State to create 'Florida-specific' behavioral health survey for students: What this means

In the spring of 2022, the Florida Department of Education announced it would stop using the CDC survey to assess children's mental and behavioral health.

Mental health in kids is declining. It's something we've heard in recent years as the pandemic took a toll on children in and out of the classroom.

But what does that really look like here in Florida? Suicide is the second leading cause of death in adolescents.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers a survey to track behavioral health trends, called the Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

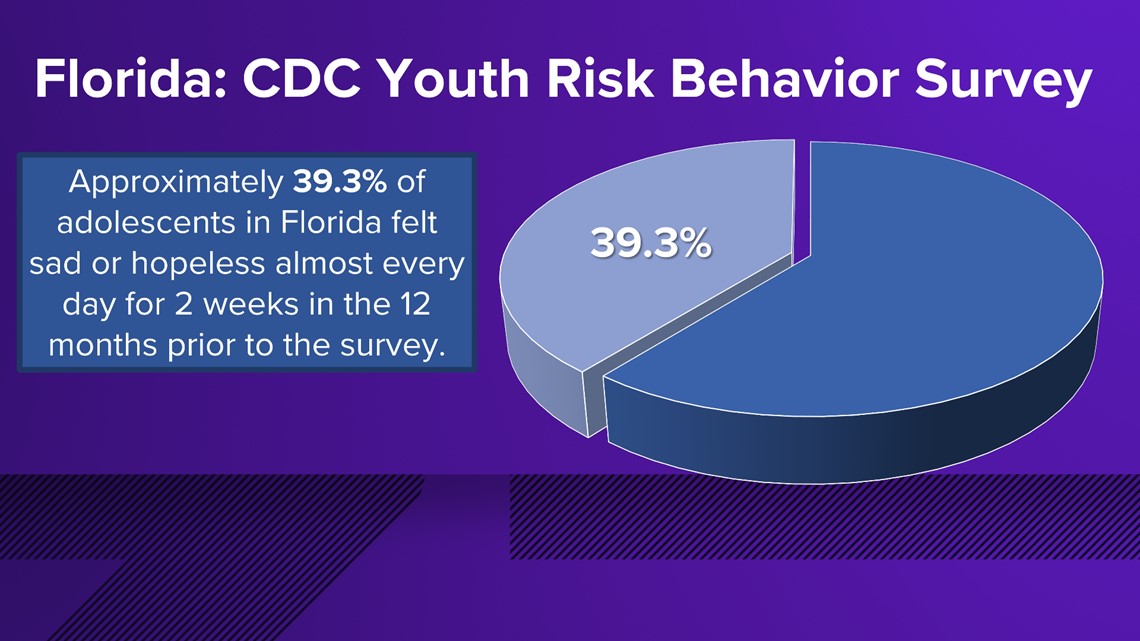

According to that survey, approximately 39.3 percent of adolescents in the state of Florida felt sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks in the 12 months prior to the 2019 survey.

Almost 18 percent of youth seriously considered attempting suicide and almost 9 percent of adolescents actually attempted suicide. In a high school of 2000 students, that translates to approximately 180 will have actually attempted suicide.

All of these statistics have worsened since the previous time the survey was administered in 2017.

Personal impacts What mental health struggles look like for a Florida family.

"It is a hard road when you do have a child that has a mental condition, and that has a disability. It is hard," Yanna Richardson said.

Hard. That's how Richardson, a Tampa mom, describes parenting a child with ADHD and sensory processing disorder.

Richardson's daughter, Zoè, is 9 years old. She was born prematurely.

"She was born a micro preemie – 1 pound, 3 ounces and at 26 weeks," Richardson explained. "So it's been a long road. But with that road, we have a little bit of mental challenges, and also disabilities," Richardson said.

Richardson said her daughter will have meltdowns and shows difficulty regulating her emotions. Thankfully for Zoè, she has a mom who had her diagnosed and treated. But it wasn't without some mental health stigmas to overcome.

"I know a lot of minorities, we have an issue with going out, seeking services, and asking for help," Richardson said. "Because we don't want our children labeled...and I'm guilty of that."

Richardson said, as a mom, she's had to have difficult conversations with her daughter. Zoè also has chronic lung disease, causing her to miss school on occasion.

"Mentally, it takes an impact on her because I hear those questions: Why am I not like the other kids?" Richardson said. "You know...I tell her, it's nothing wrong with you. It's just what's happening right now... All I can do is try to talk to her and find like different resources to help her along the way."

Yanna Richardson and her daughter, Zoè

Having information and tools to treat a diagnosis is key. Richardson said she is constantly researching and reading articles on how to help her daughter.

"As a mom having a child with a disability, and who does face mental and emotional challenges, sometimes you don't know what to do," Richardson said. "Sometimes you want to help, but you can't because you don't know where to go to ask for help."

Richardson said it's thanks to a supportive community, her own research, her faith in God and adaptive teaching methods her daughter continues to succeed. But she wants to see more information for parents to help address "invisible" disabilities in children, relating to mental health.

"You know, just don't feel that it might be some other child's issue, because you never know," Richardson said. "It can be your own kid that's struggling, that you don't see, you know, so have those conversations."

Tracking mental health On a national and state level, here's how it's done.

Every two years, the CDC updates its Youth Behavior Risk Survey to be administered to high school and middle school students. The survey is completed anonymously.

The survey covers a wide variety of behavioral health topics, covering safety, smoking, alcohol consumption, sexual behavior, gender identity, self-image, diet, social media use and more. It's a way for school districts to track trends, for states to compare to other states and to compare local trends to national ones.

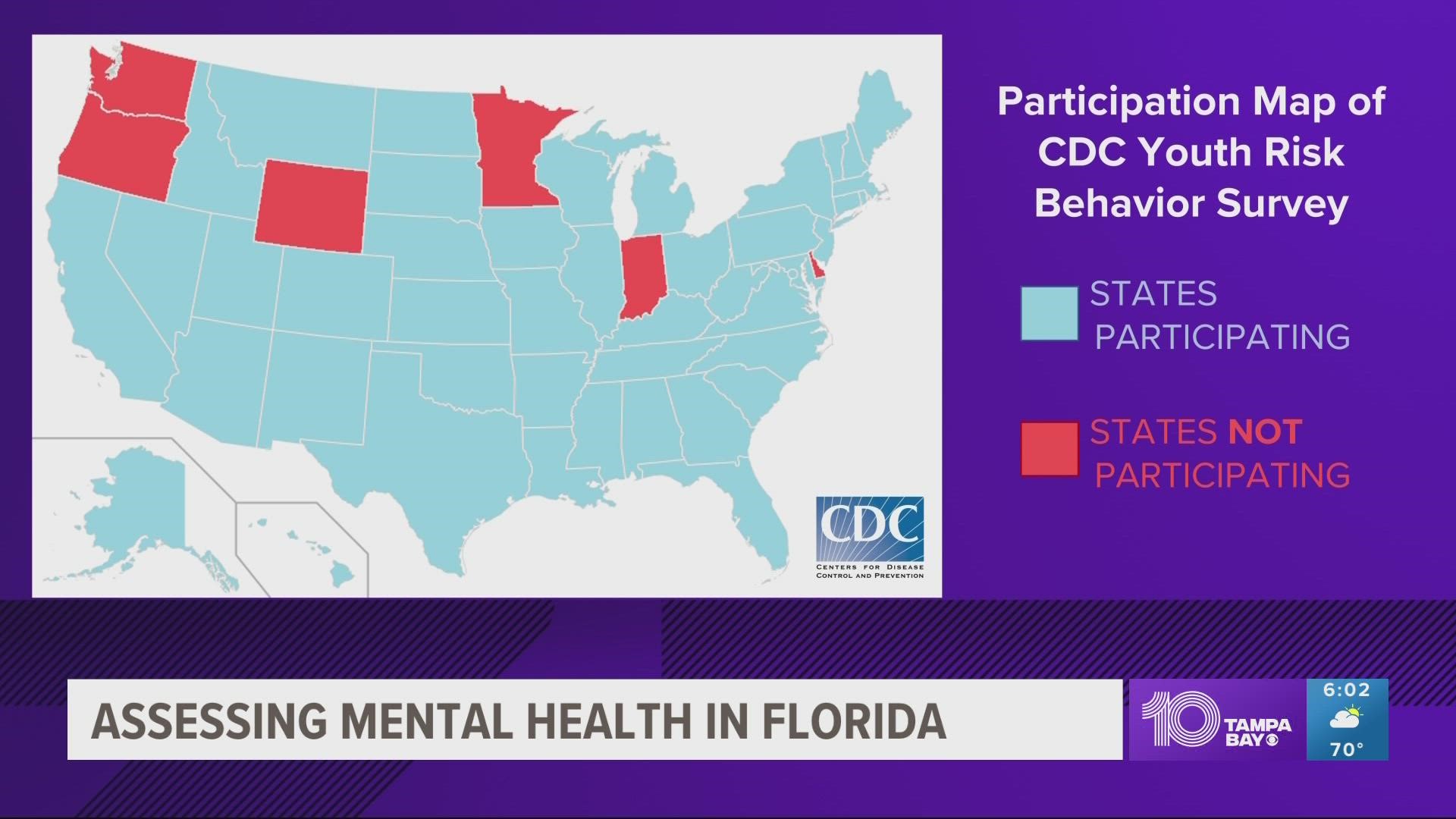

The most recent data shared from the survey is from 2019. Forty-four states, including Florida, participated.

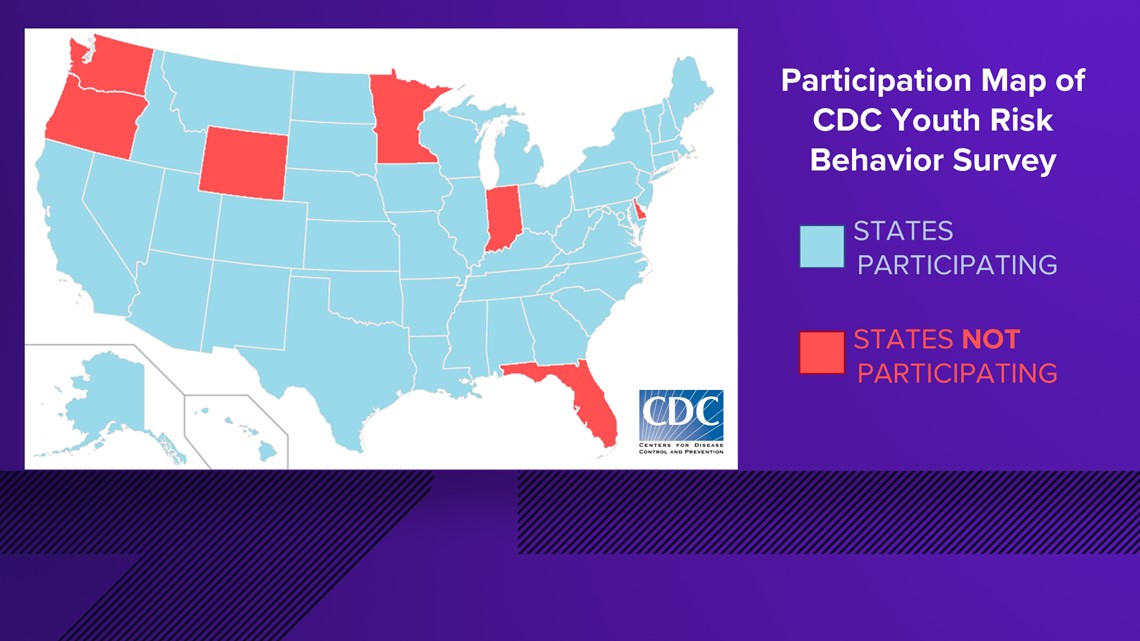

But in May of this year, the Florida Department of Education announced it would no longer administer the CDC survey to students. The DOE plans to make its own survey in its place.

The education department sent the following statement on why it made the move to create its own survey instead of continuing to administer the CDCs:

"The Florida Department of Education will administer a Florida-specific youth survey in 2023. Tailoring data collection to Florida’s unique needs allows for enhanced alignment within Florida’s resiliency and character education instruction and professional development initiatives for teachers in support of students, as well as to inform community-based resources.

"The Department distributed a memo to all superintendents on September 23 requesting their recommendations for workgroup members. These workgroup members will inform the process for the survey to be administered prior to the end of the school year. Relevant trend information from the previously administered survey will be maintained with the ability to tailor data collection to support the needs of Florida’s students. You can find a timeline for the new survey on our Student Support Services website."

10 Tampa Bay has been asking the Department of Education to clarify what a Florida-specific survey means for the last three weeks. At the time of this publication, our requests have gone unanswered.

Why does this matter? If specific questions aren't asked, certain trends cannot be tracked.

Dr. Angela Mann is an associate professor at the University of North Florida and the president of the Florida Association of School Psychologists. She pushed for state officials to keep giving students the CDC's Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

"We have students from historically marginalized populations or underrepresented groups, like our students who are identifying as LGBTQ, or students who are African American or black, were where we know that it's, it's often very difficult to actually gather data on how they're doing and what their well-being looks like," Mann said. "The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System is one of our only means of doing that."

With Florida now opted out of the survey, Mann said now Florida will not be able to compare trends with national or neighboring state trends.

"And so [the CDC survey] allows us to make very easy comparisons in terms of how our students are doing here in Florida relative to any other state in the country."

Florida is now one of seven states not participating. While the Department of Education said the goal is to make a Florida-specific survey, it's an option it had in customizing the CDC survey.

According to the CDC's website, "State and local agencies that conduct a YRBS can add or delete questions to meet their policy or programmatic needs. Specific guidance on the parameters that must be followed during questionnaire modification is provided to those agencies funded by CDC to conduct YRBS."

Mann said on top of the concern of Florida not collecting behavioral health data while it creates its own survey, the information shared by students in the survey can affect what mental health services a school offers.

"It's important for us to know trends about suicidality about risky behaviors they're engaging in right so that we can design interventions to support that," Mann said.

It's an issue Mann sees now, saying the number of school psychologists is far fewer than what is needed in Florida schools.

"So currently, we have one school psychologist in Florida on average serving close to 1,900 students, and that number has been increasing as of late," Mann said. "Then we have some school districts who have no school psychologist on staff at all. There are some school districts where the ratio of students being served by school psychologists is as high as 7,000 students."

The National Association of School Psychologists recommends school districts employ one school psychologist to cover 500 students.

"We're suffering from a critical shortage, even looking nationally, and at other states, other states are, their average ratio tends to be around one to 1,400 students," Mann said. "So, unfortunately, here in Florida, we are experiencing some really big caseloads, and it's having some negative impacts on students."

Now what? When will a 'Florida-specific' survey be ready?

The Florida Department of Education has created a workgroup composed of people meeting one of the following criteria:

- Hold a Florida Educator Certificate in K-12 Health, or PK-12 School Counseling, School Psychology, or School Social Work;

- Be a district Health Education, School Counseling, School Social Work or Mental Health Coordinator;

- Be a state agency or college/university representative; or

- Be a community partner lead, healthcare practitioner, or parent with a student at the secondary level.

The workgroup members selected will provide feedback for what goes into a Florida-specific youth survey.

In the winter of 2022, the survey will enter into the testing and refinement phase. The survey will then be administered to students for the first time in spring 2023.

And in the summer of 2023, the survey results will be compiled and analyzed, then published by the Florida Department of Education.

Malique Rankin is a general assignment reporter with 10 Tampa Bay. You can email her story ideas at mrankin@10tampabay.com and follow her Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram pages.