Saving our Springs: How pollution, pumping and people are destroying Florida's freshwater treasures

Florida has the highest concentration of freshwater springs in the entire world, but the crystal-clear oases are at risk.

On an early summer morning in Gilchrist County, Bob Knight and Merrillee Malwitz-Jipson took a leisurely paddle along the Santa Fe River.

"This has been called the last pristine river in Florida because there's no wastewater treatment plants discharging into this river. There's no pipes withdrawing water directly from this river,” said Knight, the executive director of the Florida Springs Institute. “But it's not healthy because of the things that are happening around the river."

More than 36 springs feed the Santa Fe, but many of them are polluted and have reduced flows.

"The springs are being loved to death," Malwitz-Jipson said.

Ground pollution from nitrates, groundwater pumping by cities and businesses, and excessive recreation are the three main causes of impairment and decline in Florida’s freshwater springs.

Knight warns if nothing is done, healthy springs could vanish.

Pollution problems Water looks clear, but it's not pure.

Rum Island Spring is one of more than 36 that feed the Santa Fe River.

“This is classified as an impaired spring by the state because of the nitrate concentrations,” Knight said.

Just a little farther down the river at Gilchrist Blue, the beauty abounds, but the pollution is even worse.

"Nitrate is chronically toxic to humans. It's acutely toxic when it's in high enough concentrations, so this is the same water that we drink, and we should be worried about that,” he said.

While many see spring water as one of the purest forms of H20, Knight says that’s not the case.

“Well, our groundwater is supposed to be, and springs, that's all they have is groundwater. But no, we've contaminated...our groundwater to levels that are said to be safe to drink by our public health departments, but are anywhere from 20 to 100 times higher than the natural levels of nitrogen in our natural groundwater, our unpolluted groundwater,” Knight said.

Fertilizers from agriculture and septic tanks are a major source of these nitrates.

Two hours away from the Santa Fe where the Weeki Wachee River glistens a glowing green, its namesake spring pumps out more than 170 million gallons of water a day.

Thousands of people take in this beauty every year. However, the nitrates have polluted the water in this spring, as well.

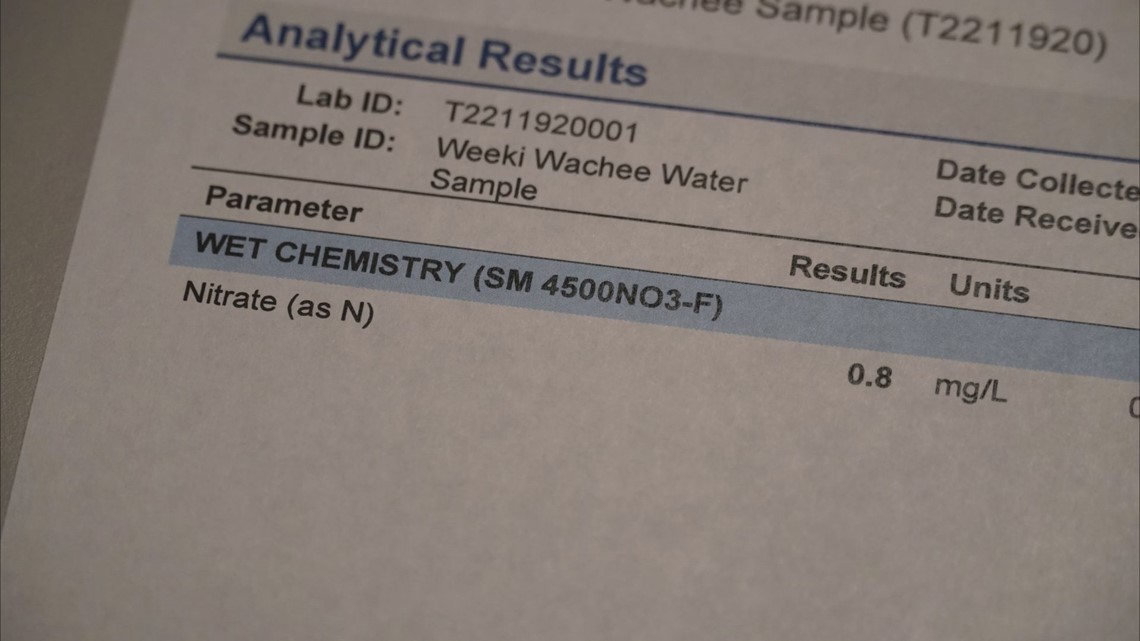

Testing the springs Results show increased nitrates in the water.

10 Investigates took samples from the spring and got an independent test from Advanced Environmental Laboratories in Tampa.

"The springs seem to be going up. It's because of the urban agriculture. Florida's growing so fast, right? And when the urban development encroaches around that area, then those natural areas that would filter the water before it made it down to the springs, that's gone. So that's kind of disappearing,” said Michael Cammarata of AEL. “Plus you have agricultural livestock, and septic tanks.

"So, all those things together, we're kind of seeing an increase in the spring. And I don't know if it's going to go down because Florida is a growing state."

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection, or DEP, set a limit for nitrates of point 35 milligrams per liter. Our testing of the Weeki Wachee Spring came back at 0.8 mg/L — that's more than twice the limit of 0.35 mg/L.

10 Investigates also tested the water at Rum Island Spring where we first started. Those results came back at 1.95 mg/L — more than five times the limit.

Knight says it's even higher at Gilchrist Blue.

"It's actually at a concentration that's high enough to cause illness in humans, and possibly even cancer. Nitrate is chronically toxic to people,” he said, adding that people swimming are not in danger, but drinking the water on a consistent basis could cause harm.

It raises a question: What is being done to address the pollution?

Protecting the springs DEP isn't following rules as intended, says former lawmaker who championed law.

"We have strong laws that are not being enforced,” Knight said.

In 2016, the legislature passed the Springs and Aquifer Protection Act to address excessive groundwater pumping and sources of nitrogen pollution. Lawmakers left the Department of Environmental Protection in charge.

The department's "Basin Management Action Plans," or BMAPs, are roadmaps for cleaning pollution, but Knight says DEP isn't doing enough.

"Their plans don't work. And they know that. They know that. They've been told, they've been shown the data and the public has tried to do something about it, but unsuccessfully. It's very difficult to fight your state,” Knight said.

Some groups are trying. The Florida Springs Council, the Sierra Club and other environmental groups across the state are now challenging DEP on this law, also saying the state's plan to clean up polluted springs within 20 years doesn't work.

“They're very far short. They're very far short,” said attorney John Thomas during June oral arguments in the Florida First District Court of Appeal. He's representing the Sierra Club and other environmental groups, including Save the Manatee Club, Silver Springs Alliance, Rainbow River Conservation, Our Santa Fe River and the Ichetucknee Alliance. “BMAPs are not just aspirational...those things are enforceable.”

The DEP has pushed back against this argument.

“The petitioners in this case have a strong belief as to what the law ought to be and what the law ought to require the department to do with an action basin management plan, but that's not what the law is,” Jeffrey Brown, an attorney for the DEP, said in response.

But those who came up with the law disagree.

David Simmons was a Republican senator representing District 9. He's one of the lawmakers behind the 2016 Springs and Aquifer Protection Act. He says DEP is not following the law the way he and his co-sponsors intended.

"Is the DEP right now breaking the law?" asked 10 Investigates’ Emerald Morrow.

"I don't believe that the DEP right now has followed through on the directive of the Florida Legislature. And that's a simple fact,” he said.

Under the law, DEP is supposed to make sure when cities and companies pump from the aquifer, it doesn't cause any harm. But Simmons says the department hasn't properly defined what harm is.

"The language that I saw that they have been using for the last six years is not the appropriate language and it's not in accordance with the directive that was given,” Simmons said.

Simmons says he's been meeting with the DEP and just submitted a new set of proposed rules for defining harm to better protect our water resources.

"You cannot withdraw so much water that it is going to be not replenished,” he said. "Water is a treasure for Florida. We have a lot of it.

"We need to make sure that it's clean, and that we preserve it and that in fact, it is here for ourselves and for our children and our grandchildren."