TAMPA, Fla — While the world has been consumed by the coronavirus pandemic, other dangerous infections have quietly continued to take their own tolls.

We know there are sharks, jellyfish, stingrays, all sorts of predators that we look out for while in the water. But there's something else lurking below that is even deadlier than all three combined.

It's something you cannot see and have maybe never even heard of.

And that's a problem.

For nearly a year now, 10 Investigates' Jennifer Titus has been researching this deadly "Bacteria Below."

"He was a great guy. He's just genuinely fun to be around and always made you feel good, always," said Cheryl Wiygul, fighting back tears as she described her father, David Bennett.

David Bennett

It's been a year since David passed away in a Tennessee hospital after a family trip to Florida for the Fourth of July.

"We all went to a Rocky Bayou State Park with our jet skis and packed a picnic lunch. Jet ski and swam out there for like three or four hours," Cheryl explained to 10 Investigates' Jennifer Titus.

Hours later, David would wake up in pain.

He had lymphoma so the family thought the pain could be linked to complications from that. Instead of getting checked out in a Florida hospital, he and his wife drove back to their hometown in Tennessee.

"They ended up going straight to the hospital because he felt worse and worse and worse," Cheryl explained.

"They took off his shirt to put his gown on. He had a huge space about this big. My mom describes it as like a shelf of flesh that was turning black. She sent me the picture and I said that's flesh eating bacteria. Tell them he's been in the water," Cheryl said.

David died the next day.

"It wasn't until after that, his doctor followed up with the records and said that he had Vibrio vulnificus bacteria. That's caused him to go septic," explained Cheryl.

"It seems like an eternity and just like yesterday at the same time."

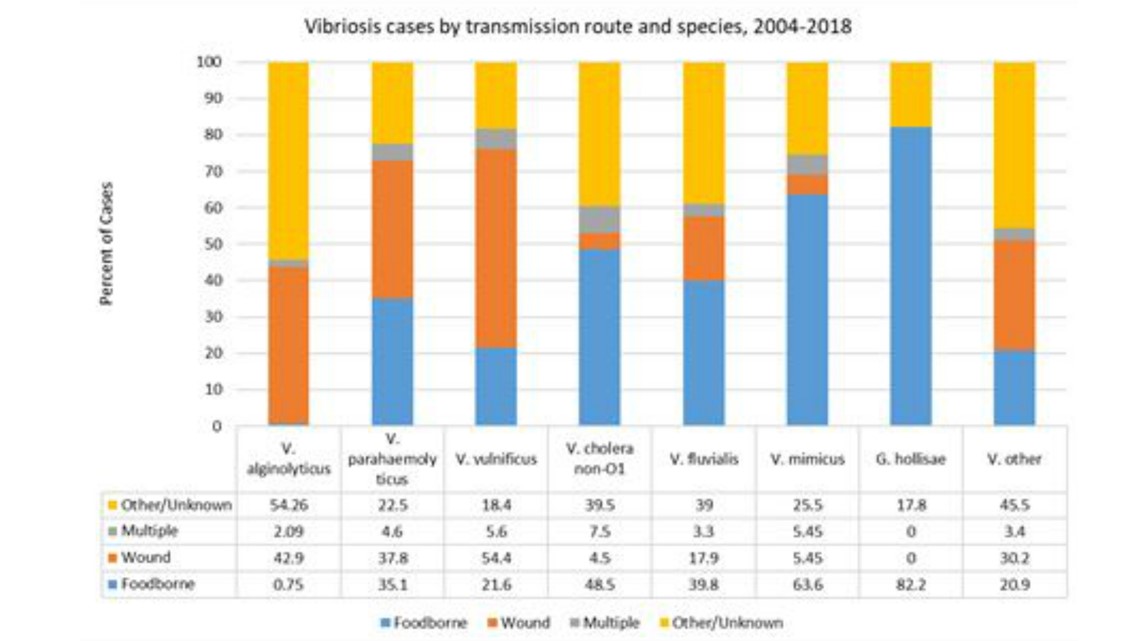

Vibrio vulnificus is a bacteria that lives in warm brackish sea water, like the Gulf of Mexico. You can contract the bacteria one of two ways: through a cut or by eating raw shellfish. Some like to call it "flesh eating bacteria" because some cases turn into necrotizing fasciitis, which looks like the flesh is being eaten away.

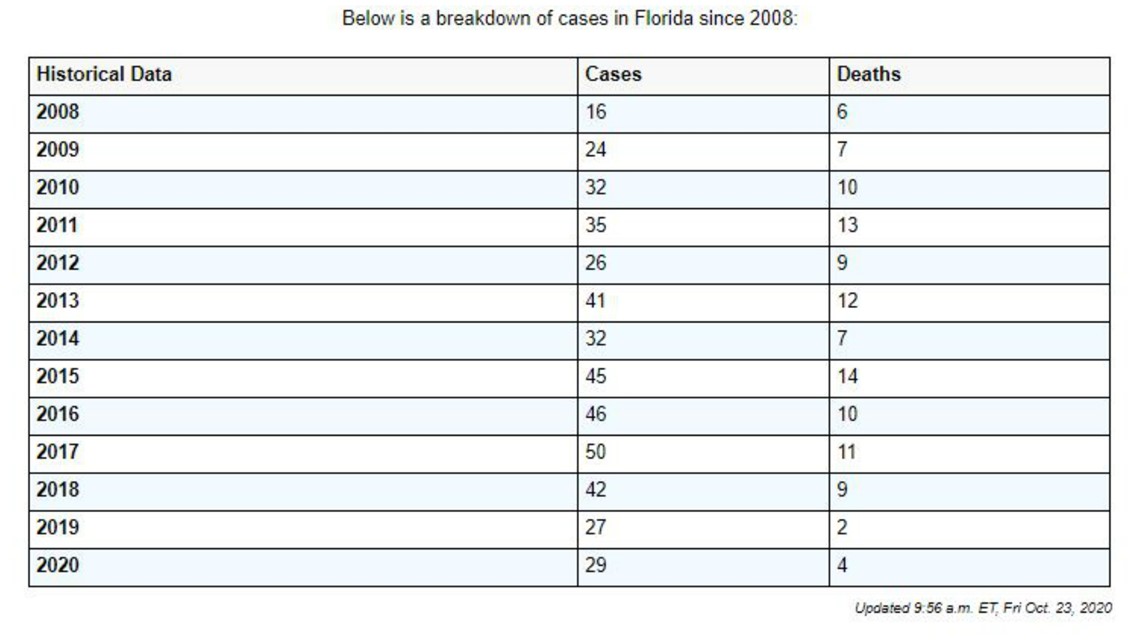

According to data from the Florida Department of Health there have been 420 cases of vibrio vulnificus in Florida since 2008.

The year 2019 accounted for 27 of those cases. But when it comes to Cheryl's dad, he's not part of these statistics. It's because of how the department tracks the cases. Since David died in a Tennessee hospital, his case was sent over to the Tennessee Department of Health, not Florida's.

"I find that to be a problem," said Cheryl.

After discovering her dad's case was not being tracked in Florida, she sent a letter to the Tennessee Department of Health asking why.

In an email from the Tennessee Department of Health, an official told Cheryl "For infections, those events are always registered in the state of residence for someone who has a reportable condition, regardless of where the exposures happen."

Cheryl says that makes her uneasy.

"I feel like there's not an accurate picture out there and it makes people feel too comfortable with it. And it's not to scare people. It's just to keep people that are at risk from dying and There's nothing wrong with that," said Cheryl.

Carolyn Fleming

And, Cheryl isn't alone.

"You know, everybody loved her," said Wade Fleming as he described his mother, Carolyn Fleming, to 10 Investigates' Jennifer Titus.

"The doctor called me and was very polite, but he was very concerning about her health. He's like, this is serious," Wade said. "He says she has necrotizing fasciitis."

For Wade, words like necrotizing fasciitis were new to him. Until last summer.

"My mom, typical, put down her chair and said I'll see you in 15 to 20. She'd take a walk in the beach," explained Wade.

During that walk, she cut her shin on a gully on the beach where the water had washed out some of the sand on shore.

"Just then, the lifeguard came by and his little ATV or whatever, and we whistled at him, he came over and rendered first aid. You know, put some antibiotic cream on it, bandaged it up, wrapped it up, cleaned it up, you know, and just said, you got to be careful and, you know, have a nice day," Wade explained.

Within two weeks, Carolyn Fleming passed away.

"You know, if I had known that, you know, it was something so severe, we would have stayed. But again, there were no signs, no, no warnings, no signs," explained Wade of his mom's condition.

Dr. Afsar Ali is a research professor at the University of Florida.

"It is more prevalent in the United States," Dr. Ali said. "It has increased significantly since 2010 until the present time. Because our water is getting warmer."

For his entire 34-year career, Dr. Ali has been studying vibrios.

"Do you think there's enough research, enough studies happening so we can really get a good grip on how prevalent this is in our ocean waters here in Florida?" 10 Investigates' Jennifer Titus asked Dr. Ali on a video call.

"No, my sense is that since there are only 100 cases of the vibros in the entire United States with 20 to 30 deaths per year, it gets less attention from the state as well as the federal government but if you look at the deaths, that 25 percent to 30 percent of the people die, it's a significant portion of the people that are dying from the disease," explained Dr. Ali.

Dr. Ali says people with underlying conditions need to be very concerned and made aware of this deadly bacteria.

"It is definitely going to be a public health threat. The reason is, particularly in Florida, that we depend on the tourism and our population, almost 20 percent to 25 percent population is 65 and over," said Dr. Ali.

"So, more research and more education is key?" asked Titus.

"Absolutely," Dr. Ali answered. "So it is, as I said, I mean, it is a rare case, this deadly flesh, eating bacteria, for underlying people, but it is not a small thing because a life is a life."

And, that is exactly the point that Cheryl and Wade think needs to be made.

"I just I want everybody to know and understand it. Because I don't want anybody to go through this, I want any I don't want anybody else to lose their loved one after having fun on vacation just because they didn't know," said Cheryl.

Both families are pushing for change when it comes to educating people about vibrio vulnificus. They'd like to see signs up on beaches warning people with underlying conditions about the potential for deadly bacteria. Cheryl has even started a petition pushing for these signs.

You can see that petition here.

As we mentioned, this is a danger many of us don't think of when heading to the beach. So, how common is vibrio vulnificus?

In 2020, there have been 29 cases of vibrio vulnificus in Florida and four deaths.

Six of those cases were in the Tampa Bay area. Two of those cases ended in death: one in Hernando County and the other in Pasco County.

And, the number of cases statewide is up from 27 in 2019.

Remember these are only cases that were found in Florida residents.

As 10 Investigates uncovered, if someone from another state is visiting Florida and gets infected, that case counts in their home state. You can see the year-by-year data for yourself by clicking here.

MORE FROM 10 INVESTIGATES:

►Breaking alerts from 10 Investigates: Get the free 10 Tampa Bay app

►Dive deeper into stories! Sign up now for the Brightside Blend Newsletter