Inside Florida's voter fraud arrests — and the system that allowed them to happen

"In order to be convicted of voter fraud, you have to have intent to commit fraud, and I had no intent to commit it whatsoever," Nathan Hart said.

AUGUST 18

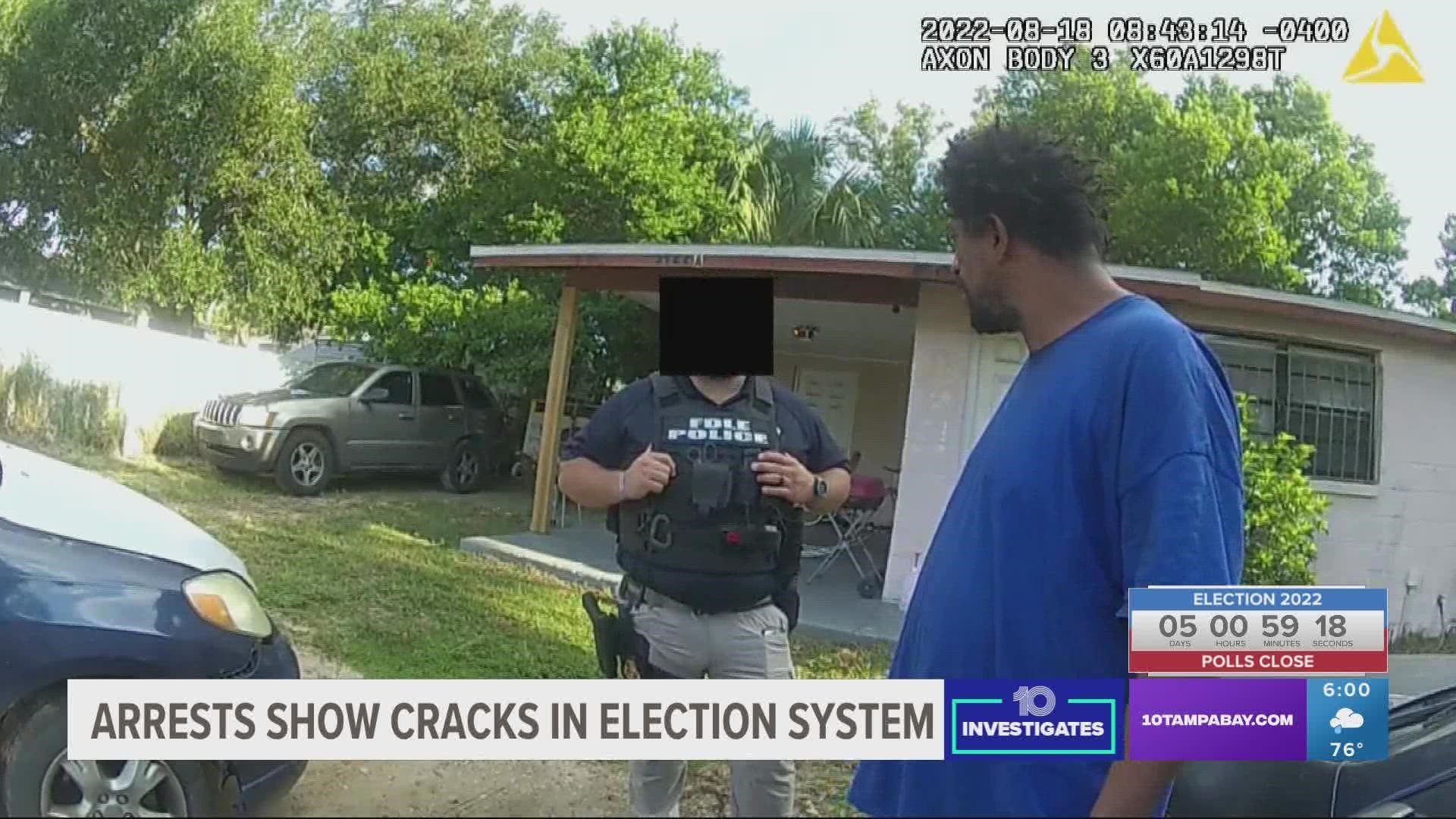

For Nathan Hart, Aug. 18 felt like a nightmare.

“When it initially happened, I just felt numb,” he said.

That morning, a Hillsborough County deputy showed up at his Gibsonton home to execute an arrest warrant. Hart faced false swearing and voter fraud charges for voting in the 2020 election as a convicted felon.

A bewildered Hart explained to the deputy how he received a voter registration card from the state after a canvasser encouraged him to apply, which led him to believe he could exercise his right to vote. The deputy listened and he had a valid defense. He then took Hart to jail.

Hart was one of 20 convicted murderers and sex offenders arrested that day under the state’s new Election Crimes and Security Unit. Six of those arrested live in Hillsborough County.

Gov. Ron DeSantis held a press conference hours after Hart’s arrest to make the announcement.

RELATED: Hillsborough court cases begin for those accused of illegally voting in 2020 election

“These folks voted illegally, in this case, and there's gonna be other grounds for other prosecutions in the future,” DeSantis said in Fort Lauderdale. “They are disqualified from voting because they have been convicted of either murder or sexual assault. And they do not have the right to vote. They have been disenfranchised under Florida law.”

A conviction could mean another felony, up to five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. It’s a price Hart says he cannot afford to pay.

"If the governor himself has got it out for me, he wants to crucify me. Then what chance does a lowly schmuck like me have to really do much about it?” Hart said. “'Cause I mean, I'm nobody. I'm poor, I have no clout anywhere whatsoever."

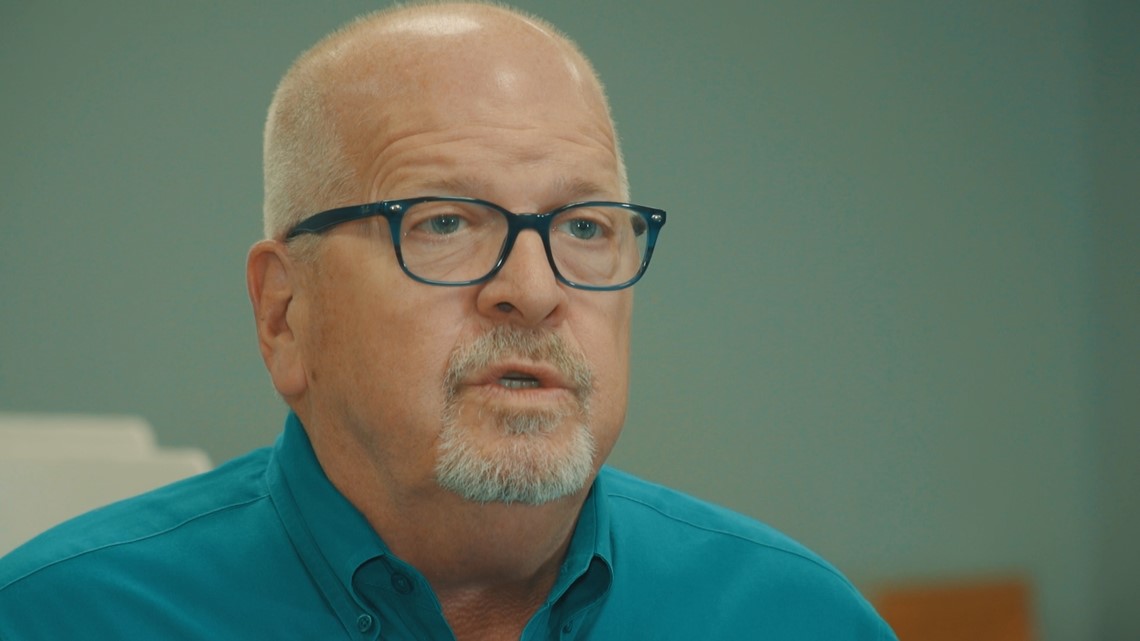

Hillsborough County Supervisor of Elections Craig Latimer says even with more attention on the issue of voter fraud, it is not a widespread problem. He said the few cases he has seen would not be enough to impact the outcome of any election.

"I think, in five years, I've turned over 14 cases to law enforcement," he said. "You're not going to have anything widespread for the mere fact that you know, we've got we've got really good voter rolls, number one."

Of the six arrests in Hillsborough County, videos 10 Investigates got through public records requests show most in a state of frustration and confoundment.

“Y’all said anybody with a felony could vote,” Tony Patterson could be heard saying on a bodycam recording as he was being taken into custody. “What you mean, I couldn’t vote? I don’t know this. How I’m supposed to know I can’t vote, man? And why y’all doing this now?”

Records from the Hillsborough County Supervisor of Elections show Patterson, a convicted sex offender, registered to vote in 2008. He registered again in 2019 after voters passed Amendment 4 the previous year.

When Amendment 4 took effect in 2019, the state restored the right to vote to Floridians with felony convictions – except to those with murder or sex offense convictions. Additional legislation also required all fines and fees to be paid before voting rights.

That fine print has is not always easy for people to understand, says criminal defense attorney and former prosecutor Lucas Fleming.

"It's really confusing for folks to know if they're eligible to vote or not..."I mean, even as a lawyer...I read this stuff going back gosh...this is a lot, right, to understand and to try to figure out," Fleming said. "Their belief in their own mind is that, 'yes, I did my time, I'm out of jail, off probation, I should be able to get my rights restored automatically."

LEGAL LOOPHOLES

On March 3, 2020, Hart headed to the Ruskin DMV. He can’t remember if he was renewing his driver’s license or his registration, but he remembers what happened right outside of the building.

“There was a guy out in front that had a table set up with all the signs and banners. ‘Register to vote,’ you know, ‘Get out the vote,’ you know, that kind of thing,” he said. “And before I went in, he asked me if I was able to vote.”

Hart told him no.

“I’m a convicted felon,” he said. “I’m an ex-con, I can’t.”

Hart says the person insisted.

“He said, 'Well, there’s this law passed you know, two years ago, that says ex-cons who complete their sentences can vote,” Hart said. "I’m like, ‘Well, alright, what the hell.' So, I just went ahead and filled out the form like he showed me, and a month later, I got a voter ID card. So, I figured, I guess that law applied to me after all."

Hart shared this story with a deputy handling his arrest. That deputy offered this advice: “There’s your defense. You know what I’m saying? Sounds like a loophole to me,” the unidentified deputy said.

Some voting rights advocates say agree.

"The system's broken on the front end,” said Neil Volz, deputy director of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition. "If like in other states, we had an immediate verification process, then none of this would have happened. Nobody would have been arrested, we wouldn't have had to spend all this money on law enforcement and the courts and seeing the pain of our own fellow citizens going through this process."

Florida law requires the state to tell local elections offices who can’t vote because of certain felony convictions.

“They notify us of somebody that has an adjudication of guilt,” said Hillsborough County Supervisor of Elections Craig Latimer. “When they do that, they forward a file to us. And it has, for instance, information from the clerk's office, or from the Florida Crime Information Center from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement – things that I don't have access to.”

However, 10 Investigates found the state did not tell the Hillsborough County Supervisor of Elections that those arrested for voter fraud could not vote until at least a year after they cast ballots in the 2020 election. In some cases, it took nearly 18 months.

For example, the state did not tell Latimer's office to remove Hart from the voter rolls until January 2022. That's nearly two years after he registered.

Peter Antonacci, who led the Office of Election Crimes and Security before passing of a heart attack, sent a letter the day of the arrests saying Latimer’s office was not to blame for the voting errors.

"Through no fault of your own, records demonstrate that the convicted felons listed in the attached Exhibit A were registered to vote and voted in your county during the 2020 General Election," the letter reads.

The Department of State’s office places blame on the voters for their arrests. Spokesperson Mark Ard sent the following statement to 10 Investigates:

“The individuals who were arrested for election crimes are felons convicted of murder or sexual offenses who are, by virtue of their crimes, ineligible to vote absent clemency. The ultimate responsibility to ensure compliance with the law lies with the voter, as local and state election officials are obliged to take the word of the voter on the voter application – affirmations made under penalty of perjury.

This includes marking a box affirming that “the applicant has not been convicted of a felony, or that, if convicted, has had his or her voting rights restored.” At this point, by law, the local supervisor’s office must send voting information and voter registration documents to the applicant as a standard procedure in response to the voter’s testament of eligibility. This action does not indicate permission to vote for an individual who has obtained a voter card under false pretenses.”

10 Investigates pulled voter registration cards for all six people arrested in Hillsborough County. Most did check the box affirming that they have been convicted of a felony and that their rights have been restored.

The Department of State says this is perjury.

Those who worked on legislation to restore voting rights in 2019 to those with felony convictions under Amendment 4 say this isn’t how the law should work.

“I'm somebody who believes that the state should always be leaning towards grace,” said Brandes, R-St. Petersburg. “We should always be trying to restore people. And especially when people have paid their debt to society.”

Brandes says the Secretary of State needs to bear more burden in the arrests.

“The Secretary of State needs to take responsibility for what is happening, and they need to say we’re going to put the resources to ensure this never happens again,” Brandes said. “I think what you're seeing here is, across the state, people recognize the fundamental unfairness of these arrests. And they're going to recognize that the state has to do a better job of securing the voter rolls. But it's ultimately the secretary's responsibility as the defender of the voter rolls.”

SAVING THE SYSTEM

Voting is often called the cornerstone of democracy. Volz says the state should invest in a more robust system to better determine voter eligibility and protect election integrity.

“Other states do this. This is the information challenge we should all roll up our sleeves, get in the same room and figure this out, right? It’s so much better to fund on the front end and get the system operating with integrity so we don’t have arrests on the back end,” Volz said.

The cost to fix flaws in Florida’s election system could be exorbitant. But Brandes says the state must start somewhere.

“Simplify it only on a go-forward basis,” he said. “If you had a prior conviction, you know, it would cost literally tens of millions of dollars to go back and put all this microfiche in and clean up all these records and everything else like that. But it would be very simple to go forward with a better accounting software so we can determine what people owe and what they need to do to complete all terms of their sentence and make that publicly available for people to access.”

PROVING INTENT

When it comes to prosecuting the 20 statewide voter fraud arrests, Brandes says the intent is key.

“The way that we drafted the law was to say that if you were going to be arrested for [voting], the state had to prove that you did it willingly. Willingly means you had either knowledge or intent,” Brandes said. “What we found with these videos, I think so far, every single case of the 20 individuals is that none of them has said, I intended to do this, right?”

Brandes contrasted these arrests with others that happened in The Villages, where some admitted to voting twice in the 2020 presidential election.

"What you see with the arrests that occurred in The Villages is those people had both knowledge and intent. They knew they'd voted multiple times. They intended to vote multiple times," he said. "That's very different than somebody who has been out of prison for 20 years, who goes and fills out a voter registration card, gets a voter ID card back and only votes once, and had no knowledge and no intent to commit fraud."

An outspoken critic of the recent arrests, Brandes says he's received support for denouncing the state's actions.

"I think what people realize is that an overwhelming majority of Floridians supported Amendment 4. And I actually haven't received any pushback and frankly, largely support for my pushback against the voter arrests," he said. "The more I talk about it, the more it's discussed and the more people find out, the more this feels like these were political arrests and not proper arrests."

Attorney Lucas Fleming says the state could have a hard time prosecuting these cases in court.

"I think it'd be really hard for the government to prove that intent, that they specifically intended to defraud the government to get a voter card,” he said. “Frankly, I think a jury would have a hard time convicting somebody who basically was under the belief and understanding that their rights were restored…Good Lord, they just probably got out of prison or probation. Do you think they really want to go back and be charged with another felony for exercising the right to vote?”

For Hart, he says that answer is no.

"In order to be convicted of voter fraud, you have to have intent to commit fraud, and I had no intent to commit it whatsoever," said Hart. "If I had any clues it'd come and bite me in the behind, then I would've never stepped out my front door to go vote in the first place."

Hart’s case is one of six currently moving through Hillsborough County court. A judge in Miami recently dismissed one of the voter fraud cases there. The state says it plans to appeal.

Emerald Morrow is an investigative reporter with 10 Tampa Bay. Like her on Facebook and follow her on Twitter. You can also email her at emorrow@10tampabay.com.