TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Florida is just full of surprises. Among them, you might be shocked to know that the first-ever known observance of Christmas in the U.S. happened right here in the Sunshine State.

But the event was nothing like the holiday we've come to know today — it actually involved quite a bit of violence.

Archaeological and documentary evidence shows that Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto and his expedition of 600 soldiers, slaves, craftsmen and adventurers observed the holiday while encamped at the Apalachee town of Anhaica. The location is now known today as Florida's capital of Tallahassee.

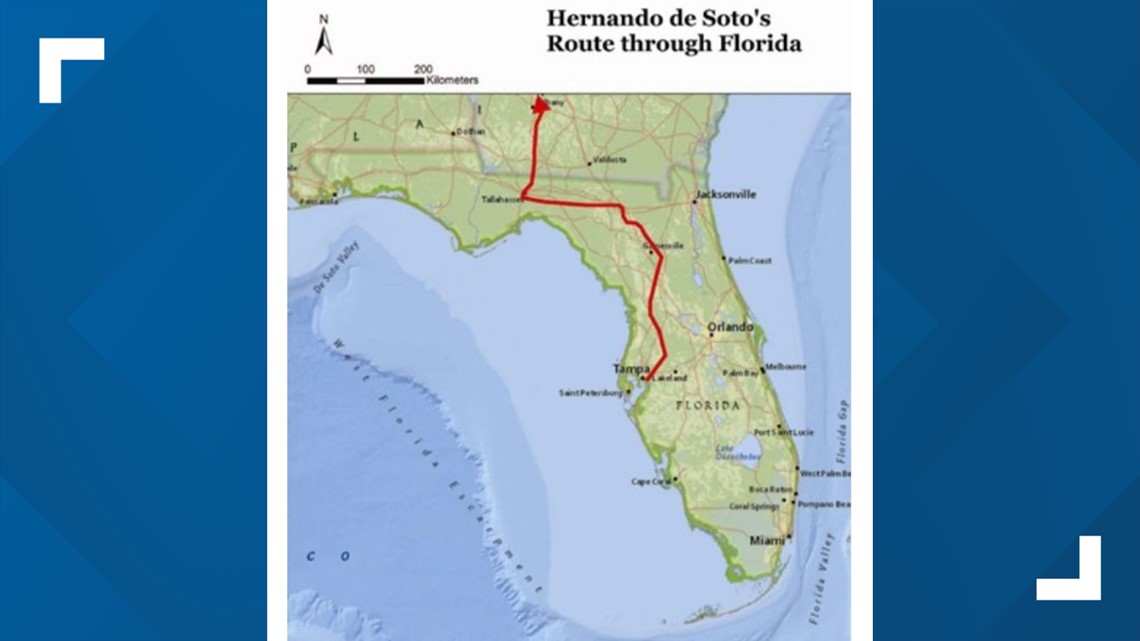

De Soto and his soldiers set out from Cuba in 1539 before landing in the Tampa Bay area to start his quest for precious metals and other resources deemed valuable to Spain.

Their journey led them to northern Florida to Anhaica where state archives show they set up camp due to the fast-approaching winter. The time was believed to be October 1539.

The site is where they would later hold America's first known Christmas and while "documentary evidence is scant," historians say it went a little something like this:

There were no presents, holiday tunes, or building snowmen. Instead, it's believed that a traditional Catholic mass marked the occasion, given the 12 Catholic priests that were included in de Soto's expedition.

A large feast also likely occurred, thanks in part to the immense amount of maize and beans that the Apalachee natives left behind when the Spaniards forced them out.

And while Christmas time is typically associated with peace and joy, this holiday event was was lacking just that.

"At the time, Christmas was a more solemn affair, and it lacked many of the celebrations associated with present-day celebrations," Florida's Division of Historical Resources wrote. "However, because the expedition was under frequent attack by the Apalachee, Soto and his men were likely too busy to participate in many holiday celebrations."

The natives were displaced by de Soto and regularly attacked their troops and hunting parties in response. The State Library and Archives of Florida even reports the Apalachee even attempted "to burn the town down by flinging torches and shooting flaming arrows into it."

De Soto responded with "ruthless tactics" and while historians report the expedition lost 20 members, it's unknown how many Apalachees were killed by Spanish attacks, disease or starvation.

According to historians, de Soto's violence while pushing through the southeastern United States "would forever change the landscape of the region, decimating populations through disease and violence, and disrupting longstanding and powerful Chiefdoms."

In the end, de Soto never established a colony and later died of a fever. Half of his men survived the expedition and are reported to have fled Florida by raft to Mexico.