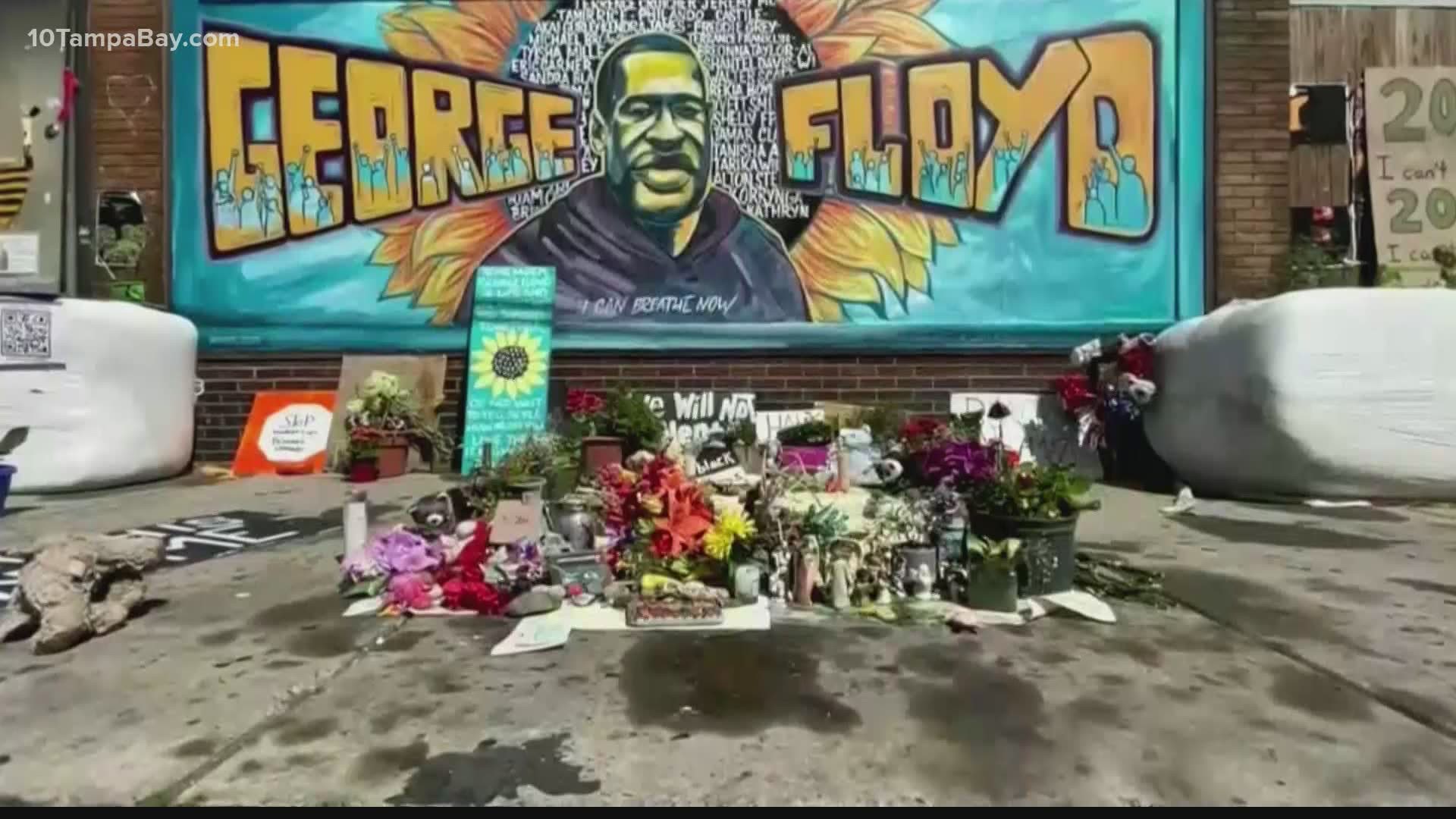

TAMPA, Fla. — One year ago, George Floyd was murdered.

Then-Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on the 46-year-old's neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds, as Floyd repeatedly said "I can't breathe."

A jury convicted Chauvin of murder and manslaughter. Three other ex-officers await trial on charges of aiding and abetting him.

The May 25, 2020, murder of a Black father by a white police officer led to racial justice protests as far away as Sydney, Australia, and as close to home as Tampa.

President Joe Biden is meeting with Floyd's family Tuesday at the White House. The day was the deadline the 46th president had set for Congress to pass the stalled George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

The legislation passed the U.S. House again this year but has not yet been considered in the Senate. If passed and signed into law, it would increase accountability for police misconduct, limit qualified immunity, and restrict the use of no-knock warrants and chokeholds. The bill would also form a national registry for police misconduct, increase training for officers, and direct the Department of Justice to create uniform accreditation standards for law enforcement agencies.

While the legislation sits in limbo, what has changed since George Floyd's murder?

1. Confederate symbols were removed at a greater pace

Nearly 170 Confederate symbols that had been on public display in the United States were taken down, relocated or renamed in 2020, according to the nonprofit Southern Poverty Law Center.

All but one of those 168 symbols were removed after George Floyd's death. Ninety-four of those symbols were Confederate monuments – meaning more monuments were eliminated last year than in 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019 combined.

Seventy-one of the symbols were removed in Virginia alone.

The Alabama-based watchdog group's February report revealed more than 2,100 Confederate symbols are still publicly present across the country.

"This encompasses government buildings, Confederate monuments and statues, plaques, markers, schools, parks, counties, cities, military property and streets and highways named after anyone associated with the Confederacy," the SPLC wrote.

A total of 704 of those symbols are monuments.

2. Neck restraints limited, banned in some places

Within a month of George Floyd's murder, Colorado lawmakers banned chokeholds as part of a broader police reform effort that overrode more limited restrictions enacted four years prior. More states joined in, with legislators prohibiting or seriously restricting officers' use of neck restraints and chokeholds.

In total, at least 17 states – including Minnesota – have enacted laws to restrict the practice, according to data provided to The Associated Press by the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Before Floyd was killed, just two states, Tennessee and Illinois, had bans on police hold techniques that restrict the airway or blood flow to the brain when pressure is applied to the neck.

In the Tampa Bay area, some police agencies took steps to change policies themselves. The Temple Terrace Police Department and the Sarasota Police Department suspended the use of neck restraints following Floyd's murder.

3. Police officers leave their jobs

In the year since Floyd's death, Minneapolis City Council voted unanimously to spend $6.4 million to recruit more police officers.

You may wonder – amid "defund the police" messaging from some protesters, why is that money being spent that way? It's because, by February, the department only had 638 officers available to work, which is about 200 fewer than normal.

As the Associated Press reported, an "unprecedented" number of officers either quit or took extended medical leave after the murder of George Floyd and subsequent unrest that included a police precinct being set on fire.

And the departures of officers were not limited to the Minneapolis area. In Seattle, CBS News reports 260 officers – or nearly 20 percent of the force – have left in the past year and a half.

CBS, citing a social justice group, recently reported more than $840 million had been cut from police budgets nationwide in 2020.

4. Corporate America took a stand

Speaking with Politico, Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a senior associate dean at the Yale School of Management, recently described how the outrage over George Floyd's murder served as a wake-up call for U.S. corporations.

Sonnenfeld explained how Merck CEO Ken Frazier, one of four Black CEOs on the Fortune 500 list, helped unite several dozen CEOs and gather more than $100 million to create the OneTen workforce program – an effort to secure 100 million good jobs for Black workers who don't have college degrees.

As Politico reports, Goldman Sachs launched a One Million Black Women initiative to make $10 billion worth of direct capital investments and offer $100 million in gifts to combat racial and gender bias that has adversely affected Black women in particular. Target's CEO vowed to put $2 billion into Black-owned businesses, and Walmart's CEO invested $100 million into community-based economic development efforts, the outlet added.

The actions of corporate America are consistent with evolving viewpoints about businesses' responsibilities to address issues of race. A newly-released survey found two-thirds of Americans want their companies to publicly speak out against racial injustice, according to USA Today. A majority of respondents said they'd hold their bosses accountable if their employers didn't take a stand.

Adidas promised to fill at least 30 percent of open positions in the U.S. with candidates who are Black or Latinx.

Amazon recently extended its ban on police use of its facial-recognition technology.

RELATED: 'Something changed here' | Family, community remember George Floyd in Minneapolis rally and march

5. 'Systemic racism' conversations become more widespread

Journalist Erin Aubry Kaplan recently told Politico how the murder of George Floyd sent the term "systemic racism" into the mainstream. Previously used mostly among academics and activists, major publications began using the terminology in their reporting.

In fact, as Kaplan points out, President Biden broke new ground when he used the term in his inaugural speech after also bringing the phrase into his convention and election night addresses.

"Even many of those who still think the term goes too far are acknowledging that America’s ugly past has finally caught up to the present, and the present is reshaping our political future," Kaplan wrote in Politico. "This tectonic shift in public sentiment about race reminds me of what a friend and fellow journalist always told me when I despaired about the snail’s pace of social progress in America: The status quo is the status quo, until it changes. It is possible for big change to happen overnight."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

- 3-year-old accidentally shoots little sister, Polk County Sheriff says

- FWC tracking bear spotted roaming through Pasco County

- Gov. DeSantis announces 'Freedom Week' sales tax holiday

- Sisters reunite in Tampa after spending a half-century apart

- New 'Project Opioid' aims to decrease opioid deaths in Tampa Bay by 2025

- Florida still short of Biden's 70-percent vaccination goal

►Breaking news and weather alerts: Get the free 10 Tampa Bay app

►Stay In the Know! Sign up now for the Brightside Blend Newsletter