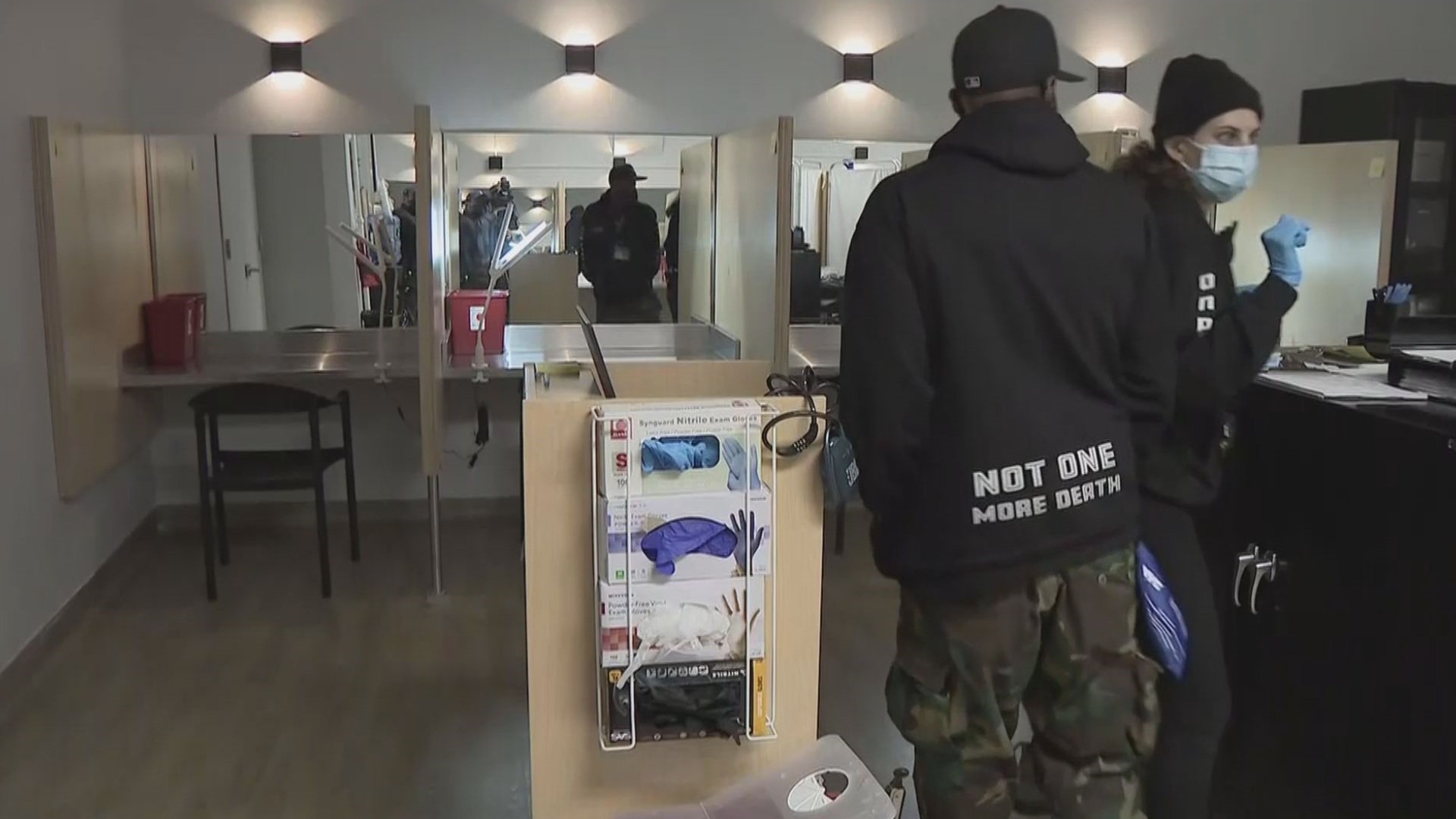

They’re facilities where people go to use drugs under the supervision of trained staff.

Those staff members monitor users for signs of an overdose and intervene if they start showing symptoms.

“Typically, these facilities provide drug users with clean injecting equipment, safer use advice, also emergency care in the event of an overdose, and referral to appropriate social healthcare and treatment services,” said Dagmar Hedrich in a 2015 European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction video that features an overdose prevention center in Barcelona.

Overdose prevention centers have been around in Europe for at least 30 years.

There are more than 120 overdose prevention centers in 10 countries, according to the Drug Policy Alliance, a U.S. organization “promoting alternatives to the war on drugs.”

The organization also says no one has ever died of an overdose at any supervised consumption site, worldwide.

Skepticism

Even within the recovery community, there are mixed feelings about this strategy.

Brandon Spencer is a Land O’ Lakes father who says the pull of addiction was overwhelming.

“It turns into this phenomenon of craving, which is a craving beyond my physical control," Spencer said. "I’ll literally be walking to go get some and telling myself I’m going to lose everything. I’m going to lose my wife. I’m going to lose my kids. I’m going to lose my job. I’m going to be homeless. I might die. Like all these – and I just, I can’t stop them feet from moving. I just can’t stop them."

He said overdosing on fentanyl was his wake-up call to get into recovery.

“For the first time in my life, I was scared to die. And the pain caused by that experience equaled a consequence great enough to motivate me to do something different,” Spencer said.

Having access to an overdose prevention center would have enabled him to keep using, he explained.

“It would have hindered me. It would have given me another justifiable reason to continue to get loaded. See? The doctors are watching me. It’s OK,” said Spencer. “The solution can’t consist, partially, of the problem.”

Decades Behind

The U.S. is decades behind other countries on this prevention center strategy.

A lot of research has been done on overdose prevention centers, but the American Medical Association pretty much summed it all up in 2017 when it said:

“Studies from other countries have shown that supervised injection facilities reduce the number of overdose deaths, reduce transmission rates of infectious disease, and increase the number of individuals initiating treatment for substance use disorders without increasing drug trafficking or crime in the areas where the facilities are located.”

The New England Journal of Medicine published a study on an unsanctioned overdose prevention center operating in the U.S. from 2014 to 2019.

Researchers found, not only did no one die there, no one had to be transferred to an outside medical facility either.

The Department of Health and Human Services’ National Institute on Drug Abuse delivered a Report to Congress on Overdose Prevention Centers and posted that report online on Nov. 9, 2021.

That report found, “Given the amount and quality of the existing data, it may be prudent to consider the American Medical Association’s recommendation of developing and implementing OPC [overdose prevention center] pilot programs in the United States designed, monitored, and evaluated to generate locality-relevant data to inform policymakers on the feasibility and effectiveness of OPCs in reducing harms and health care costs related to IDU [injection drug use].”

After years of success in other countries, the U.S. just got our first two officially sanctioned sites on Nov. 30, 2021 – both in New York City.

The sites are funded by grants and donations, not tax dollars.

Since they opened less than six months ago, staff have intervened in more than 260 overdoses, according to OnPoint NYC, the provider that runs the sites.

“I know, for some, they might be hearing this and thinking this is a little bit outside the box. A little bit not what I’m used to. But we’re really kind of in a desperate situation. Hundreds of people are dying every day, and they don’t need to be,” said Dr. Khary Rigg, an associate professor at the University of South Florida’s Department of Mental Health Law and Policy.

Rhode Island lawmakers decided last year to authorize a two-year pilot program to establish what they’re calling harm reduction centers. The state started accepting applications in February 2022 for licenses to run those centers.

In Philadelphia, a nonprofit called Safehouse has been in a legal fight with the feds since 2019 to open overdose prevention centers there.

In California, lawmakers are considering a bill to legalize a handful of overdose prevention center pilot programs. This bill has been introduced multiple times over the years. Lawmakers even passed it in 2018, but the governor vetoed it.

Denver City Council voted in 2018 to allow a pilot overdose prevention center. But the state hasn’t approved it, so the center hasn’t opened.

The King County Board of Health in Seattle approved a recommendation to create two overdose prevention sites in 2017, but five years later, none have actually opened.

So, why is the U.S. decades behind other countries on this strategy?

Rigg said Americans still have an old-school perception of people who use drugs.

“People who use drugs are bad and we need to get these people out of our society, lock them up for long periods of time – and that was our approach,” said Rigg. “Addiction was a moral failing. It was a criminal justice problem. But now we have a lot more science around addiction and we know that it is, in fact, a health care problem.”

Will Atkinson, executive director of the Recovery Epicenter Foundation in Pinellas and Pasco Counties, says no one is talking about bringing overdose prevention centers to Florida.

He says overdose prevention centers don’t fit the Sunshine State’s desired image.

“We have the third-largest recovery community in the United States at the moment, just here in Tampa Bay,” Atkinson said. “The more that we’ve focused on tourism and the more we’ve presented ourselves as a retirement community, the less we’ve been interested in addressing substance use disorders, mental health disorders, homelessness, other public safety issues – because that might be unattractive to those who would seek to live here.”

“We have to do something different,” said Tim Santamour, director of outreach for the Florida Harm Reduction Collective, which is based in St. Pete.

Santamour said he doesn’t expect to see overdose prevention centers in Florida anytime soon.

“For Florida, I think it’s a way off. Florida is only now starting to implement harm reduction programs, implement syringe services programs. There are only five of them in the state,” he said.

Syringe Exchanges

Syringe exchange programs

Syringe exchange programs are becoming more common in Florida.

According to Florida Department of Children and Families’ Overdose Prevention Coordinator Jennifer Williams, five counties have operational syringe exchange programs: Broward, Hillsborough, Miami-Dade, Orange, and Palm Beach.

Williams said Pinellas County plans to open a syringe exchange program this summer.

She said Alachua, Leon, and Manatee Counties also have potential syringe exchange programs in the works.

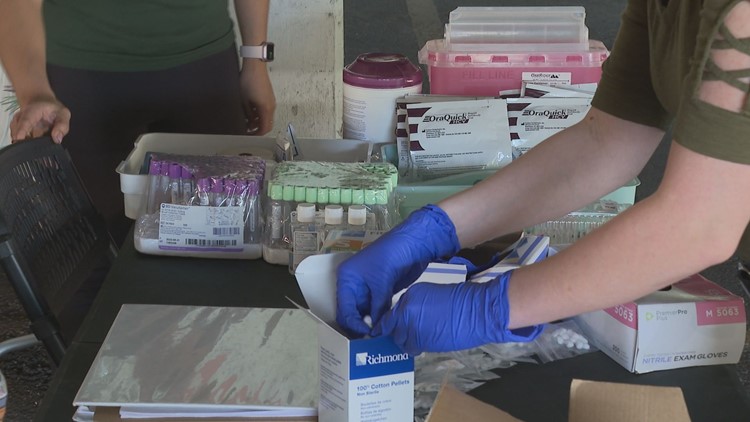

IDEA Exchange runs two syringe exchange sites in Hillsborough County, one in the University Square Mall parking garage and one in Ybor City.

“In the beginning, it was, you know, 10 or 15 was a busy day [at the mall parking garage site]. And then 30 or 40 was a busy day. And now 75 people – usually 60-75 people every Monday and Friday. And at our Ybor site, we went from 2-3 people a shift and now we’re cresting 50 people a shift,” said Heather Henderson, Ph.D., director of social medicine at Tampa General Hospital’s Division of Emergency Medicine.

Not only can clients swap their used needles for clean ones, they can also connect to healthcare and recovery services.

“We have cotton, hepatitis C information. We have the syringes in multiple sizes. We have sharps containers, which are really important. We give each participant a sharps container to safely dispose of their used syringes…We do HIV and Hepatitis C testing,” Henderson said.

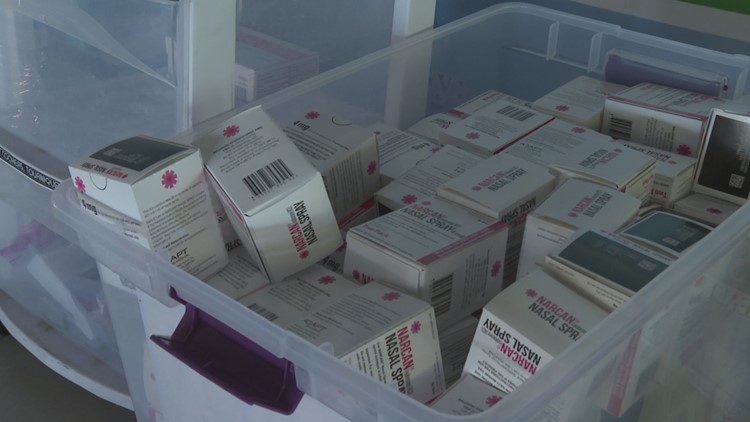

“And, of course, we also distribute quite a bit of Narcan, which is what prevents overdoses and reverses overdoses when they happen,” said Dr. Jason Wilson, associate medical director of Tampa General Hospital’s Emergency Department.

Tampa IDEA Exchange doesn’t get any tax dollars to run these sites. They’re funded by grants and donations.

“You’ve got to be alive to be able to get care. And we’ve got to keep you alive and keep you medically safe to be able to help you make it through this phase of the addiction,” said Dr. Wilson.

Wilson said about 700 people have gotten services at the syringe exchanges in Hillsborough County since they opened in January 2021.