Florida’s building codes: The next hurricane could blow them away

The battle between man and nature plays out each hurricane season: Can homes be better built to withstand the power of a mighty storm?

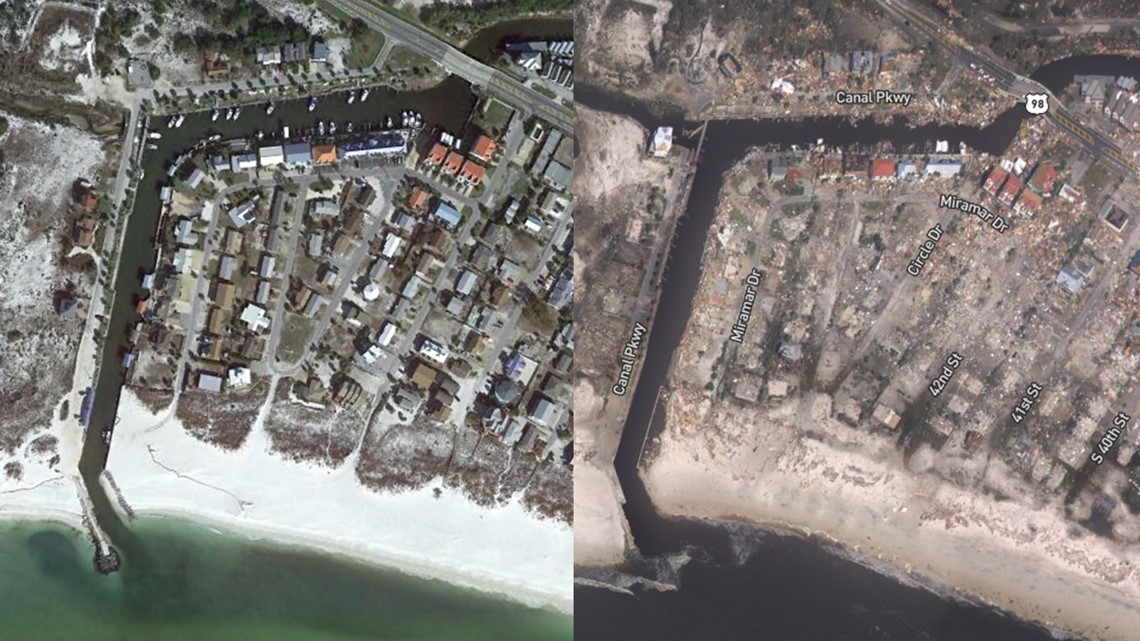

Total devastation.

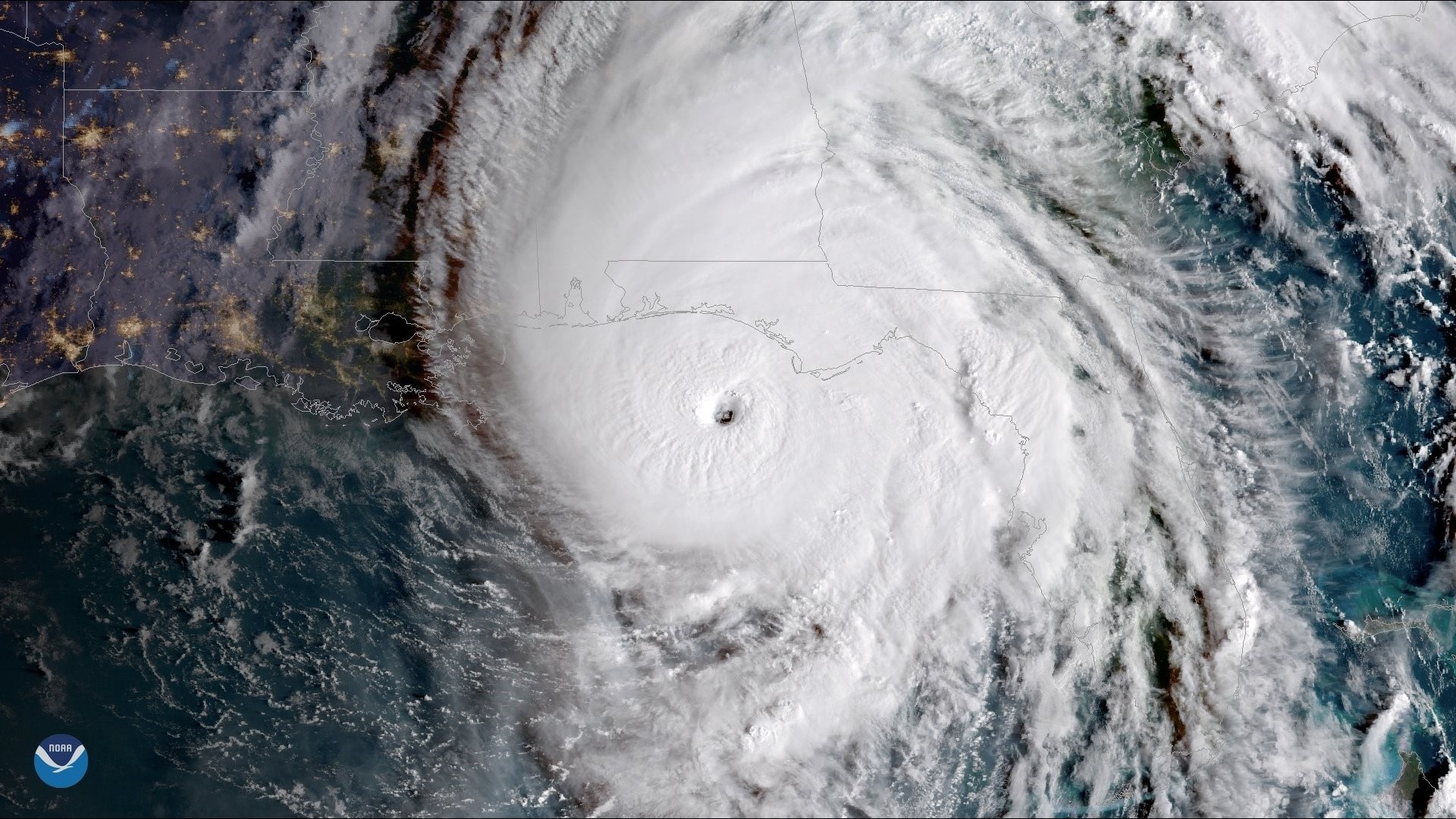

That's what we saw along parts of the Florida Panhandle last October when Hurricane Michael roared ashore at Mexico Beach.

It's immediately evident: Our buildings are not capable to withstand this type of power.

Were they supposed to? If not, why not?

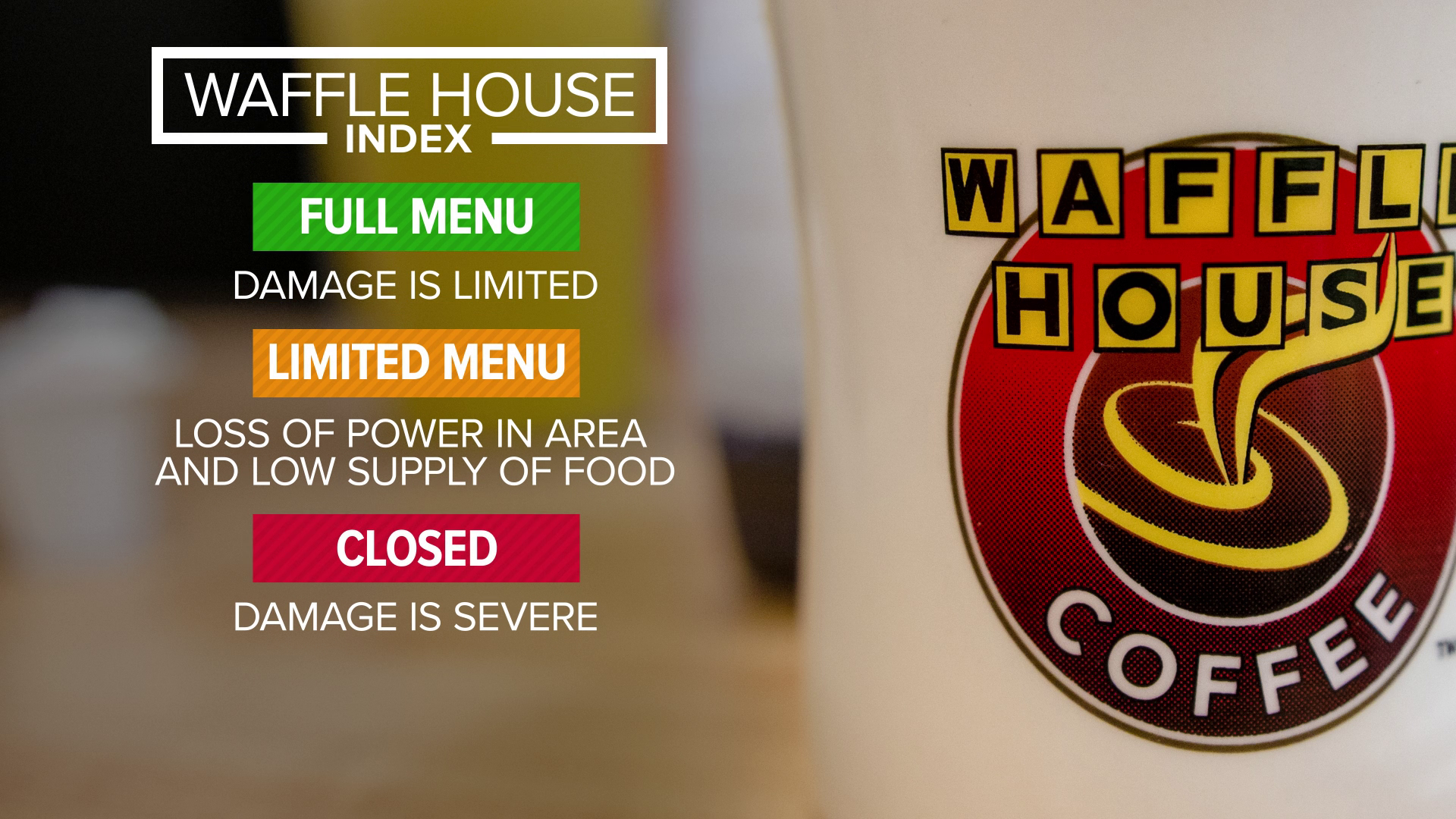

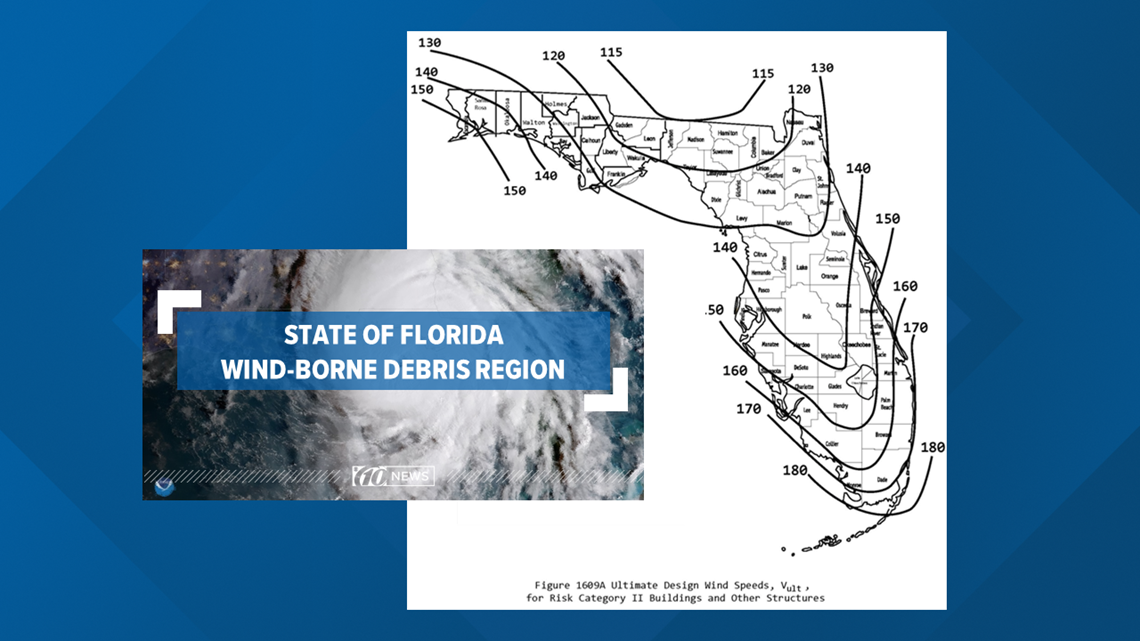

Building to code: Man vs. wind The Florida Building Code aims to standardize how new construction can be built to withstand hurricane-force winds.

Hurricane Michael leveled the beachfront community of Mexico Beach, leaving it just about unrecognizable from devastating wind and storm surge.

Nearly six months later, the National Hurricane Center upgraded the system to a Category 5 storm – the highest level on the Saffir-Simpson Scale – with maximum sustained winds of 160 mph.

The tiny city still is struggling to recover.

It goes to show the power of even the most intense hurricanes, especially considering Florida is known for having the most stringent building codes in the country.

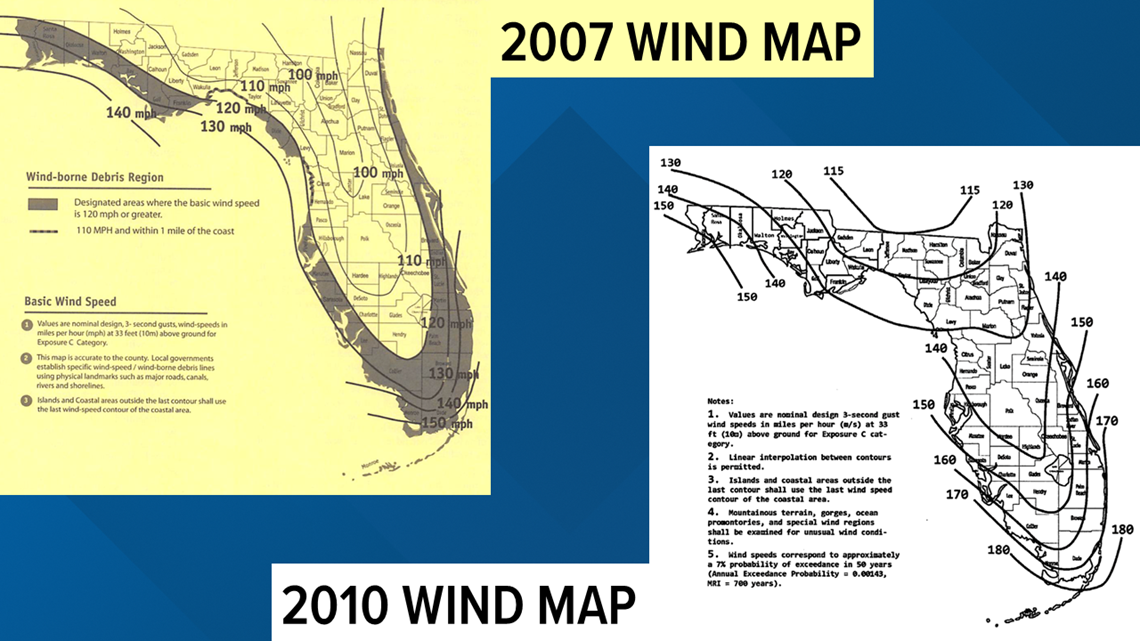

Since Hurricane Andrew in 1992, the last Category 5 storm to slam the state, Florida has been divided into several wind zones designated in the Florida Building Code. Based on what region you’re in, your home has to be built to withstand winds in that area’s wind zone.

The strictest wind zones are down in South Florida. New construction in the Florida Keys needs to be built to withstand up to 180 mph, for example. Up in the Panhandle, like Bay County where Michael hit last year, wind speeds are significantly lower to 130-140 mph.

Now, people are asking if a change is needed.

Marvin Dryden, Tampa's construction services center manager, thinks codes are where they need to be currently.

"Yeah, I think they are, if they’re properly applied to construction today," Dryden said.

He does acknowledge, however, there are thousands of homes in the Tampa Bay area that were built before Hurricane Andrew and are likely not up to code.

The counties surrounding Tampa Bay all fall in the middle range of Florida’s wind codes – from 160 mph in parts of Sarasota County – to 140 mph in parts of Citrus, Hernando and Pasco counties. Dryden estimates that only about a quarter of homes in the city of Tampa are up to the current code because many are older structures.

It could be even fewer homes in some of the surrounding areas.

What if a storm like Michael were to hit here?

"We’re looking at a small area when we look at the devastation they had in [Mexico Beach]," Dryden said. "Because we have so many more homes and it’s such a wide area, we wouldn’t see that area of widespread devastation.

"It would be a focused area of devastation."

Dryden believes some parts of the Bay area with older homes could have a lot of structural damage if a storm like Michael hit here, but he doesn’t think the Bay area would see whole communities wiped out as we saw in Mexico Beach.

"We look at Mexico Beach and the devastation there," Dryden said. "What we see there is a small area. This is a much larger area, with a bunch of different types of construction, different ages of homes."

Other experts, like former Federal Emergency Management Agency director Craig Fugate, disagree with the local assessment.

"It would be worse in Tampa Bay," he said.

Fugate served as head of the FEMA under the Barack Obama Administration. Now in the private sector, he’s still an expert when it comes to hurricane damage.

"I’m not sure our building codes are as good as they need to be," Fugate said. "What happened in the Panhandle could happen anywhere along Florida’s coast."

According to hurricane tracks collected by NOAA through the years, it’s clear the entire state of Florida is a potential target – and there might be a problem with setting standards solely based on what’s happened in the past.

"Looking at past data to determine our vulnerabilities and risk isn’t working, particularly for hurricanes. How many times in the last 10 years have we had record-setting weather events?" Fugate said. "You cannot just go by the history of the hurricanes, you have to ask the question: Is there any reason why it can’t happen?

"Just because it hasn’t, or hasn’t happened in our recorded history, doesn’t mean it hasn’t happened or cannot happen."

So what is stopping state leaders from bolstering the state’s wind codes? Experts say it all comes down to politics.

"Politics are absolutely the factor we have to address," Fugate said. "Building codes are formed by commissions of various vested interests. It is, at the point a code is issued, already a compromised document.

"It is not always what the best science is, it is what everybody could agree to."

Fugate says, traditionally, it has been those special interests who have lobbied to weaken the state’s building code arguing that strengthening the code would only amount to more red tape.

"Red tape is what, in many cases, provides for the basic safety of our homes," Fugate said. "This is something that the Florida legislature has to address.

"It’s something that the cabinet has to address and it’s something that Governor DeSantis at least is recognizing that the long-term trends are not in Florida’s favor."

Gone in an instant The "Wall of Wind" at Florida International University puts building materials to the test.

Denise Bradford’s home took a beating in Hurricane Irma – built in Tampa in the 1960s, long before any wind zones were implemented in 1995.

Irma had no trouble pulling her house apart.

"People say, ‘I don’t think that would ever happen to me,’ but you don’t know what will happen to you until it actually happens," Bradford said.

And it’s going to happen again -- a storm of Irma's strength or greater. There's no question about it.

Most of the housing stock around Tampa Bay is just like Bradford’s, built below the current code and extremely vulnerable to hurricane-force winds.

How do you know that structure is actually going to hold up in those winds? You bring it to the "Wall of Wind" at Florida International University.

"Welcome to the hurricane capital of the United States, the state of Florida," said Erik Salna, the associate director and meteorologist at FIU's International Hurricane Research Center.

Using the "Wall of Wind," Salna has – at his fingertips – the world’s only machine that can create Category 5 hurricane force winds in a research environment.

The FIU Engineering School constantly gets requests from both national and international companies and organizations requesting testing for various building materials. Those materials come to South Florida to be put to the test.

"We’ve created a facility that can now create real hurricane conditions, which is so vital when it comes to research..." Salna said. "But, also, how can we build better, build stronger and make our homes and businesses stronger for the next hurricane?"

The wind codes are reviewed every three years, but that doesn’t mean changes are made every time. The last time the zones were changed was in 2010.

"When it comes to hurricanes, research is suggesting there will be more storms, stronger storms, so we can’t build to the past, we have to build for the possible future, moving forward," Salna said. "We have a long range of data that shows that we are the bullseye, we’re the peninsula that sticks out into Hurricane Alley.

"Of all states, we need to be the one to lead when it comes to wind engineering research and translate that to building codes because that’s our chief hazard."

And Florida has done that. The state's building codes are considered some of the strongest in the country by various research organizations, including the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety but as changes in our environment fuel bigger, stronger storms, our codes will be tested.

"I don’t think we’re debating climate change anymore, I think the debate needs to move to, 'Can we adapt?'" Fugate said.

Before serving as the former head of FEMA, Fugate was Director of Emergency Management for the state of Florida.

"We’ve got to embrace the fact that we’re a hurricane-prone state," he said. "The problem is, if our building codes and practices are based upon historical events and not what could be occurring, we tend to build below the design requirements to survive these storms."

Should Florida have a uniform wind code?

"Well, that’s now the big question. That’s now the big discussion," Salna said. "Everybody needs to seriously sit down and talk about that and realize and understand that change may be needed here on how we adjust the building code across the entire state."

One thing we do know: Newer homes built above the current code held up extremely well in recent storms, even in some of the hardest-hit areas.

"We saw examples of homes that were built above the code. We saw that in the Keys from Irma and we saw that in the panhandle from Michael," Selna said. "We saw how some buildings withstood the wind, they were newer and built higher than the code demanded."

Fugate adds: "You should really think of the building code as the minimum you’re building to, and if you’re in a coastal area or an area subject to these storms, you probably want to think about building even to higher standards."

About that standard code, again: The current wind zones are configured, in part, based on past storms. Fugate says that is not the best practice.

"Looking at past data to determine our vulnerabilities and risk isn’t working, particularly for hurricanes," Fugate said. "There’s not any part of the coast of Florida that could not get hit with a major hurricane."

After Irma, Bradford was left to handle most of the repairs on her home by herself, and she has advice for anyone who thinks Florida’s wind codes are just unnecessary red tape.

"Be prepared. Don’t take anything lightly," Bradley said. "I would try to build above the codes if I had to build another house. I would try to build above the codes."

Photos of Hurricane Irma damage and destruction

The Florida Building Commission oversees reviewing the building codes and is currently in the process of reviewing data collected after Hurricane Michael. Those results will be released in June.

The real power for change lies in the hands of our state leaders, who say this issue has not even come up for discussion in the last session, which ended May 3.

A hurricane is coming. What about my house? Mitigation costs money. Is it worth the price? Depends on who you ask.

Most experts will tell you: Hurricane Andrew was the storm that changed everything.

- Kevin Robles, COO of Domain Homes: "I think you have to go back to Hurricane Andrew to really understand the evolution of the hurricane codes or the Florida Building Code."

- Marvin Dryden, city of Tampa: "Hurricane Andrew taught us a lot of things."

- Erik Salna, "Wall of Wind": "Hurricane Andrew – that was a game changer that woke up Florida, made everyone remember again we live in the hurricane capital of the United States."

In the aftermath of Andrew, Florida adopted some of the strongest building codes in the country, but some critics say those codes are not strong enough because they haven’t evolved with the changing climate.

"After Hurricane Andrew in 1992 as it made landfall in Homestead at about 145 mph, there were many, many catastrophic loses," Robles said.

Robles builds homes throughout the Tampa Bay area.

"When they went back and forensically looked, what they found out was that the houses became disassembled during the wind event of the hurricane," he said.

That’s when it dawned on state leaders: Stronger building standards guarantee stronger built homes, limiting the amount of catastrophic damage in major hurricanes. For instance, think about Hurricane Michael last year when it hit the panhandle.

"The major devastation that you saw was because you had homes that were 40, 50, 60 years old in that area. They were built under the early codes or frankly no codes," State Sen. Jeff Brandes (R) said.

Wind zones finally were implemented in 1995 following Hurricane Andrew, which destroyed more than 63,500 structures and caused $27.4 billion in damage.

Brandes has concerns about what could happen in Pinellas County if a storm like Michael were to hit, but he also has concerns about the cost associated with stronger building codes.

"The thing that you want is at least a minimum wind code across the entire state, but also you need to be thinking about the cost of insurance for new buildings and how much it’s going to cost to rebuild to the current codes and how overall that will impact insurance pricing in the region," Brandes said. "There’s not a hard and fast science to this issue. There is a little bit of science and a lot of art to figuring out what the building codes should be at any given community.

"It’s really easy to say go to the max, everywhere in the state of Florida should be Miami-Dade but what you don’t realize is you won’t have anybody living there then because people in Bay County can’t afford to build under the Miami building codes."

Remember: Brandes is a politician. Ask someone in the science community and those added building costs make a lot more sense. To them, it's basically the old "ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure" philosophy.

"For every one dollar we spend on mitigation, we save six dollars in damage and clean up. Financially that’s a no brainer," Salna said. "We’re the ones that handoff that baton to the next generation and what’s that infrastructure world that they’re going to live in?"

Darryl Rouson, a Democrat, is one of Brandes’ colleagues in the state Senate. Despite their party differences, both agree that strengthening building codes would cost Floridians more money.

"I’m a little surprised that there is nothing moving through the legislature right now that would address building codes," Rouson said. "Statewide, we need to look at this. We can’t mandate a statewide standard because of urban versus rural, coastal versus inland.

"It’s difficult to mandate a statewide standard but we can encourage each jurisdiction, each county, each region to take a look at itself and come up with something better."

When it comes to building codes, money is always a factor. According to Fugate, Florida lawmakers nearly did away with the entire process of reviewing wind zones, in part, because of the cost.

"In 2017, members of the Legislature lobbied by those groups that were interested in changing that initially attempted to stop the updates completely," Fugate said. "They said it was overly burdensome, it was red tape, some of these codes weren’t applicable to Florida, we were making homes unaffordable."

Hear from the builder.

"You’re going to reach to a certain point that’s good enough for now unless there’s additional innovations or building sciences that finds a way to make it more fortified for less money," Robles said. "There’s also an affordable housing crisis as well. As a builder, you’re always trying to hit a balance.

"We can make almost anything; can anybody afford to have that?"

And while both parties may agree on the issue of cost – the issue of climate change remains a point of contention.

"Climate change is real, and we need to face it. Both sides are going to be forced to come together by the calamities, by the catastrophes and work towards a solution that involves recognizing there is global warming, recognizing there is climate change," Rouson said. "What can we do now so that our children and grandchildren are left an environment and a future on this beautiful planet earth that we’re enjoying right now?"

"It’s one of these areas where let’s put the experts in the room, get the best advice we can get and if we need to make adjustments, we can do that," Brandes said.