A team of scientists led by the University of South Florida College of Marine Science said it has discovered a giant seaweed bloom that isn't going away anytime soon.

Researchers say the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (GASB) is a belt of brown macroalgae that stretches from the west coast of Africa to the Gulf of Mexico, hitting Florida's coasts.

Last year, more than 20 million tons of this seaweed floated at the surface of the water and "wreaked havoc on shorelines lining the tropical Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and east coast of Florida."

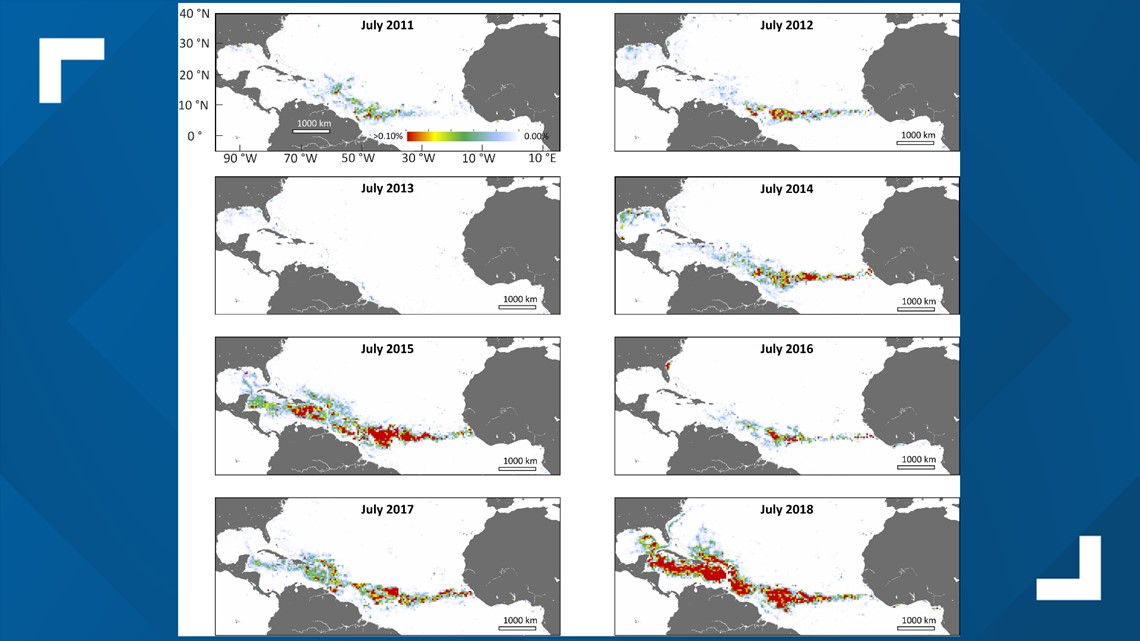

The findings, published in the "Science" journal, said this bloom is the largest in the world. Researchers say these massive mats of seaweed have been seen on satellite imagery since 2011 and have increased in density since then to form the huge belt of algae.

The sargassum seaweed comes from the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic Ocean. USF scientists said this type of seaweed usually flares up in the summer months. The worst blooms usually occur in July and August.

Researchers said the massive seaweed belt forms "seasonally in response to two key nutrient inputs: one human-derived, and one natural." While the seaweed isn't dangerous to humans, it does have a foul odor that can bother people with respiratory issues.

Dr. Mengqiu Wang, a postdoctoral scholar at USF and the lead author of the study, said the sargassum seaweed is healthy for the ocean.

"In the open ocean, Sargassum provides great ecological values, serving as a habitat and refuge for various marine animals," Wang said. "I often saw fish and dolphins around these floating mats."

However, too much of this seaweed can make it hard for some marine animals to breathe. Researchers said when the algae die and sink to the bottom of the ocean, large quantities of it can smother coral and seagrass.

On the beach, piles of rotten sargassum release hydrogen sulfide gas and smell like rotten eggs.

Researchers say it's possible the seaweed blooms grow to such massive proportions because of nutrient runoff, like what is seen in the Amazon River discharge from deforestation and fertilizer use.

"There's a high chance we're still going to see a lot of them in future years," Wang said to WUSF. "So people should find more strategies to handle this problem, and understand the impacts to the ecosystem and to humans as well."

The study was funded by NASA's Earth Science Division, NOAA RESTORE Science Program, the JPSS/NOAA Cal/Val project, the National Science Foundation and by a William and Elsie Knight Endowed Fellowship.

What other people are reading right now:

- Gulf of Mexico disturbance has 80-percent chance of developing, likely to move west

- He called police on black women at swimming pool. Now he’s facing criminal charges

- 16-foot Burmese python found nesting under home in the Florida Everglades

- Man says he was kicked off Busch Gardens ride because he looked too old

- Flesh-eating bacteria suspected in Florida woman

►Make it easy to keep up-to-date with more stories like this. Download the 10News app now.

Have a news tip? Email desk@wtsp.com, or visit our Facebook page or Twitter feed.