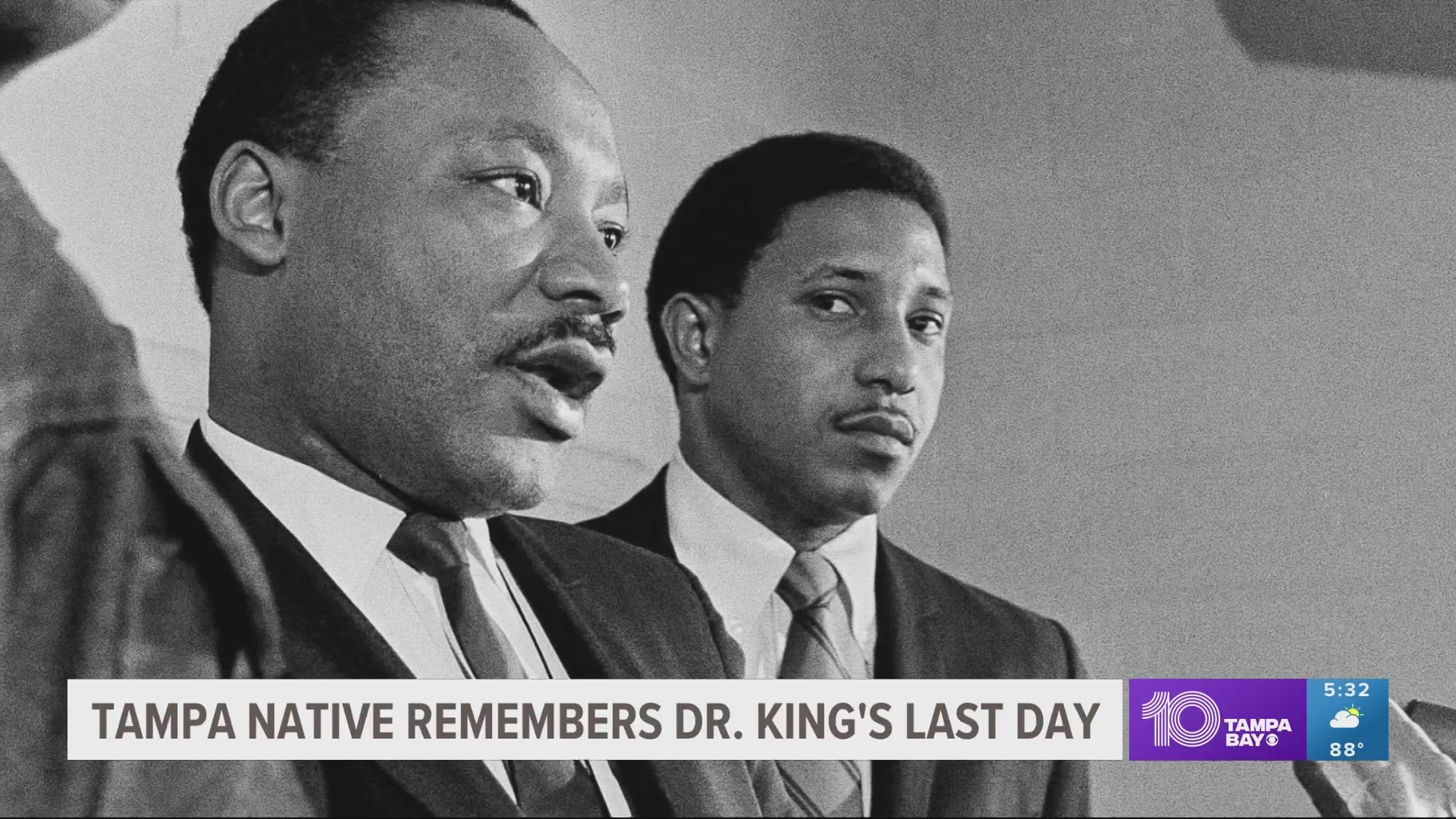

TAMPA, Fla. — On April 4, 1968, Bernard Lafayette, Jr. of Ybor City was with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, putting the finishing touches on a press statement for the launch of King’s Poor People’s Campaign in Washington. Little did Lafayette know it would be King’s last day alive.

10 Investigates’ Emerald Morrow sits down with Lafayette, who got his start in the civil rights movement during sit-ins with his college roommate, John Lewis. He later became a Freedom Rider and attracted the attention of Dr. King, who appointed him to leadership roles with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Poor People’s Campaign.

Here, Lafayette talks about the hours leading up to King’s death, how he got the news and how he’s kept King’s dream alive 55 years later.

NOTE: This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Emerald Morrow: Tell me about April 4, 1968.

Bernard Lafayette: We were in Memphis, Tennessee, because Martin Luther King had been invited to support the sanitation workers there…because they were on strike, trying to form a union.

They were going to do a march…but once Martin Luther King had the march, it turned out to be violent. Some of the local gang people got downtown and became very belligerent and broke down windows.

So, Martin Luther King did not want that to be the last in terms of his legacy, so he wanted to do the march over again.

In the meantime, Martin Luther King was scheduled to go to Washington D.C. to announce the location of the Poor People's Campaign headquarters in Washington D.C. So, he wanted me to go ahead and have that press conference, because he didn't want to stop having press conferences simply because of what happened in Memphis.

And since I was a national coordinator of the Poor People's Campaign, that's what they wanted to announce. I said, 'OK.' So, I spent most of the day in Memphis with Martin Luther King writing out the press statement.

So, that morning of the fourth when I got ready to go to Washington D.C., I went by his room. His room was 306, mine was 206 in the Lorraine Motel.

When I went there to get the final touches on the press statement, when I finished, he said, 'Well you go on to Washington D.C. and get things started, and I'll be along.’

Then as I put my hand on the doorknob to leave his room, he said, 'Now there's another thing, Bernard Lafayette. I want you to know that our next move is going to be to institutionalize and internationalize nonviolence.' I said, 'OK.' So, I went out the door.

When I got to the airport in Washington D.C., my ride was not there. Walter Fauntroy was supposed to pick me up and he was not there.

So, I called back to the office to find out and that's when they told me he had been shot, Martin Luther King had been shot in Memphis. So that was the first thing that I heard about his death.

Emerald Morrow: What did you feel in that moment?

Well, I didn't think he was gonna die simply because he was shot. Because he'd been stabbed in Central Park earlier by some lady with a letter opener.

So, I got on the telephone in the telephone booth...in the airport in Washington D.C., and I was able to make two telephones at one time. I dialed the AP, Associated Press, and UPI, United Press International.

I had one phone in one ear and one in the other, and I wanted to get a report on what happened in Memphis with Martin Luther King. And they started reading me the ticker tapes because they used to have ticker tapes, that's how they communicated in those days.

The reporter for UPI all of a suddenly stopped reading the ticker tape and I could hear him sniffling, and he was completely silent otherwise.

So, that's when I came to the conclusion that Martin Luther King had died. He never told me that Martin Luther King had died, but his silent reaction, you know, made me know that's what happened. Finality.

Emerald Morrow: How did that moment change you?

Well, I called the office there to find out what I should do, whether I should go back to Memphis or go to Atlanta or where should I go.

So, I went on to the office there in Washington, D.C., and I felt committed to finish what Martin Luther King wanted to do. Those were the last words. You know, he told me, "'Go on to Washington, D.C., and get things started.'"

I was so preoccupied with that assignment that I didn't have time to grieve. I have not grieved yet. I have been so committed and so devoted to accomplishing those goals that he wanted. Had he been here and lived, what would he do?

Since he was no longer with us, could his work be continued? And he made it very clear what he wanted to see happen. So, I had to prepare myself to do what I could do with my life in order to continue what Martin Luther King would have done had he lived.

I knew that I could not fill Martin Luther King's shoes. I don't think anyone could have done that. But at least he said directly to me what he wanted to do with his next movement, and he told me that. So, therefore, he expected me to complete the job. And that's what my life had been devoted to.

Since King’s death, Lafayette has worked to further King’s mission of nonviolence as a scholar-in-residence at The King Center and Auburn University. He’s also served as director of the Center for Nonviolence and Peace Studies at the University of Rhode Island.

Emerald Morrow is an investigative reporter with 10 Tampa Bay. Like her on Facebook and follow her on Twitter. You can also email her at emorrow@10tampabay.com.