THE VILLAGES, Fla. — Democrats are increasingly concerned that Florida, once the nation's premier swing state, may slip away this fall and beyond as emboldened Republicans capitalize on divisive cultural issues and population shifts in crucial contests for governor and the U.S. Senate.

The anxiety was apparent last week during a golf cart parade of Democrats featuring Senate candidate Val Demings at The Villages, a retirement community just north of the Interstate 4 corridor. It was once a politically mixed part of the state where elections were often decided but now some Democrats now say they feel increasingly isolated.

“I am terrified,” said 77-year-old Sue Sullivan, lamenting the state’s rightward shift. “There are very few Democrats around here.”

In an interview, Demings, a congresswoman and former Orlando police chief challenging Republican Sen. Marco Rubio, conceded that her party’s midterm message isn’t resonating as she had hoped.

“We have to do a better job of telling our stories and clearly demonstrating who’s truly on the side of people who have to go to work every day,” she said.

The frustration is the culmination of nearly a decade of Republican inroads in Florida, where candidates have honed deeply conservative social and economic messages to build something of a coalition that includes rural voters and Latinos, particularly Cuban Americans. Donald Trump's win here in 2016 signaled the evolution after the state twice backed Barack Obama. And while he lost the White House in 2020, Trump carried Florida by more than 3 percentage points, a remarkable margin in a state where elections were regularly decided by less than a percentage point.

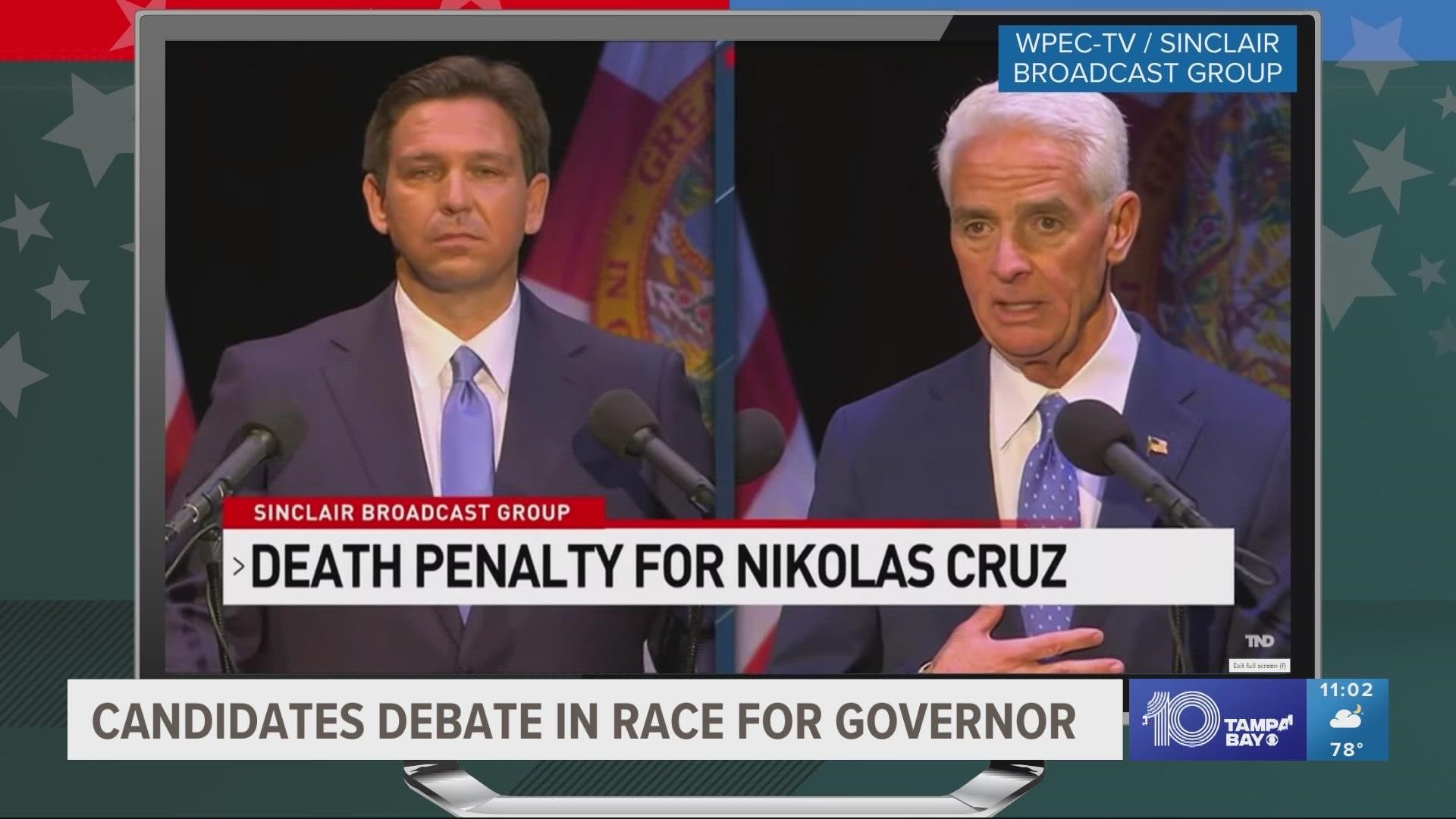

President Joe Biden will visit the state Nov. 1, exactly one week before Election Day, to rally Democrats. Demings said she's had two conversations with the president about campaigning together, but she could not confirm any joint appearances. And Charlie Crist, the Democratic nominee for governor, said he would attend a private fundraiser with Biden on the day of the rally, but he wasn't sure whether they would appear together in public.

“If we could squeeze in a little public airtime, that’d be a wonderful thing I would welcome,” Crist said in an interview.

Still, the GOP is bullish that it can keep notching victories, even in longtime Democratic strongholds. Some Republicans are optimistic the party could carry Miami-Dade County, a once unthinkable prospect that would virtually eliminate the Democrats' path to victory in statewide contests, including presidential elections.

And in southwest Florida’s Lee County, a major Republican stronghold, not even a devastating hurricane appears to have dented the GOP’s momentum. In fact, Republicans and Democrats privately agree that Hurricane Ian, which left more than 100 dead, may have helped Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis broaden his appeal.

But the 44-year-old Republican governor has spent much of his first term focused on sensitive social issues. He's signed new laws banning abortions at 15 weeks of pregnancy with no exceptions for rape or incest, along with blocking critical race theory and LGBTQ issues from many Florida schools. He has also stripped millions of dollars from a major league baseball team that spoke out against gun violence and led efforts to eliminate Disney's special tax status for condemning his so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bill.

On the eve of the hurricane, DeSantis shipped dozens of Venezuelan immigrants from Texas to Martha’s Vineyard to call attention to illegal immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Crist, a former congressman and onetime governor himself, acknowledged some voters “dig” DeSantis’ focus on cultural issues, “but most Floridians are good, decent people.” He noted that at least one Hispanic radio host has compared DeSantis to former Cuban dictator Fidel Castro.

“Customarily, when you come out of a primary, people will move to the middle. He’s clearly not doing that, to say the least,” Crist said of his Republican rival.

But to the horror of many Democrats, DeSantis could become the first Floridian to win a governor’s race by more than 1 point since 2006. That kind of showing might lift Rubio in the U.S. Senate election while helping the GOP win as many as 20 of the state's 28 U.S. House seats.

Should DeSantis win big as expected, his allies believe he would have the political capital to launch a successful presidential campaign in 2024 — whether Trump runs or not.

“It’s shocking and it’s scary,” state Democratic Party Chair Manny Diaz said about DeSantis’ repeated willingness to use the power of his office to attack political rivals, whether individual opponents or iconic corporations like Disney.

DeSantis, who declined an interview request, has found success by bucking the conventional wisdom before.

He beat Democrat Andrew Gillum four years ago by 32,436 votes out of more than 8.2 million cast, a margin so narrow that it required a recount.

But in the four years since then, Republicans have erased a voter registration advantage that Florida Democrats had guarded for decades. When registration closed for the 2018 election, Democrats enjoyed a 263,269-vote advantage. As of Sept. 30, Republicans had a lead of 292,533 voters — a swing of nearly 556,000 registered voters over DeSantis' first term.

“We're no longer a swing state. We're actually annihilating the Democrats,” said Florida GOP Chairman Joe Gruters, a leading DeSantis ally.

And while he says his party has focused on traditional kitchen-table issues, such as gas prices and inflation, Gruters leaned into cultural fights — especially the Florida GOP's opposition to sexual education and LGBTQ issues in elementary schools — that have defined DeSantis' tenure.

“I don't want anyone else teaching my kids about the birds and the bees and gender fluidity issues," Gruters said.

Strategists in both parties believe Florida's political shift is due to multiple factors, but there is general agreement that Republicans have benefited from an influx of new voters since DeSantis emerged as the leader of the GOP resistance to the pandemic-related public health measures.

Every day on average over the year between 2020 and 2021, 667 more people moved into the state than moved away, according to U.S. Census estimates.

Part of the Republican shift can also be attributed to people living in rural areas of north Florida, remnants of the deep South, changing their registration to reflect their voting patterns. Many people registered as Democrats because generations before them did, but the so-called Dixiecrats still voted solidly Republican.

But that alone does not explain the Democrats' challenge this fall.

Democrats are particularly concerned about the trend in Miami-Dade County, home to 1.5 million Hispanics of voting age and a Democratic stronghold for the past 20 years, where the GOP made significant gains in the last presidential election. In two weeks, the region could turn red.

“We have seen so many Hispanics flock to the Republican party here in Miami-Dade County,” Florida Lt. Gov. Jeanette Núñez said at an event with other party leaders last week. “I’m going to make a prediction right now: We are going to win Miami-Dade County come Nov. 8.”

Meanwhile in southwest Florida, thousands of Republican voters are picking up pieces of their shattered homes and vehicles in the wake of Hurricane Ian, which left more than 100 people dead and caused tens of billions of dollars in damage.

Mangled boats and massive chunks of concrete docks still litter the coastline in Fort Myers, the county seat of Lee County, one of the nation's most Republican-leaning counties. Thousands of homes were destroyed and several schools remain closed nearly a month after the Category 4 hurricane made landfall.

Still, Matt Caldwell, the county property appraiser and a member of the state GOP, was confident about his party's political prospects.

“Most of the people, 90% of the people who live in the county are more or less back to life at this point,” he said as he toured a Fort Myers marina covered by twisted metal and crumpled yachts.

Caldwell praised the Republican governor for being a regular presence during cleanup efforts, suggesting that voters across the political spectrum may reward him on Election Day.

DeSantis himself was upbeat as he delivered a storm update not far away in Punta Gorda over the weekend. The governor referred to the coming election, but focused his remarks on relief efforts.

“We’ve had success with bridges and all these other things partially because we have the community rallying together,” DeSantis said. “Everyone’s rowing in the same direction. It makes a difference.”