'Heads, you're probably OK. Tails, you get sick': University Area battles unsafe water from wells, septic tanks

Researchers cite "municipal underbounding," a process by which lower-income, minority neighborhoods are often excluded from city boundaries.

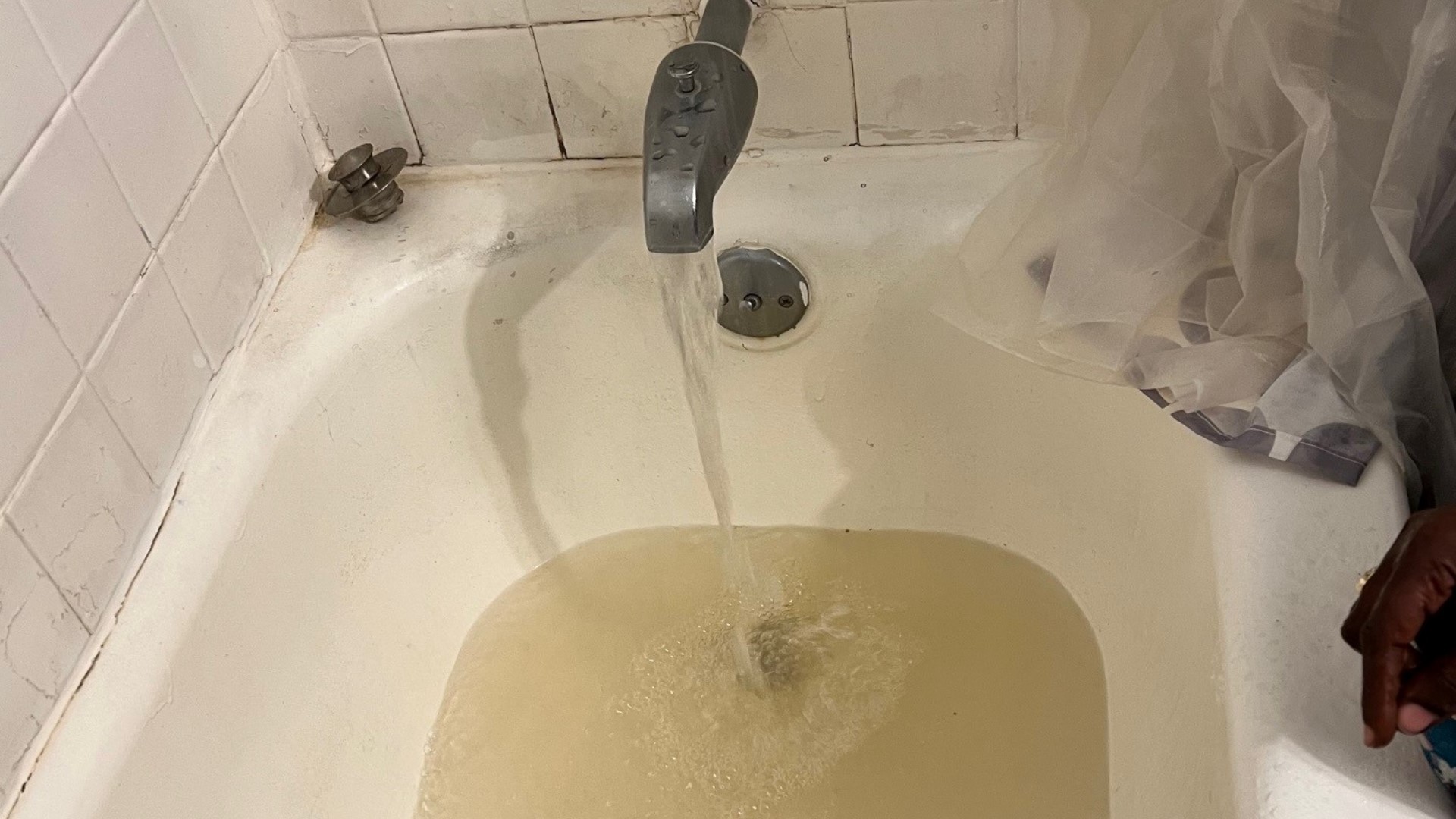

Water that comes out brown, irritates the skin and has a chemical taste and smell — these are just a few of the water woes people in the University Area of Hillsborough County say they have lived with for years.

Researchers estimate as many as 1,300 homes are still connected to well water and septic systems. Over time, some of those systems have failed, leaving residents with water that is sometimes unsafe to use or drink.

"Drinking tap water in the University Area community is like tossing a coin. Heads, you're probably OK. Tails, you get sick,” said Dr. Christian Wells, a professor of anthropology and director of the Center for Brownfields Research and Development at the University of South Florida.

Wells began investigating water quality complaints in the University Area in 2017 after learning about complaints among neighbors living at Holly Court Apartments on N. 20th St. At the time, the complex was being serviced by well water.

A 2021 memo he sent to Mayor Jane Castor says water testing done by the Florida Department of Health "revealed elevated levels of iron that exceeded the maximum contaminant level (MCL) by as much as 7 times that established by the Safe Drinking Water Act."

Wells also said other forms of contamination could be present.

"There's everything from situations where a private drinking water well will be located within a drain field of a septic system and that the pipes from the drinking water well are old and deteriorating,” he said. “And so, you get fecal contamination into that. Coliform, E. coli and that sort of thing."

Wells said people in and around this area who are on city water and sewer service can also experience problems.

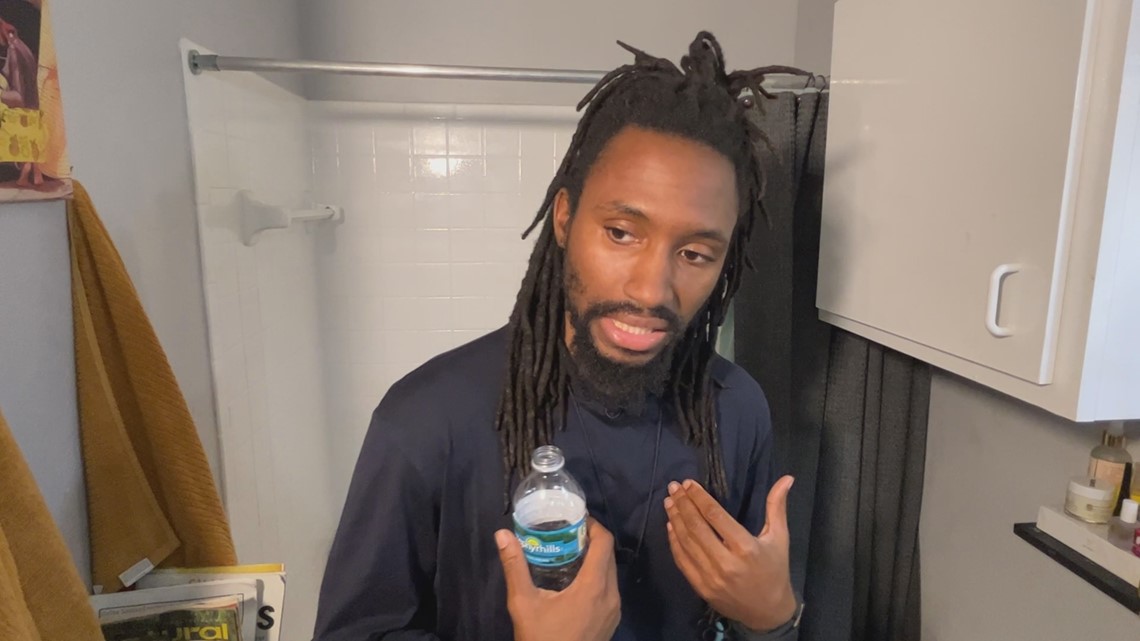

Ernett Harris says he can attest to that. Harris, who lives in an apartment close to the borders of the University Area, says he does not feel the water is safe to drink. He says there is often a smell of chlorine or sulfur when he turns on his faucet, and it can sometimes cause irritation.

"Sniffling real bad. Runny noses. My eyes won't clear up," he said.

Wells said that can be common.

"We've talked to people… on city water, but they have rashes, itching, skin problems, gastrointestinal problems, even though they're on city water,” he said. “And that's really due to the aging housing stock and problems with domestic plumbing."

This raises questions and concerns about how an area so close to the city boundaries of Tampa could have these problems.

Municipal underbounding Some, mostly minority, communities are being intentionally excluded from city boundaries.

"Even though the water main might be available, people aren't tapped into it. This is a process that's been fairly common over the past century in the southeastern United States, especially in Florida, that we call ‘underbounding,’" Wells said. “And this is the exclusion of communities from city boundaries and disinvestment in those communities, largely because of a legacy of residential racial segregation."

The University Area borders the city limits of Tampa and is commonly defined as the area between Interstate 275 and Bruce B. Downs Boulevard from Fowler to Bearss avenues. The area is mostly minority and low-income.

"It's not just, you know, around Tampa. In any of the major metropolitan areas in Florida, you'll find communities — Black, Hispanic, indigenous, people of color, communities that are not within city boundaries, even though they're there right on the border. And so they don't have the benefit of municipal citizenship,” Wells said.

The Progress Village community in Hillsborough County and Tallevast in Manatee County are other local examples. Flint, Michigan, and Jackson, Mississippi, are examples known across the nation.

"That is always the case that those suffering the worst are low-income minority communities,” Wells explained. “And this is a legacy, a long-term legacy of residential racial segregation and disinvestment over long periods of time."

In the University Area, researchers say most people on well water and septic systems are renters, and landlords are sometimes hesitant to convert because of cost.

"That...is just a whole 'nother layer of complexity, is trying to get these landlords to understand, you know, their properties and the conditions in their properties and how this is affecting our residents,” said Dr. Sarah Combs, CEO of the University Area CDC.

Florida's septic problem Septic tanks cause 42% of the nitrate problem in Florida's freshwater springs.

Beyond the University Area, there are tens of thousands of parcels in surrounding counties still on septic tanks. 10 Investigates found that of all the counties in our viewing area, Hernando has the highest percentage of septic parcels, at nearly 45 percent. Citrus came in second at 35 percent.

This matters whether you like to be out on the water or want the best quality from the faucet. The Southwest Florida Water Management District says septic tanks cause 42 percent of the nitrate pollution in the state's freshwater springs.

"Nitrate is chronically toxic to humans,” Dr. Bob Knight of the Florida Springs Institute said. “It's acutely toxic when it's in high enough concentrations, so this is the same water that we drink, and we should be worried about that."

However, the septic tank solution is not cheap. That’s why Hillsborough County is paying to get homes connected to sewer and water services.

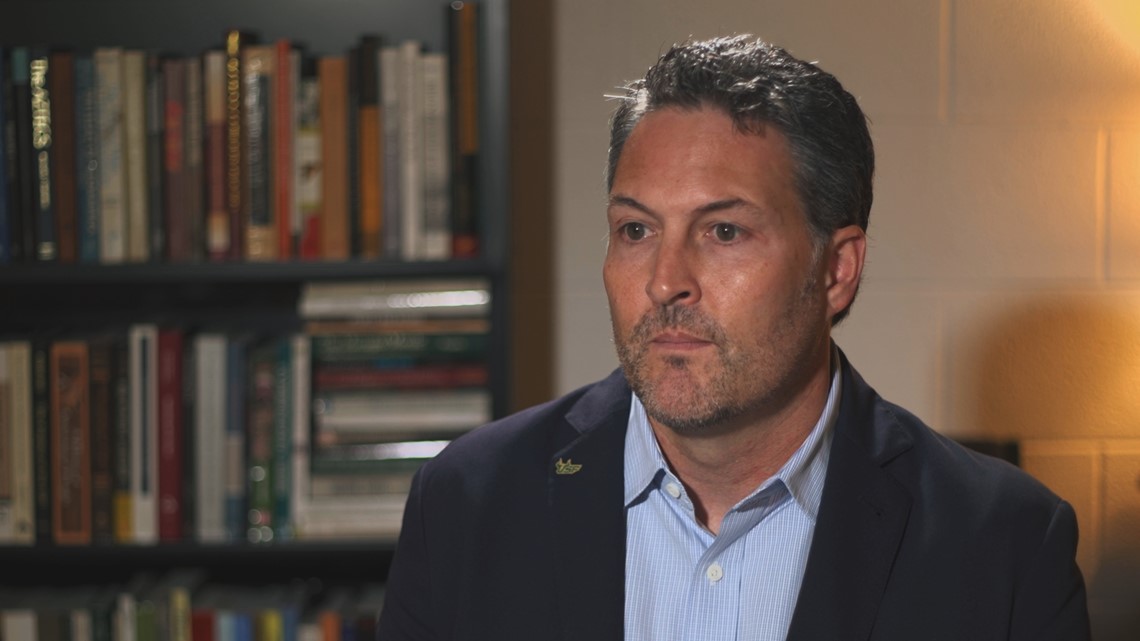

“We have some grant funds that were made available by our board through the ARP funding and it's about $3 million,” said George Cassady, Assistant County Administrator for Hillsborough County. “And that money is being used to basically make the whole conversion at no cost to the resident, to the property owner."

There are some exceptions, including properties that require constructing a pump station or line extension that requires crossing a major road.

Still, Wells says any assistance matters.

"The more we can bring light to the water and sewer issues that are in that University Area community, I think the more people will be paying attention, especially the people in inner city and regional government that can really move the needle on this and make a positive change,” he said.

Emerald Morrow is an investigative reporter with 10 Tampa Bay. Like her on Facebook and follow her on Twitter. You can also email her at emorrow@10tampabay.com.