No plans for search despite evidence suggesting graves under shuttered Catholic school property in Tampa

The Diocese of St. Petersburg says all graves were moved. 10 Investigates found historical evidence that conflicts with that statement.

The last seven years of Alexia Svejda’s search for her great-grandfather’s grave left her with more questions than answers.

“I started searching summer of 2014, and nobody knew about the cemetery," she said. "I tried every avenue I possibly could."

Her great-grandfather, Bernardo Alvarez, came to Tampa from Spain in the late 1800s and built a career in Ybor City’s thriving cigar industry. A gunshot wound cut his life short in 1907.

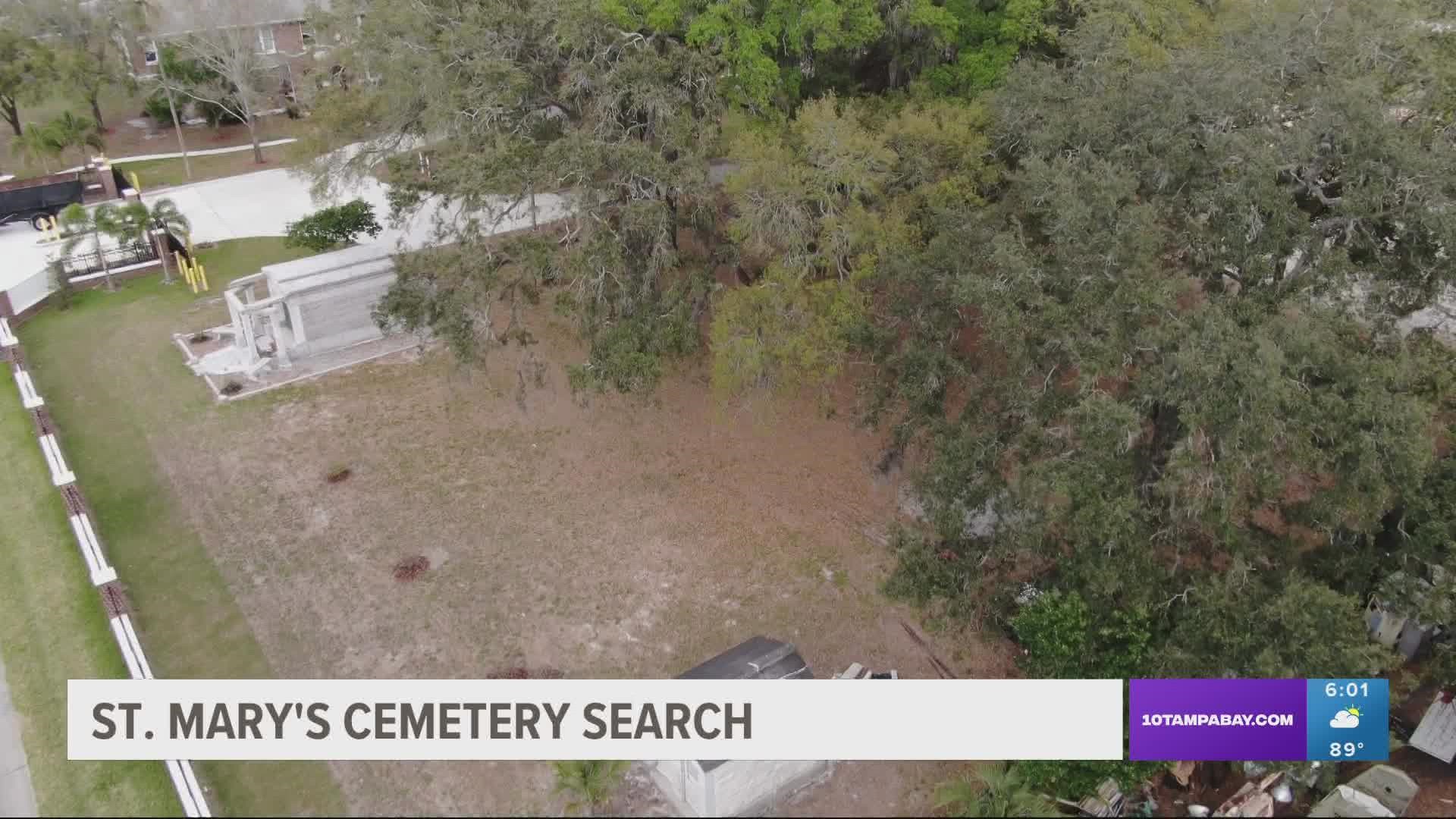

His family laid him to rest in St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery off N. Florida Avenue in Tampa. Today, the Diocese of St. Petersburg owns the property, and the shuttered Sacred Heart Academy occupies the space.

A spokesperson for the diocese insists graves were moved before it acquired the property from the Diocese of St. Augustine in 1968.

Records do show some graves were relocated to a section of Myrtle Hill Cemetery in Tampa. But with death records suggesting anywhere from 400 to 800 or more graves from St. Mary's at some point, archaeologists and loved ones of those buried there say it’s a strong possibility bodies are still buried on the site.

HALLOWED GROUND The nine to 10 acre plot of land had the potential for thousands of graves.

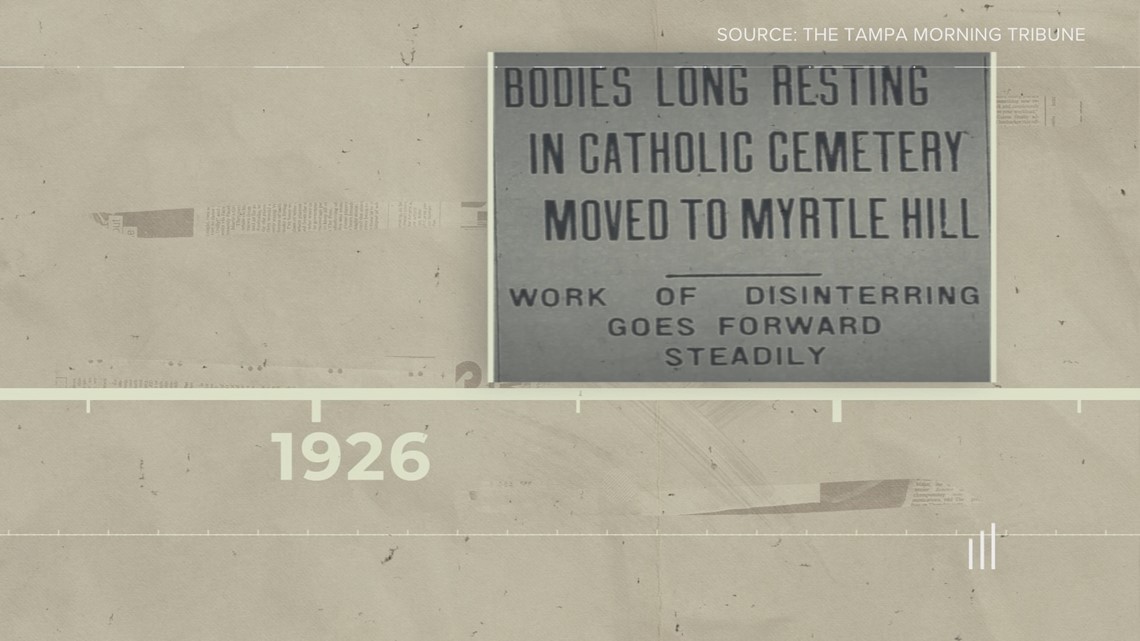

According to newspaper records, religious leaders voted in the mid-1920s to move about 400 graves from St. Mary’s to Myrtle Hill to possibly make room for a school. A 1926 article from the Tampa Morning Tribune reports Catholic leaders believed the area was “adaptable” for this kind of project. Others disagreed, saying the land was hallowed ground.

The project moved forward, with records suggesting about 100 graves moved by 1926.

However, neither Myrtle Hill nor the Diocese of St. Petersburg were able to share records showing the move was ever completed. Service Corporation International, the company that owns Dignity Memorial and its subsidiary, Myrtle Hill, said it would research the issue but could not find any records. The only documentation available was on the Myrtle Hill website confirming receipts of 100 graves from St. Mary’s. Nothing more.

10 Investigates has been requesting an interview with the Diocese of St. Petersburg on this topic for months. The diocese declined our request for an interview, but said in a statement:

"We respectfully decline your request for an interview. However, I can tell you what we have stated in the past. The land that became Sacred Heart Academy was, in part, a graveyard (St. Mary’s Cemetery) with two mausoleums. All the remains were moved from there to Myrtle Hill Cemetery in Tampa. The two mausoleums are still there. Also, we cannot provide reinterment records to media outlets because they are considered private. The Diocese of St. Petersburg acquired the land in 1968, after the remains had been removed."

The statement doesn't persuade Svejda, who reached out to 10 Investigates after seeing an initial report on St. Mary’s in 2021. She says recent discoveries of other destroyed and erased cemeteries across the Tampa Bay area like Zion, Ridgewood and North Greenwood further solidify her stance.

“Oh, I'm convinced. Especially with what I'm hearing now out of Tampa," Svejda said. "I was quite convinced then and I'm even more convinced now that his remains were never moved."

Maps and records from the early 1900s show the land for St. Mary’s was somewhere between nine and 10 acres. It’s not clear if the entire property was used for burials, but the size suggests far more graves than what has been recorded.

“Generally speaking, an acre of property could potentially have 800 to a thousand burials, assuming they’re not stacked,” said Dr. Erin Kimmerle, a forensic anthropologist at the University of South Florida.

LIKELIHOOD OF GRAVES Archaeologists say cemetery moves are difficult, and it’s reasonable to believe graves could still be on the old school property.

Jeff Moates has played a major role in uncovering a dark chapter in the Tampa Bay area’s history. The archaeologist was recently head of the Florida Public Archaeology Network at the University of South Florida, where he used research and ground-penetrating radar to help uncover hundreds of graves from the destroyed Zion Cemetery in Tampa. He also worked on similar projects at destroyed and erased African American cemeteries in Clearwater.

There, 10 Investigates revealed how the Pinellas County School District had knowledge that a cemetery existed on one of its school properties but had been told all the graves were moved.

RELATED: Maps confirm cemetery existed on Clearwater school property, but were graves properly removed?

Moates, who now works for PaleoWest in St. Petersburg, says that is a common theme.

"It's difficult to trust those statements. Relocating cemeteries, relocating burials is a difficult process today, it was difficult a hundred years ago," he said, adding that property owners should practice an abundance of caution when they know a cemetery existed on their land.

"The likelihood there are still some remains there are high and especially over the lessons that we've learned over the last several years," he said. "Relocating human burials is a difficult process and it's not always the most thorough—and that understanding the law that human remains are protected whether they are on public or private property."

PRESERVING THE PAST Archaeologists say two current mausoleums, evidence of prior graves and the possibility of more remains are enough to register the site with the state’s division of historical resources.

It’s hard not to miss the two mausoleums housed behind an iron gate not far from the old Sacred Heart Academy that first opened in the 1930s.

The question is: Could that classify this area as an existing cemetery?

“I could say, probably, yes,” Moates said. "Whether or not there are remains still in those mausoleums is the question that I think we're trying to answer. The mausoleums are historic structures, and they were a part of a cemetery. So, I think that evidence alone and that there was a cemetery there that you can say that it's plausible that this is still a cemetery and should be treated as such."

Getting the site marked happens through the state.

"It's a simple process through the Division of Historical Resources," Moates said. "It's called a Florida master site file and that can be filled out and it's basically documentation that says there was a cemetery here and there's information that may lead us to believe there's still some remains located in this property."

After learning about 10 Investigates’ research into St. Mary’s, an archaeologist at the University of South Florida started this process, so it's officially on the record and has some protections in place.

"It can be part of a review process, so if there was ever any sort of construction or development planned for that particular parcel, the parcel would get flagged potentially as a cemetery and there would need to be some due diligence that occurs at that point before any of the ground-disturbing activities occurred," Moates explained.

However, those protections are limited. Sometimes there's a disconnect between the state and local levels because there's nothing requiring local governments to review the Florida Master Site File.

State Rep. Fentrice Driskell (D-63rd District) tried to address this with legislation that would have created an Office of Historic Cemeteries. But it never came to a full House vote.

"We always thought, 'Well okay, this just means this is another battle that we have to take up next legislative session,'” Driskell said.

Still, she calls on The Diocese of St. Petersburg to take action, even if it's not required.

“I think you really have to consider what is the right thing to do,” she said. “And when you have this descendant community that's looking for their loved ones, the right thing to do would be to allow for something non-invasive like ground-penetrating radar to try to find out if those graves are buried there."

Something Svejda would love to see.

"Well, the sooner the better. Because I would really like to visit with my dad and with my cousins. They're not getting younger..." she said. "They want closure. They want to know where are they, what happened? Especially with my great-grandfather. There's nowhere to go, there's nowhere to visit. There's nowhere to connect those memories. And I want to give them that connection."

Emerald Morrow is an investigative reporter with 10 Tampa Bay. Like her on Facebook and follow her on Twitter. You can also email her at emorrow@10tampabay.com.