FLORIDA, USA — Janos “John” Lutz was 19 when he enlisted in the Marine Corps out of high school, aiming to do his part for his country in the aftermath of the 911 terrorist attacks.

As he hoped, he was deployed to the front lines in Iraq.

Janine Lutz recalls the first time that her son called her from the war zone. He was solemn as he told her what he had seen that day — a car bomb explosion.

“We were the first to arrive at the scene. Body parts were everywhere,” her boy said, guarded as he recounted some of the details. He said he was OK, that this was all part of his service. He was now a Marine, and this is what Marines do.

But at the end of the call, just before hanging up, he suddenly lowered his voice to barely a whisper, so soft that no one could overhear.

“Be careful what you wish for,” he said under his breath.

It was the first crack in his voice she had heard since he joined the military, a chilling reminder of just how real her son’s wish had become.

But as brutal as his time in Iraq was, it was nothing compared to his next assignment in Afghanistan, where he saw combat in one of the largest military offensives of the war. It was during that operation, in July 2009, that his best friend, Lance Cpl. Charles Sharp, was killed. Lutz and his fellow Marines of Echo Company’s second platoon dragged Sharp’s body, hoping to get him to the medical chopper, but Sharp bled to death in their hands before they could get him aid. Lutz saw far more carnage, which his mother would learn about only later from some of the Marines with whom her son served.

When Lutz returned to the States a year later, he was tormented by nightmares and the pain from injuries he suffered in a battlefield explosion. At Camp Lejeune, N.C., he was prescribed an assortment of drugs. By the time he returned home to Davie, Florida, he had tried to kill himself — and he was addicted to anti-anxiety medication.

He tried to wean himself off the drugs, and for a brief time, it appeared he was on the road to recovery. But 18 months later, in January 2013, he overdosed on morphine and a powerful sedative, leaving a note on his bedroom door that said “Do not resuscitate.”

He was 24.

About 17 veterans a day commit suicide in the United States. In Florida, 550 veterans died by suicide in 2019, the most recent statistic available from the Florida Department of Veteran Affairs.

For Janine Lutz, the answer lies in veterans connecting with other veterans in their local community.

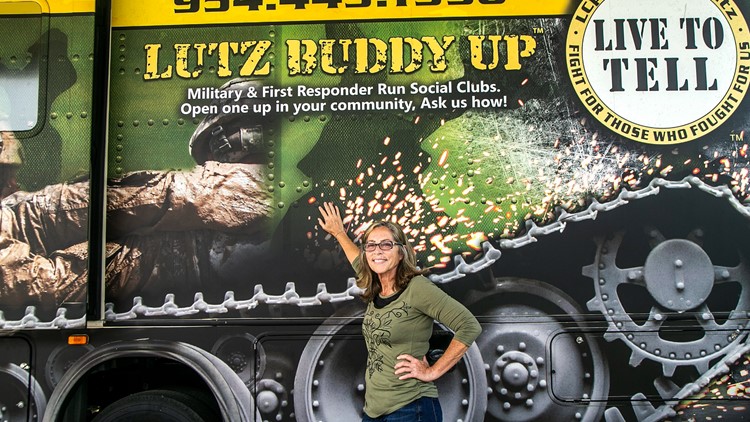

She founded the Cpl. Janos V. Lutz Live to Tell Foundation, which offers programs for veterans with PTSD. Each month, she organizes a Broward Chapter meeting of “Buddies Up,” where veterans and first-responders (who also suffer from PTSD) help each other. She has traveled around the country in an RV organizing similar meetings and has also developed an app for veterans to connect with other veterans.

“People think they have an idea what death and destruction looks like, but until you really see it, it’s a whole different game,” she said.

“These veterans, they think that if they reach out they are being weak. No, by you reaching out, you could be saving that person you are reaching out to.”

The U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs has been working to address the suicide crisis among veterans and members of the military since the late 2000s when rates began to rise.

The epidemic has led the VA to try new approaches, and even to reach out to experts around the world to find solutions. Still, many veterans and their families question how the VA treats post-traumatic combat stress syndrome and other war-related injuries.

“When Johnny came home, he was not the same person. War had changed him. I didn’t understand what was happening because he buried all his trauma and anger in a mind-numbing fog of prescribed medication,’’ his mother said.

It wasn’t until after her son died that Janine learned that VA doctors were prescribing her son a cocktail of drugs so common that members of the military community she spoke to had come to call the therapy “Zombie Dope.”

One pill helped him sleep. Another relieved pain. Another pill was for anxiety. Another was for his depression. The VA prescribed benzodiazepines, which his own medical chart indicated he was not to have. One of the withdrawal symptoms of benzodiazepine is suicide ideation.

“It is just criminal the way the VA gives our veterans a pill for every symptom. For them the answer to their problems is a pill — instead of getting to the root of the problem. Let’s process what they went through, the hell they went through on the battlefield, help them process it through other war fighters, not with some psychiatrist who has never seen battle.”

Between 1.9 and 3 million American troops served in Iraq and Afghanistan, and many of them were deployed more than once, according to the Watson Institute at Brown University.

Countless soldiers who returned home from battle suffer from what is known as “invisible war wounds,” or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and traumatic brain injury (TBI). The military has long struggled with how to treat these brain disorders, largely because they are difficult to detect and diagnose. Many soldiers suffer the psychological effects without realizing what is causing their symptoms, which include depression, anxiety and thoughts of suicide.

Studies show that a majority of people with PTSD who use PTSD medication respond well to an anti-depression medication when used properly. The drugs can improve moods, help patients cope with stress and reduce symptoms of PTSD.

But Cole Lyle, a Marine veteran who served in Afghanistan and now heads Mission Roll Call, a veterans advocacy group, said that medication should not be the primary focus of treating veterans. The agency has spent too long on what its doctors and clinicians call “evidence-based” research and treatments that primarily focus on drugs and psychotherapy, he said.

The VA “looks at the suicide problem among vets as a mental health problem, which is a mistake,” said Lyle. “Looking at it through the lens of mental health leaves out all the other factors that led the veteran to get to that point in the first place.”

Lyle knows what desperation is because he contemplated taking his own life.

“In 2014, after returning from the war, I didn’t have a job. I had a lack of purpose. I felt alone,” he said. “It was a low point in my life. But it compelled me to get involved in veteran politics and policy.”

Now Lyle works with federal and state lawmakers lobbying on behalf of veteran issues, including suicide prevention. He traveled across Florida last month speaking to veterans.

In April, VA officials announced plans to designate more than $50 million in grants for suicide prevention programs to community groups and other grass-roots organizations to help veterans.

In 2020, Congress passed a sweeping bipartisan bill aimed at preventing veteran suicides. Since then, funding for suicide prevention programs has steadily increased from $206 million in 2019 to $598 million in 2022.

“The traditional model of medicating veterans is not conducive in making sure their quality of life is sustained and stable,” said U.S. Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, a Broward County Democrat who chairs the House’s Veteran Affairs subcommittee. “We are now focusing on funding for whole health — not just medicine.”

Over the last several years, the state of Florida has also redirected some of its funding into community-based programs that are better able to reach veterans who have PTSD and brain injuries.

“We are getting away from medicines and now we have other therapies,’’ said Steve Murray, spokesman for the Florida Department of Veteran Affairs. “We have hyperbaric oxygen treatment, canine warriors, equine therapy, light-sensitivity therapy. We are now using non-traditional ways of addressing the issue and there’s been some success in that.”

But he and others acknowledge many veterans fail to avail themselves of programs. Military members are often reluctant to seek help, and historically, there has been a distrust of the VA.

“Many veterans I talk to don’t use the VA and have negative perceptions of the VA. There’s no way to counter those perceptions — they try to use the VA but get frustrated by the sheer amount of communications just to schedule an appointment,” Lyle said.

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis recently launched a veterans’ suicide prevention program and has expanded career and training opportunities for members of the military. Among other things, the state has staffed its 211 information hotline with veterans accredited to help other veterans. Every county in the state also has a veteran affairs coordinator, and every VA medical center has a suicide prevention coordinator who conducts outreach.

But the state is vast, and many veterans retire to Florida from other states without registering for VA benefits in Florida.

“My sense is we still have a crisis in the state of Florida. We still don’t know who all the veterans are in Florida. We have to reach them,’’ said Clara Reynolds, CEO and president of the Crisis Center of Tampa, which provides funding for veteran suicide-prevention programs throughout Florida.

“We have some very high pockets of veteran suicide in the state, and we are all trying to work together as a state. No one agency can do it, it takes all of us working together to tackle this together.”

COVID-19 also slowed outreach, though it didn’t stop altogether, said Murray, a retired U.S. Air Force lieutenant colonel who has worked for the state’s veteran affairs office for 16 years. Some therapies are still being offered remotely through telehealth, which has connected veterans in more rural areas of the state to programs, he added.