RIVERVIEW, Fla. — In a sea of sprawling subdivisions in Riverview, you will find a part of Hillsborough County history that is buried. Samford Cemetery is overgrown and surrounded by subdivisions. Among the markers, there is a small gravestone for a giant of a man who left a towering mark on the midway.

“There are probably a lot of forgotten gravesites in this area,” carnival historian David “Doc” Rivera said.

In a 54,000-square-foot building in Riverview, Rivera has curated the history of traveling shows with the Showmen's Museum.

“Carnivals, circuses, Wild West shows, patent medicine shows. We like to say, 'anything having to do with a tented world,'” Rivera said.

The museum features a dizzying array of carnival rides, from a 1903 Conderman Ferris Wheel to a Tilt-A-Whirl to a 1950 Alan Herschell American Beauty carousel.

“At one time, America had over 2,000 carousels turning in this country. To me, one of the worst travesties is the practice of dismantling these carousels today and selling them for the pieces because their intrinsic value has become so great,” Rivera said.

All of the artifacts have been donated, from America’s oldest cotton candy machine to the remains of “Daisy May,” the two-nosed cow, to a top hat worn by Apache leader Geronimo.

“Most of this stuff is irreplaceable. It’s one of a kind,” Rivera said.

Showmen's Museum preserves Tampa Bay area's carnival history

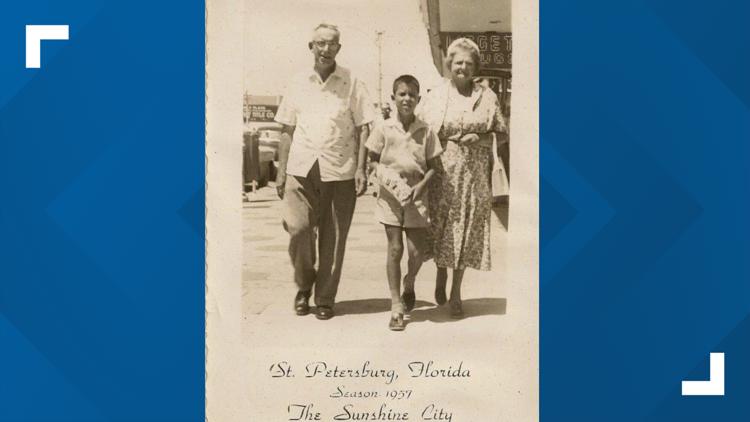

One hundred years ago, Gibsonton became the carnival capital of America. It was called “Gibtown” and instilled fear among some people.

“People used to say, ‘Oh, don’t go to Gibtown after dark. Those carnival people will steal your children’ and we perpetuated the myth because we didn’t want them down here anyway, you know?” Rivera said.

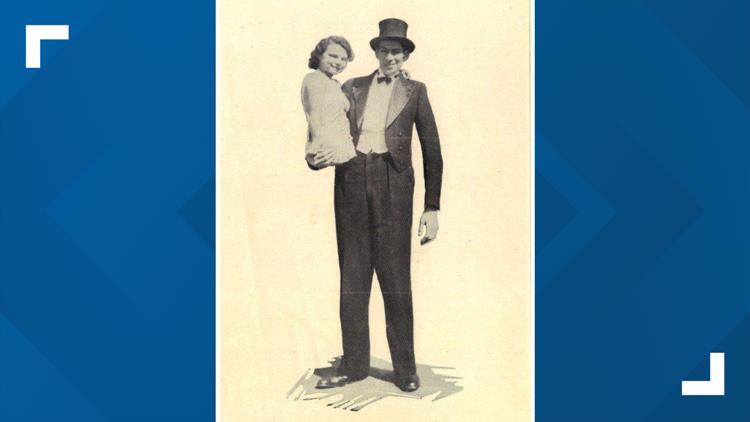

Among those who lived in Gibsonton were sideshow performers. Al and Jeanie Tomaini were billed as “The World’s Strangest Couple.” Al was advertised as being 8’ 4” tall. Jeanie stood just 2 ½ feet.

“This was an area where people of any stripe could come. At one time there were 138 ‘human oddities’ in this town. They also found a home here where they could live amongst each other and not be ostracized by the outlying communities,” Rivera said.

Decades before he curated the Showmen’s Museum, Rivera also found a home in the carnival.

“I had no parents. My grandparents raised me. When I got to be 12-years-old, my grandparents, one of them expired, and they weren’t able to provide a home for me anymore. So, at 14 when the carnival came to town [and] set up on the streets of Laporte, when it tore down, I went with ‘em,” Rivera said.

Through the museum, the show goes on for Rivera. “I’ve done everything in this business. I’ve worked concessions. I even owned a carnival at one time which I equate to the second stage of insanity.”

Today, the insanity and controversy of the carnival industry are on full display at the Showmen’s Museum. One display shows monkeys riding gasoline-powered cars.

“Real monkeys,” Rivera said.

From minstrel shows to automobiles jumping city buses, the museum takes visitors to a different era.

“This is the only carnival and traveling show museum in the world. It was fascinating. As you might imagine, this business attracts characters and I love characters,” Rivera said.

In Samford Cemetery, you will find the gravesites of sideshow performers Al and Jeanie Tomaini. Their markers are surrounded by new housing developments. Rivera is committed to keeping their memory and the history of the tented world alive.

“In just a decade or two, this area just became inundated with people from all over who do not care about this history and don’t even know about it," Rivera said. "Keeping the history of this business alive is vastly important to the generations that will come behind us. You cannot separate the history of America from the history of the traveling shows.”