WASHINGTON (USA TODAY) — The United States is in a perpetual state of national emergency.

Thirty separate emergencies, in fact.

An emergency declared by President Jimmy Carter on the 10th day of the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979 remains in effect almost 35 years later.

A post-9/11 state of national emergency declared by President George W. Bush — and renewed six times by President Obama — forms the legal basis for much of the war on terror.

Tuesday, President Barack Obama informed Congress he was extending another Bush-era emergency for another year, saying "widespread violence and atrocities" in the Democratic Republic of Congo "pose an unusual and extraordinary threat to the foreign policy of the United States."

Those emergencies, declared by the president by proclamation or executive order, give the president extraordinary powers — to seize property, call up the National Guard and hire and fire military officers at will.

"What the National Emergencies Act does is like a toggle switch, and when the president flips it, he gets new powers. It's like a magic wand. and there are very few constraints about how he turns it on," said Kim Lane Scheppele, a professor at Princeton University.

If invoked during a public health emergency, a presidential emergency declaration could allow hospitals more flexibility to treat Ebola cases. The Obama administration has said declaring a national emergency for Ebola is unnecessary.

In his six years in office, President Obama has declared nine emergencies, allowed one to expire and extended 22 emergencies enacted by his predecessors.

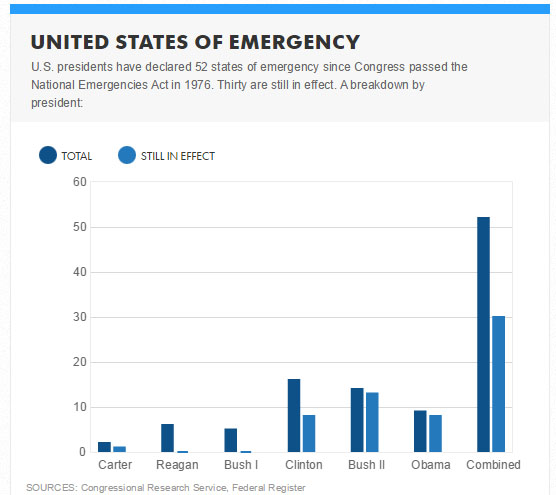

Since 1976, when Congress passed the National Emergencies Act, presidents have declared at least 53 states of emergency — not counting disaster declarations for events such as tornadoes and floods, according to a USA TODAY review of presidential documents. Most of those emergencies remain in effect.

Even as Congress has delegated emergency powers to the president, it has provided almost no oversight. The 1976 law requires each house of Congress to meet within six months of an emergency to vote it up or down. That's never happened.

![635496023102820274-Chart2 [ID=17746617]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/50117b4bfe181f32492ec4d414638d7c08e560e6/r=500x400/local/-/media/WTSP/promo/2014/10/22/635496023102820274-Chart2.jpg)

Instead, many emergencies linger for years or even decades.

Last week, Obama renewed a state of national emergency declared in 1995 to deal with Colombia drug trafficking, saying drug lords "continue to pose an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy and economy of the United States and to cause an extreme level of violence, corruption and harm in the United States and abroad."

In May, President Obama rescinded a Bush-era executive order that protected Iraqi oil interests and their contractors from legal liability. Even as he did so, he left the state of emergency declared in that executive order intact — because at least two other executive orders rely on it.

Invoking those emergencies can give presidents broad and virtually unchecked powers. In an article published last year in the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, attorney Patrick Thronson identified 160 laws giving the president emergency powers, including the authority to:

• Reshape the military, putting members of the armed forces under foreign command, conscripting veterans, overturning sentences issued by courts-martial and taking over weather satellites for military use.

• Suspend environmental laws, including a law forbidding the dumping of toxic and infectious medical waste at sea.

• Bypass federal contracting laws, allowing the government to buy and sell property without competitive bidding.

• Allow unlimited secret patents for Army, Navy and Air Force scientists.

All these provisions come from laws passed by Congress, giving the president the power to invoke them with the stroke of a pen. "A lot of laws are passed like that. So if a president is hunting around for additional authority, declaring an emergency is pretty easy," Scheppele said.

In 2009, Obama declared a state of national emergency for the H1N1 swine flu pandemic. That emergency, which quietly expired a year later, allowed for waivers of some Medicare and Medicaid regulations — for example, permitting hospitals to screen or treat an infectious illness off-site — and to waive medical privacy laws.

Unlike the Ebola crisis, the swine flu had hospitalized 20,000 people and killed 1,000 when Obama declared an emergency.

At a congressional hearing last week, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Tom Frieden said another emergency power — the ability to waive procurement regulations — may be helpful in responding to Ebola.

The White House said an Ebola emergency isn't necessary. "I'm not aware of any consideration that currently is underway (for) any sort of national medical emergency," spokesman Josh Earnest said last week. "I wouldn't rule it out, but frankly ... that's not something that we're actively considering right now."

Presidential emergency powers are hardly new. The Militia Acts of 1792 gave the president the authority to take over state militias to put down an insurrection, which is what President George Washington did two years later during the Whiskey Rebellion. President Abraham Lincoln commandeered ships, raised armies and suspended habeas corpus — all without approval from Congress.

President Franklin Roosevelt declared a state of emergency in 1933 to prevent a run on banks, and President Harry Truman declared one in 1950 at the beginning of the Korean War. After President Richard Nixon declared two states of emergency in 17 months, Congress became alarmed by four simultaneous states of emergency.

It passed the National Emergencies Act by an overwhelming majority, requiring the president to cite a legal basis for the emergency and say which emergency powers he would exercise. All emergencies would expire after one year if not renewed by the president.

Three days after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, President Bush issued Proclamation 7463. It allowed him to call up the National Guard and appoint and fire military officers under the rank of lieutenant general.

That proclamation has been renewed every year since 2001, including by Obama last month.

As of Sept. 30, about 25,700 guard and reserve troops remain involuntarily called up to federal service on the authority of Bush's proclamation, the Pentagon says. Canceling the state of emergency would allow them to go home.

Eight generals and admirals have been appointed to their positions despite laws limiting the number of general officers in each service. That's because the state of emergency allows the president to bypass the law and appoint an unlimited number of one- and two-star generals.

Those numbers are down significantly from their peaks over the past decade. There were 202,750 guard and reserves called up involuntarily in 2003. In 2009, the military had 89 more generals and admirals than Congress allowed for in a non-emergency situation.

The Department of Defense is conducting a review of how it would meet staffing needs if the president fails to renew the state of emergency, said Navy Lt. Cmdr. Nate Christensen, a Pentagon spokesman. That review has been going on quietly for years, and the emergency has been extended each time.

Bush's Proclamation 7463 provides much of the legal underpinning for the war on terror. Bush cited that state of emergency, for example, in his military order allowing the detention of al-Qaeda combatants at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and their trial by military commission.

The post-9/11 emergency declaration is in its 13th year. Eleven emergencies are even older.

OLDEST EMERGENCY

The oldest operational emergency was issued by President Carter in 1979. For Mohamad Nazemzadeh, that state of emergency isn't an academic debate. He's on trial because of it and could get up to 20 years in prison if convicted.

Nazemzadeh, an Iranian-born Ph.D. biochemical engineer, was a research fellow at the University of Michigan where he did research on new radiation therapies to cure cancer and epilepsy. In 2011, he attempted to broker the sale of a $21,400 refurbished MRI coil to an Iranian hospital.

That's illegal under a string of executive orders dating back to the Carter administration. Carter, invoking his emergency powers under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, imposed an embargo on trade with Iran in 1979. That emergency has been renewed every year since.

In its current form, the executive order has an exception for medicine — but not medical equipment.

In 2010, Congress passed the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions Accountability and Divestiture Act. The law tightened sanctions against Iran but included broader exceptions, including for medical equipment such as the MRI coil.

Nazemzadeh's lawyer, Shereen Charlick, argued that Congress delegated the emergency powers to the president and intended to take part of them back with the 2010 law.

"The congressional exemptions trump the executive order. Since Congress is the lawmaking body and gave the president the emergency powers in the first place, it can remove the authority it delegated to the president. That's my argument," Charlick said. "I did not prevail on that argument. I still think I'm completely right."

Judge James Lorenz rejected that argument. "It is undisputed that the plain language of IEEPA vests authority to the president to declare an emergency and implement economic sanctions," he said in his ruling in January. Even though Congress made it legal to send medical equipment, the president can use his emergency powers under the old law to require a license, the judge ruled.

Nazemzadeh didn't have a license. Such licenses are routine but expensive.

"If you look at the history of IEEPA, it was to give the president extra powers in times of emergency. It wasn't intended to permanently expand the powers of the executive branch. It's all on fairly shaky ground," said Clif Burns, a Washington sanctions lawyer.

The president uses that emergency power because it's the only tool he has to enforce sanctions. Congress has twice allowed the Export Administration Act to lapse — first from 1994 to 2000 and again since 2001 — because of a dispute over anti-boycott provisions involving Israel.

"The president, as well as his predecessors, have declared a number of national emergencies in the context of IEEPA in order to impose economic sanctions, including with respect to the situations in Iran, Syria and in order to address terrorism and proliferation concerns," said Ned Price, a spokesman for the National Security Council. He declined to discuss the internal deliberations around the declaration or renewal of national emergencies.

OVERTURNING EMERGENCIES

The National Emergencies Act allows Congress to overturn an emergency by a resolution passed by both houses — which could then be vetoed by the president. In 38 years, only one resolution has ever been introduced to cancel an emergency.

After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, President Bush declared a state of emergency allowing him to waive federal wage laws. Contractors rebuilding after the hurricane would not have to abide by the Davis-Bacon Act, which requires workers to be paid the local prevailing wage.

Democrats — and some Republicans from union-friendly states such as Ohio and West Virginia — cried foul. Rep. George Miller, D-Calif., introduced a resolution that would have terminated the emergency. Bush, under pressure from Congress, revoked it himself two months later, and Miller's resolution was moot.

"The history here is so clear. The Congress hasn't done much of anything," said Harold Relyea, who studied national emergencies during a 37-year career at the Congressional Research Service. "Congress has not been the watchdog. It's very toothless, and the partisanship hasn't particularly helped."

If anything, Congress may be inclined to give the president additional emergency powers. Legislation pending in Congress would allow the president to invoke an emergency to waive liability for health care providers and to sanction banks that do business with Hezbollah.

Scheppele, the Princeton professor, said emergencies have become so routine that they are "declared and undeclared often without a single headline."

"If we had to break the glass and flip the switch in order to do it ... it would be helpful for the alarm to go off at least. It's a sign that normal law isn't set up right," she said. "States of emergency always bypass something else. So what we need to look at is what's being bypassed, and should that be fixed."