TAMPA, Fla. — Amid the breathtaking beauty of Tampa Bay, there is a constant current of change for the Tampa Bay harbor pilots. In an ocean that can turn from peaceful to perilous, the pilots are required to have a calm voice and a steady hand.

“You really do have to know how to work under pressure. You’ve got to be quick on your feet. You’ve got to be on point all the time,” pilot Tevin Freeman said.

At 4 a.m., Freeman and harbor pilot Brett Monthie boarded a small boat and headed to meet two big ships in the pitch-black Gulf of Mexico. Freeman was preparing to board a 700-foot-long petroleum barge carrying 300-thousand barrels. Monthie was meeting A 524-foot tanker carrying molten sulfur. Their job is to safely deliver the ship, crew and contents to Port Tampa Bay.

“I just call us glorified valet drivers,” Freeman joked.

As Monthie meets the tanker, he has to climb from the moving pilot boat to the moving ship. It can be perilous, especially in rough weather.

“We’ve got to be on our game, all the time, in any weather condition,” Monthie explained.

How harbor pilots work with ship captains

Once onboard, Monthie meets with ship captain Brad Walden before taking control.

“He’s navigating, obviously direction. We’re monitoring speed, anticipating traffic movements, upcoming turns and how the vessel’s going to slide into a turn, stay steady on a turn. So, my role is to basically follow what he is doing,” Walden said.

Becoming a harbor pilot requires years of study and intense testing.

“You have to know this port in and out from memory. Depths of different obstructions that can be hazards to navigation, range of tide, different things like that, weather, “ Freeman explained.

While the 21 harbor pilots know Tampa Bay intimately, a majority of the visiting ship captains don’t.

“A lot of new ships come to the port and again, that’s where the relationship with the pilot is just critical,” Walden said.

As the freighter approaches the Skyway Bridge, Monthie stays in the center of the channel. It can be a tight squeeze, with clearance for some ships under two feet. Knowing the tides, currents and wind restrictions is imperative.

“You pretty much have to be in the correct spot all the time,” Deputy Pilot Jeremy Lowe said.

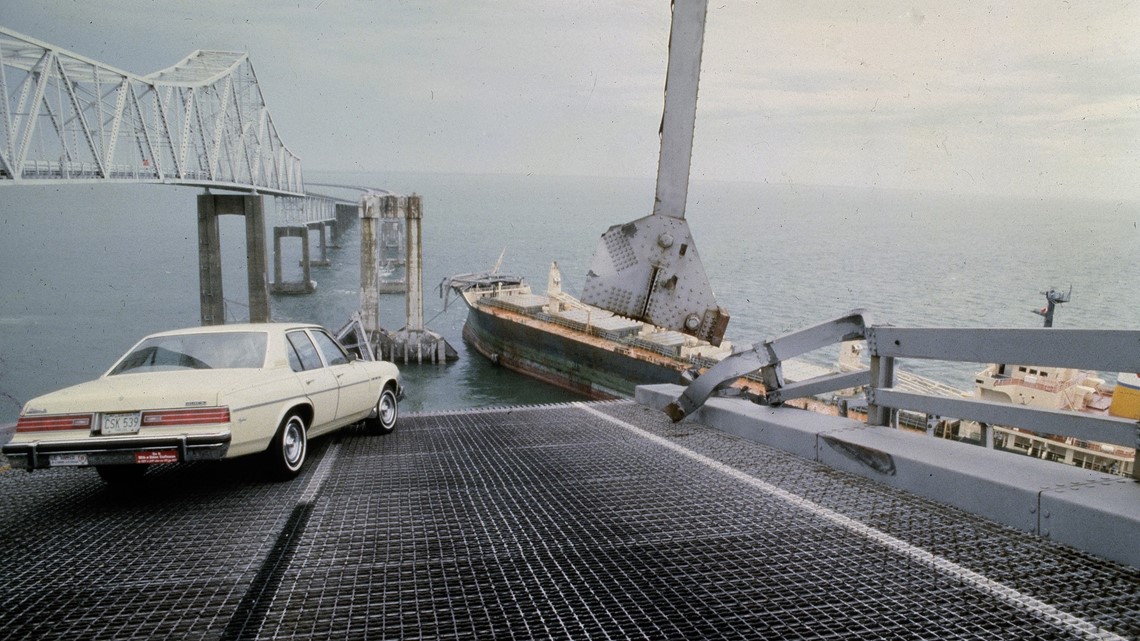

Remembering the 1980 Skyway Bridge collapse

In 1980, a sudden squall sent a freighter into a Skyway Bridge support column, causing it to collapse. 35 people on the highway above plummeted to their deaths. John Lerro was the harbor pilot onboard the “Summit Venture.” While a court ruled he was not responsible for the accident, Lerro told 10 Tampa Bay’s Dave Wagner in 1990 that he could not forgive himself.

“I definitely have had plenty of feelings of unworthiness for screwing up and injuring people I never knew, injuring human beings, killing them,” Lerro said at the time.

The 1980 tragedy is a reminder for every harbor pilot and ship captain as they travel under the Skyway Bridge.

“It’s something everybody knows about and thinks about and helps make judgment calls based off the weather conditions and operating,” Walden said.

Navigating 1,000-foot ships

During hurricanes Helene and Milton, many of the navigational aids used by the pilots were damaged or destroyed. Some buoys are still unlit. The pilot station on Egmont Key is pretty much a total loss. The dock, boat house, spare parts and electronic equipment are all destroyed.

Even with high-tech equipment, it is often the eyes of the pilots that spot potential problems. Pleasure boats around Beer Can Island, planes flying in and out of Peter O. Knight Airport — even rowing teams are obstacles to a safe journey.

“A lot of times, people are just totally unaware, I think, of the speed, the size and what’s at stake if something goes wrong. It’s not going to stop on its own in less than a mile, at least a mile if not longer,” Monthie said.

The channel entering Port Tampa Bay is narrow and often crowded. Some ships are more than a thousand feet long. The tallest building in downtown Tampa is about half that size. It is like trying to park a thousand-foot-long vehicle at Raymond James Stadium on game day.

“And luckily technology’s improved, right? But the ships have also doubled in size, tripled in size,” Monthie added.

Onboard with Tampa Bay harbor pilots

After delivering their ships safely to Port Tampa Bay, their next trip is just hours away. The pilots work 24-hour shifts, two weeks on and two weeks off. Monthie was raised far from the ocean. But after attending the United States Merchant Marine Academy, he was drawn to the water.

“I grew up in Kentucky. So, this is all foreign to me," Monthie said.

Tevin Freeman was born in the British Virgin Islands.

“Six years old, I took my first cruise, told my dad when I walked on, I wanted to be a ship captain and here I am,” Freeman said.

From container ships to cruise ships to super yachts belonging to billionaires, the vessels vary, the conditions change, but the core mission of the Tampa Bay pilots remains the same.

“Basic principles are people, assets, environment. They’re always looking ahead, planning for the next move. It’s definitely chess, not checkers,” Captain Walden said.