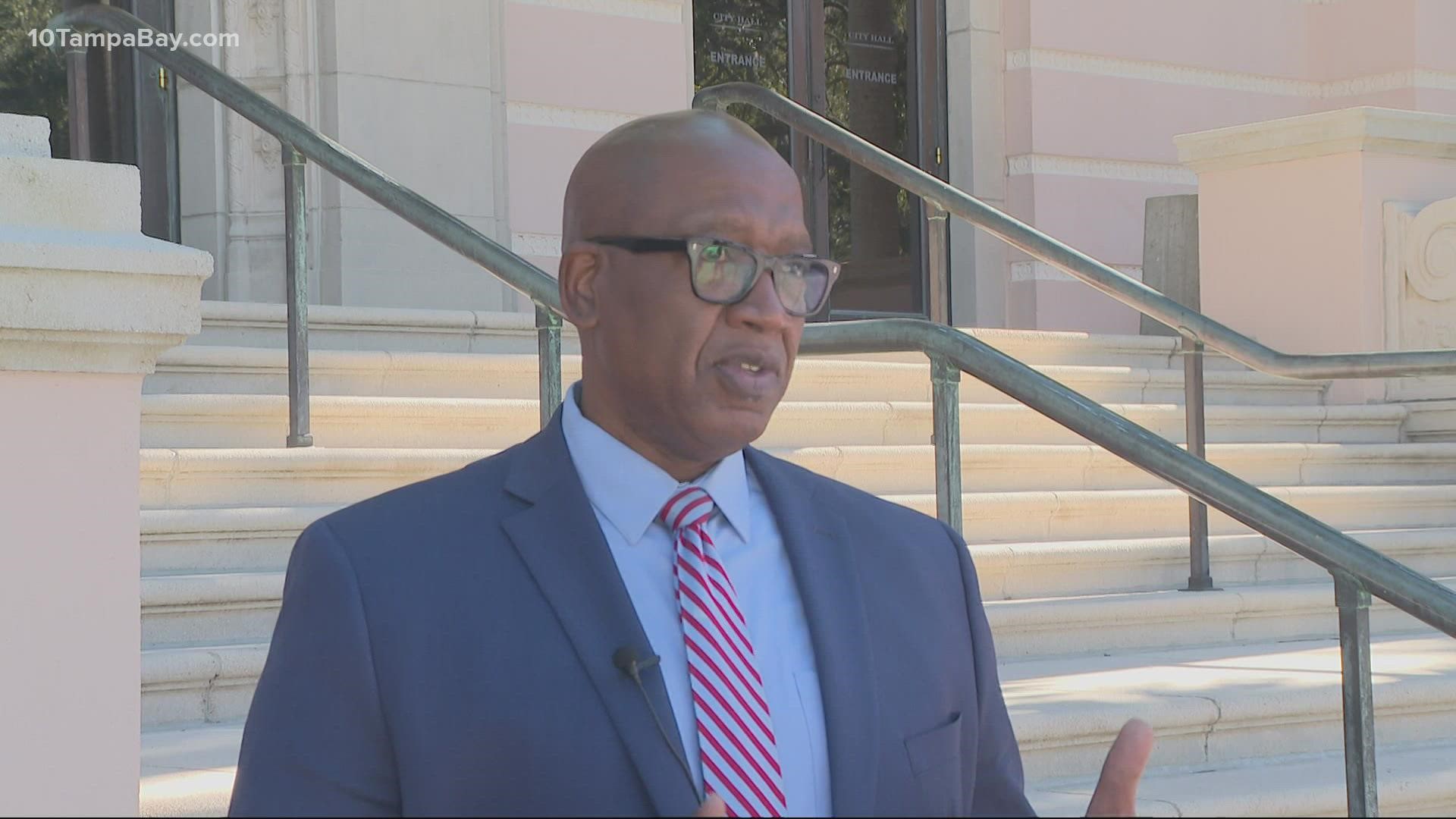

SAINT PETERSBURG, Fla. — Born into a family of firsts, St. Pete Mayor Ken Welch has become a trailblazer in his own right as the first African American to lead the city.

To close out Black History Month, Mayor Welch spoke with 10 Tampa Bay’s Emerald Morrow about what the historic role means to him and where he hopes his vision will lead the city of St. Pete.

NOTE: This conversation has been edited for length and clarity

Reporter: What does it mean to you to be St. Pete’s first African American mayor?

Welch: And you know, it's really exciting that, that is what carried this election that, you know, folks looked at the totality of my message, my experience and what I brought to the table and voted based on that, and I think that is the essence of what Dr. Martin Luther King dreamed about.

Reporter: You come from a family with strong political leadership. How has that legacy influenced and prepared you?

Welch: My father served in this building as a city councilman, the first African American city councilman in 1981. And so, I understand what service is about.

He talked to everyone. He went to where the people were. He didn't have, you know, a different approach based on your income or your status. He treated everyone the same. And that's really the essence of what inclusive progress means. That means everyone has a seat at the table. You know, whether you're a downtown developer, whether you're a person in a neighborhood who's being impacted by traffic or violence or the affordability of housing, everyone has a seat at the table. And I think that's probably the most important thing I learned from my father.

Reporter: How do you plan to address housing affordability in a city that is pricing out many of its residents? How do you balance that with maintaining relationships with developers?

Welch: So, when we talk about affordable housing, we had an issue [in January] where there was a proposal for townhomes that would be affordable to folks making $60,000. Well, the median income is about $50,000. So, half the people here make less than that. And so, my conversation with staff is we need to make that lower because the people that live in that area don't make $60,000.They make $40,000.

So, if we're not intentional about making sure there's affordable housing for the folks who are here, then we will contribute to gentrification. It's just that kind of what I call intentional equity and being focused on affordable housing as a priority that we bring to the table.

We've got partnerships, we've got resources. The "Penny For Pinellas" has a large amount for affordable housing, the infrastructure bill and the "Build Back Better" plan from the Biden administration have dollars for affordable housing. We want to tap into all those sources. Bring the dollars down, work with developers and get the affordable housing on the ground.

Reporter: Talk more about the community benefits agreement, which considers the impact developers and their developments have on the surrounding communities.

Welch: It means when there is a development that meets a threshold, it has a certain amount of city investment in it, then it should have some community benefits and those benefits can be determined by a community group, an advisory group.

It could be affordable housing, it could be payment into a fund that supports other community development projects, but it's basically saying when you receive city contribution to your project, you pay back the community through this CBA.

City Council has already approved it. We're waiting now for the first developments to utilize that CBA, but it's an important part of making sure the progress that we see in the city is inclusive for everyone throughout the city.

Reporter: African American neighbors, businesses and other institutions from the Gas Plant neighborhood that were displaced when the city wanted to build Tropicana Field have been looking for justice for decades. How do you plan to address their concerns as the city again looks to redevelop that area?

Welch: I've met with most of the massive development groups who submitted proposals. And so, they all understand that essential equity is a priority for me that, that development needs to speak to the promises that were made more than 30 years ago—that uplifts the community through jobs, through economic development.

The Kriseman administration did a great job in laying out the RFP and it has these principles in it, which include minority contracting, minority hiring, affordable housing, but also that community benefits piece because, you know, I grew up in the Gas Plant and it was a community. There was a lot of mentoring there. There was a lot of care for young people, especially when that community was uprooted and displaced. You lost that sense of community.

And so, what I want to see this development contribute is fund those programs throughout the city, that kind of rebuild that sense of community: Mentoring for our young people, education, all those things that were displaced when the Gas Plant was uprooted.

Reporter: Parts of St. Petersburg have really struggled with violence, especially through the pandemic. What is your plan to address this problem in these communities?

Welch: What we consistently heard is, ‘we don't see a way to connect with this opportunity that you keep telling us about.’ And so, what I want to do is what we call empowerment and innovation centers.

I want to upgrade our community centers so that they have digital access, safe places for mentoring, out-of-school time and make them modern places where kids want to come to. So that'll be an investment from the city as well.

You’ve got to reach young people where they are. And so, there are a lot of young people who are struggling day-to-day. The other thing we heard was young people saying they're dealing with mental trauma, because of the violence, so you've got to reach kids where they are. It can't be asking them to come to city council or come downtown.

We've got to go where the kids are, provide the resources, including the wraparound services. And it might be risky in some cases, they might have to be messengers—folks who have been in the system who can tell kids what the experience is like. But we need to take those risks and innovate and that's what we're looking at.