RUSKIN, Fla. — Allow us to set the scene: It's World War II. You're a soldier overseas. Your friends and family promised to write. But you haven't gotten a single letter in months. Morale was low, and in the darkness of war, you wonder if you're lucky enough to make it home, there will be anyone there to greet you.

In the mid-1940s, there was a shortage of soldiers able to manage the postal service for the U.S. Army. And there was also an underutilized demographic in the U.S. – Black women.

After calls for Black women to be given opportunities to serve in meaningful roles in the war overseas, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt gave her support. Women signed up and were sent down to Fort Benning, Georgia for training.

More than 6,000 Black women served in the Army Air Corp and Service Corp during WWII.

Gladys Blount was one of 855 women chosen to be about of #6888 WWII Central Postal Directory Battalion.

She was working in a beauty parlor and shared with a smile, that it was the lack of eligible bachelors that encouraged her to enlist.

"I went in because there weren't any fellas around, just boys and old men," Blount said. "So I told my sister, there's nobody around. She said, why don't you just join the army? I went down the next day and joined."

She made her way to Rouen, France to get to work. And there were fellas overseas. When asked how she managed to get through long shifts of sifting mail, Blount didn't hesitate to answer.

"In the evenings the fellas would come around and we'd have champagne," Blount said.

Batallion #6888, nicknamed six-triple-eight, sifted through a six-month backlog of mail overseas in just three months. The women sorted through old mail and packages, estimated to be roughly 17 million parcels.

"We put the new addresses on the envelopes and forwarded them on," Blount described.

Blount and the women she served alongside reconnected soldiers to their loved ones in a time they needed it most.

"They were brave," Blount said of the women she served with. As for herself, "very proud," she said.

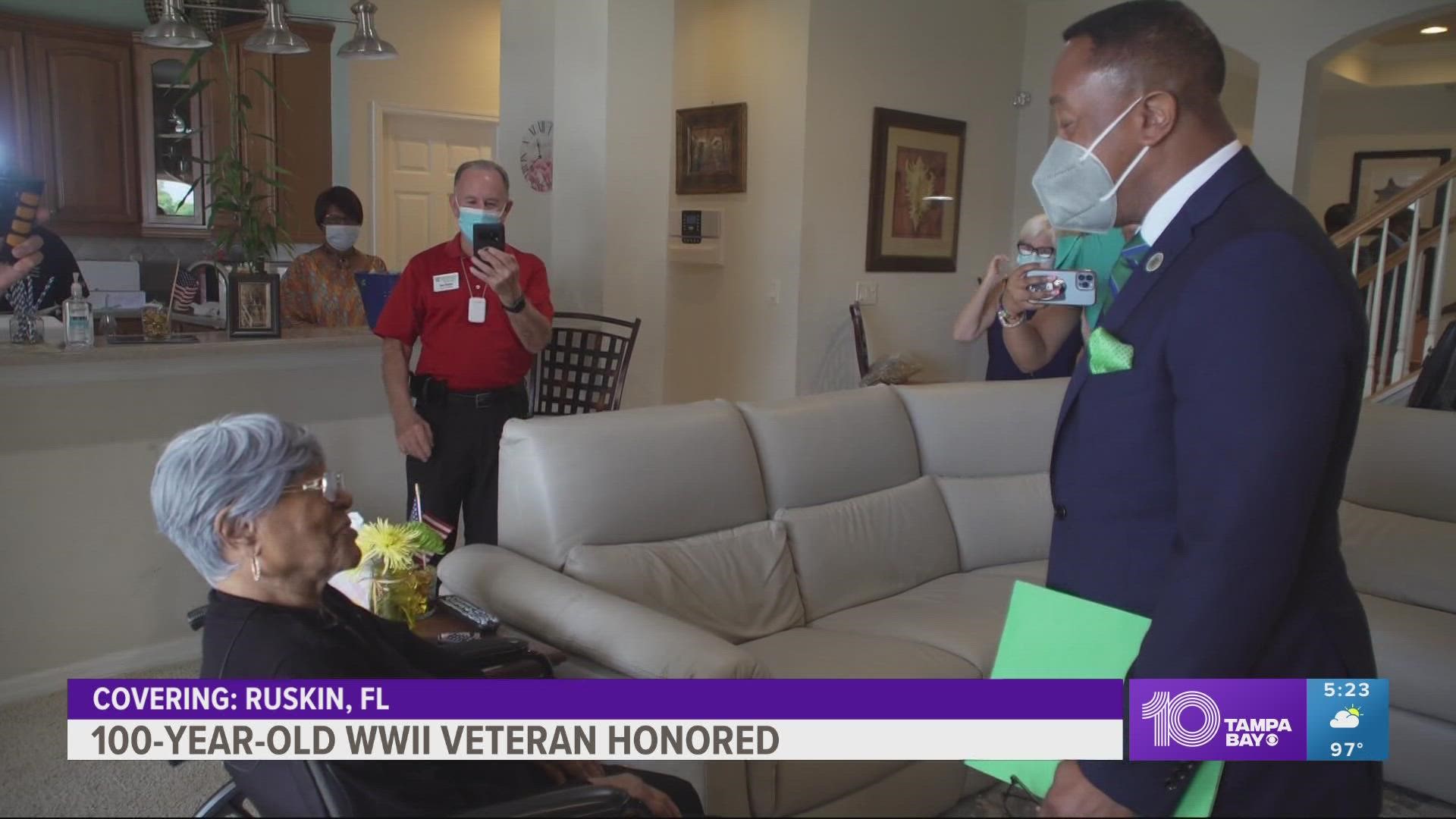

On Friday, her hometown mayor of East Orange, N.J., flew down to where she currently lives in Ruskin to honor her service. East Orange Mayor Ted Green presented Blount with a proclamation from the city, a key to the city, and a city medal of honor for her global contributions.

"I am surprised! I thought I was a forgotten subject," Blount said.

Now the world and her own kids know more about what she did.

"Not only am I proud of her," Blount's daughter Eva Davis said, "I'm learning more and more about her as she expresses herself."

Blount is reportedly one of just six surviving members of her 855 all-Black, all-women battalion.

#6888 recently received the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation's highest and most prestigious military decoration.