With 169 days until the general election, states are relaxing shutdown and stay-at-home orders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

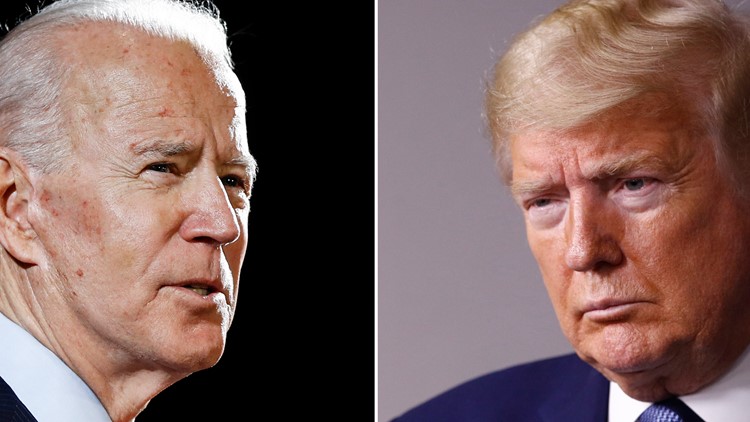

President Donald Trump is traveling more, determined to model the confidence he believes the nation needs to return to normal. Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic nominee, continues a virtual campaign from his Delaware residence, determined to heed public health recommendations he says are the first steps toward a national recovery. Meanwhile, the U.S. coronavirus death toll now exceeds 89,000, and there are more unemployed working-age Americans than at any other point in history.

Biden's advisers have struck a confident tone after other Democrats openly questioned how they're using their early start to the general election. In her most recent conversation with reporters, campaign manager Jen O'Malley Dillon teased at "a much larger Electoral College victory than we would even need to capture the presidency."

Dillon is bullish on Arizona, a state Democrats have won exactly once since Biden was elected to the Senate in 1972. The Trump campaign, meanwhile, distributed a memo claiming the president leads in "the 15 states that could decide" the electoral vote outcome.

Recent polling actually gives Trump plenty to worry about, yet it's difficult not to remember that Hillary Clinton's campaign conspicuously expanded its operation into Arizona, Georgia and other GOP strongholds in 2016. Clinton lost them all — along with the Great Lakes states where she didn't campaign heavily because her aides considered them a "Blue Wall." O'Malley Dillon notes, of course, that she isn't investing in the likes of Arizona at the expense of Wisconsin.

It will become clear in coming months whether Biden is seriously aiming that wide or merely posturing to make Trump spread his ample resources across more states.

And then there is the matter of choosing a Vice President. Kamala Harris and Amy Klobuchar joined Biden for fundraisers. Stacey Abrams appeared with him on MSNBC. Tammy Duckworth headlined virtual events on his behalf. Elizabeth Warren co-signed an op-ed with her former primary rival.

Several high-profile Democrats have floated their preferences — effectively advising Biden through the media (if not also privately). So does any of this matter? Are these events basically preliminary interviews? Does Biden read the chatter? All of the above? Those who've gone through the process before offer one consistent reminder: Once you get past the noise, it's a choice made by one person only — the nominee.

Part of the Biden campaign's public optimism comes from finally getting his fundraising operation on track. In April, Biden and the Democratic National Committee cleared more than $60 million, just shy of what Trump and the Republican National Committee collected. That's a win for a campaign that battled empty pockets in the primary and for a national party that's looked up at its GOP counterparts for years. To be sure, the GOP team said it has more than $250 million on hand, compared with the Democrats' $103 million. But if Biden roughly keeps pace with Trump in new collections, it will at least ease some Democrats' concerns.

Does the next coronavirus package matter on the presidential trail? Capitol Hill Democrats want another coronavirus aid package, with a $3 trillion price tag, including support for state and local governments that have watched their tax receipts evaporate during the COVID-19 shutdown.

For now, public sentiment still appears to favor aggressive government action to prevent a depression, but there's no easy calculation for how that plays out in the presidential campaign, where the two contestants boast murky records and conflicting priorities.

Once a centrist senator who backed a balanced-budget constitutional amendment, Biden has generally endorsed his fellow Democrats' moves for aid. His team sees little political fallout because of skyrocketing unemployment and economic paralysis. His argument: What is government for if not this? But, it's still potentially tricky branding.

Republicans are growing increasingly comfortable drawing a line in the spending sand and casting the opposing party as gluttonous spendthrifts. But Trump doesn't fit neatly. He's not a doctrinaire conservative or budget hawk by any definition, and he wants to boost an economy that just two months ago was his principal argument for a second term. Yet the president, always the eager rhetorical combatant, loves to magnify Republican cries of "SOCIALISM!" against any Democrat.

Trump's latest angle against Biden is "Obamagate," the right wing's chosen label for the revelation that Biden, as vice president, was briefed on the investigation of Gen. Michael Flynn's interaction with Russia before Trump took office. Flynn's "unmasking" — being identified by name after intelligence agencies tagged his communications with foreign agents — is a routine part of national security law enforcement. But Trump frames the case as evidence of an endless effort to undermine an entire presidency — now with Biden as a central player. That clearly animates Trump's political base and makes Biden's base yawn. But are the effects wider?

Somewhat at odds with the whiplash of the first three years of Trump's presidency, Year Four has a dominant, ubiquitous storyline. It's forced the incumbent and his challenger into roles beyond their long-cultivated brands. Trump, whether he likes it or not, is the chief executive of a federal government at the center of a pandemic and resulting economic collapse, the showman now responsible for governing. Biden is the avuncular, back-slapping creature of the Senate restyling himself as a chief executive in the mold of Franklin Roosevelt. The winner in November may well be the figure who wears his new part more comfortably.

___

Catch up on the 2020 election campaign with AP experts on our weekly politics podcast, "Ground Game."