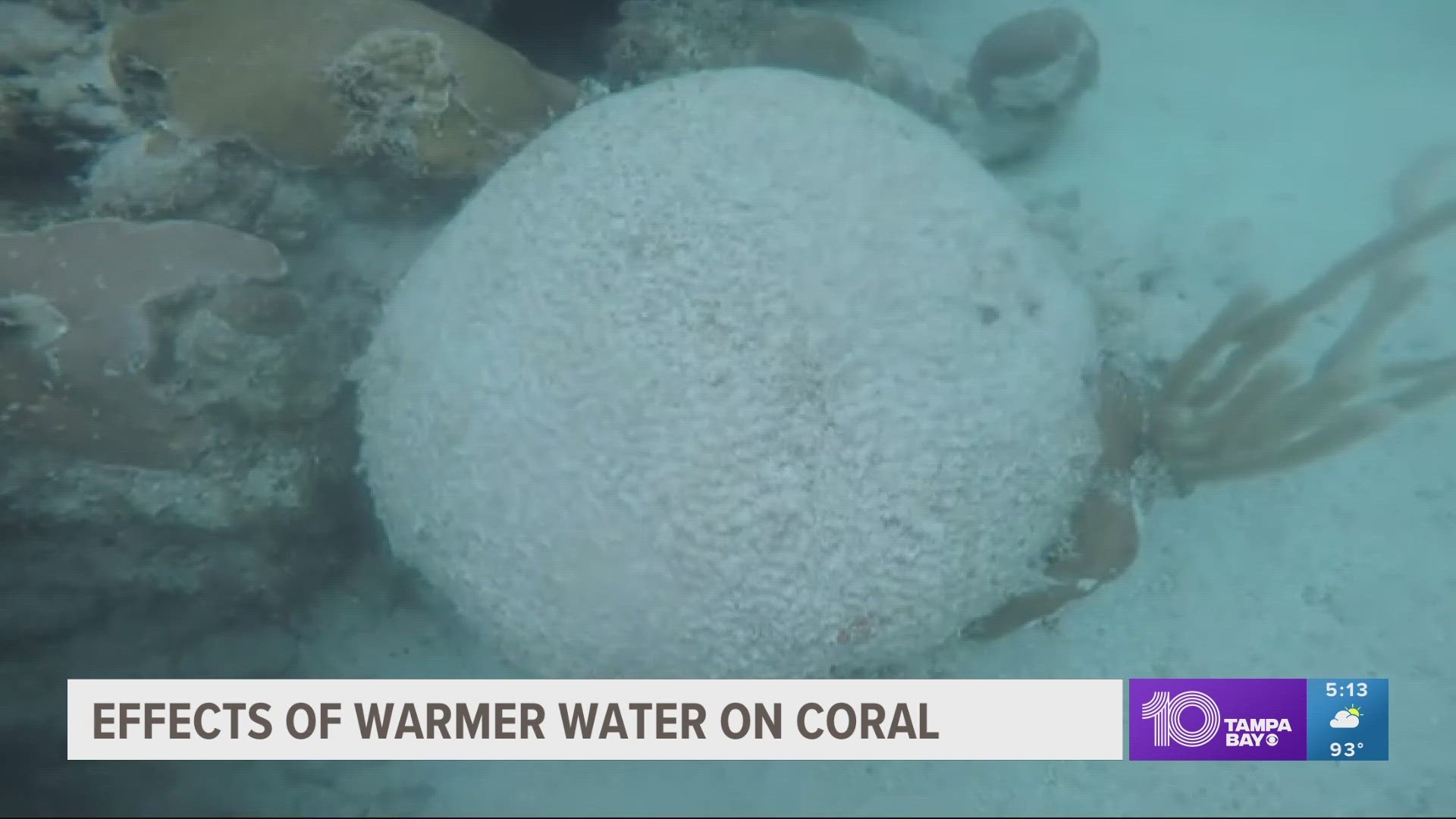

ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. — Florida's oceans are heating up to historically high temperatures leaving coral reefs at risk of turning white and dying off. With coral bleaching expected to continue all through the summer, the University of South Florida's Keys Marine Laboratory is storing thousands of specimens of coral until water temperatures return to normal.

The Keys Marine Laboratory, which is part of the Florida Institute of Oceanography, holds one of the largest temperature-controlled saltwater systems in the Florida Keys with 60 tanks ranging from 40 to 1,000 gallons of water. Partner institutions like The Florida Aquarium and the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission use the KML to study corals and other forms of marine life and to rehabilitate and grow vulnerable species.

The KML is currently housing over 1,500 coral specimens, many of which are rare and endangered species harvested from offshore nurseries and parent colonies, and they have the capacity to store thousands more throughout the summer.

“For years we have been developing the infrastructure capacity to support reef restoration efforts that enable KML to temporarily house corals during emergencies such as this,” Cynthia Lewis, director of KML said.

The corals will be housed in the laboratory's land-based systems for months, with some being rehabilitated and others being used as part of breeding programs.

“Some of the corals held here today will become part of our coral breeding program at The Florida Aquarium and will be given world-class human care for the rest of their lives, producing hundreds of offspring every year," Coral Conservation Program Director Keri O’Neil said. "When the time is right to return those offspring to the reef, they will once again have a short stay at Keys Marine Laboratory before returning to the ocean.”

Coral reefs serve as critical habitats for fish, crabs, turtles and many other forms of marine life. They offer natural protection from storms, waves and erosion that can cause flooding.