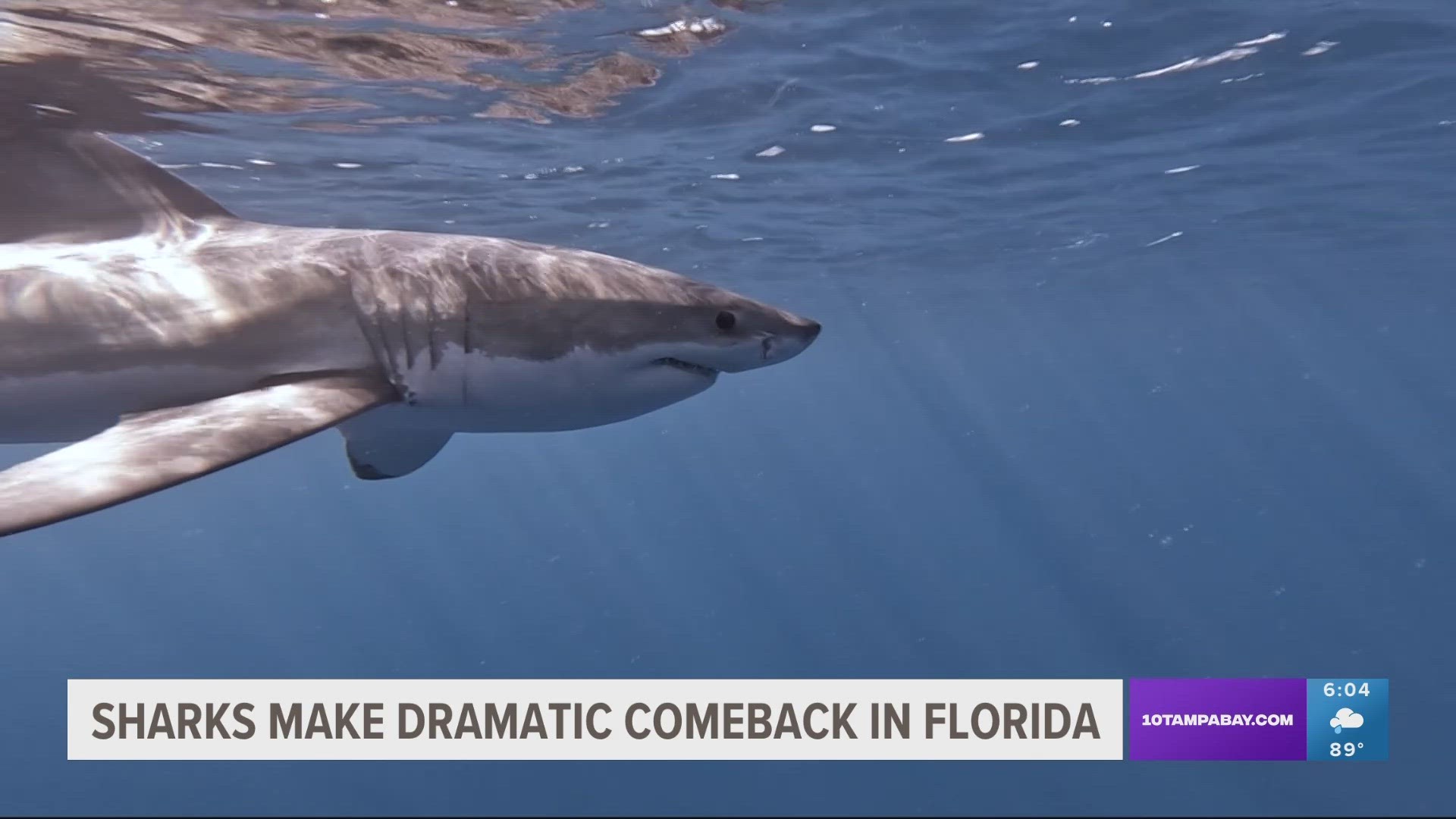

SARASOTA, Fla. — One of the most feared and misunderstood apex predators on the planet is making a remarkable return to the ocean, including the Gulf of Mexico.

Great white sharks have rebounded after a dramatic decline from overfishing, Ocearch has found. Marine biologists believe about half of the tens of thousands of great white sharks on the East Coast spend their winters in the Gulf of Mexico. They are the snowbirds of sharks.

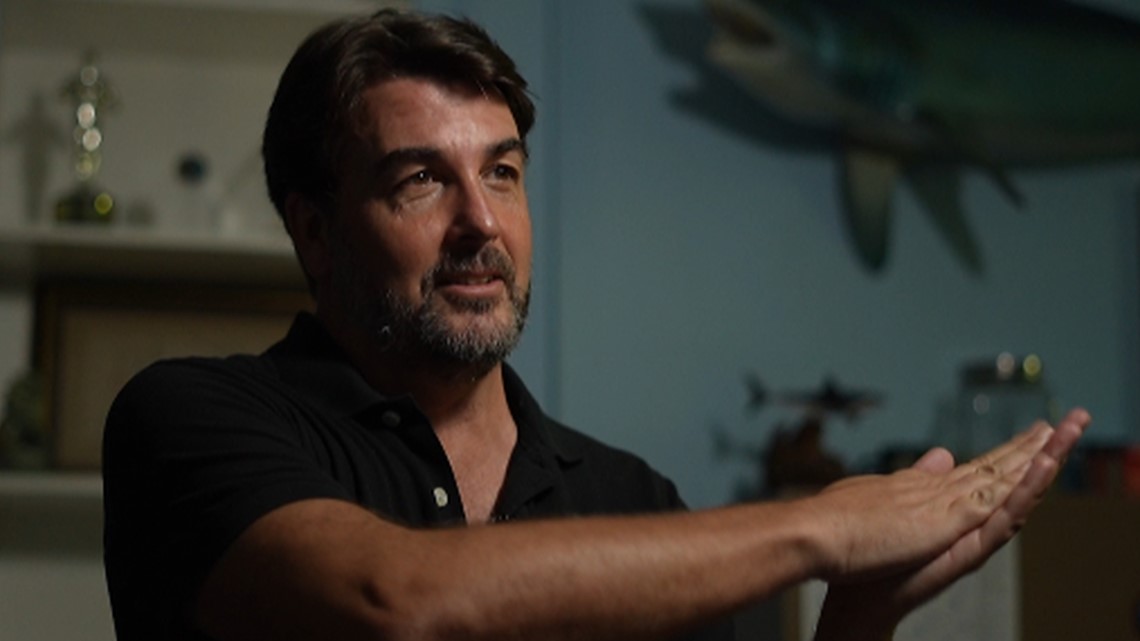

"And then they’ll leave, about the same time after Easter, and start heading north," Sarasota shark researcher Dr. Bob Hueter said.

Hueter is the chief scientist for Ocearch, a non-profit conducting unprecedented research on the ocean’s giants. For the past two weeks, Hueter and other Ocearch scientists captured great whites 1 mile off the coast of South Carolina.

"As humans, it was thrilling to see these animals swimming around us," Hueter said. "They are rebounding."

The Ocearch scientists run 25 different projects with every shark brought on board. In 15 to 20 minutes, the team works like a NASCAR pit crew.

"We’re collecting blood samples. We’re taking muscle samples," Hueter said. "Some of us are doing ultrasound to look for pregnancy and other things. We’re taking genetic samples. Of course, we’re measuring the animals, which is something that we can do very accurately on the lift that you can’t do in the water."

Before the sharks are released, they are tagged with GPS trackers. Their migration is tracked for years.

“Beyond where they were going and when, we didn’t know why and the tracking helps us determine why,” Hueter explained.

In 2021, Ocearch scientists attached a GPS tracker to a 12-foot, 3-inch great white, named "Scot." In two years, Scot has traveled 9,556 miles, spending last winter off the coast of Venice, Florida.

"They’re very far offshore. They’re not close to the beach," Hueter said. "It’s very unusual for these animals to come within 20 miles. Most of the time, they’re going to be 50 to 100 miles out."

Hueter speculates that red tide keeps great whites away from the shore because they are vulnerable to disease.

While great whites are farther out in the gulf, there are many other sharks much closer to shore. Researchers are seeing more sharks than they have in decades.

"There’s millions because we’re talking about lots of species," said Dr. Demian Chapman of the Mote Center for Shark Research.

Scientists say sharks see more of us than we do of them.

"I think a lot of people would be surprised, you have a packed-out beach with people in the water and then if you put a drone up, there’ll be a shark not that far away or even multiple sharks," he said.

Nick Bailey, 17, documented his face-to-face encounter with a great white while diving in Stuart Inlet. His Instagram video shows him touching the great white.

“We’ll see some bull sharks and sandbar sharks, but never anything like that,” Bailey said.

Florida is the shark bite capital of the world. Last year, 16 bites were reported in the Sunshine State. Addison Bethea, 17, lost her leg to a shark while swimming in 5 feet of water off Keaton Beach.

"I'm still going to get in the ocean when I heal and get better," Bethea said. "Still going to do what I love but don't just let fear overtake your life."

While sharks have increased, bites have not.

"The reality is if sharks wanted to feed on humans, they could do it all day every day and it would be a blood bath," Chapman said. "Not all sharks are these apex species. Most sharks are 3-foot long and they’re cute and cuddly to me."

While sharks may not be a significant threat to beachgoers' safety, an increasing number of anglers are concerned they are catching fewer fish and they blame protections put in place to save sharks.

"It is affecting their operations to have sharks stealing their fish off their lines or they’re catching more sharks than they care to," Hueter said.

In January, 12-year-old Campbell Keenan caught the biggest fish of his life, a great white off the coast of Fort Lauderdale.

"It did make me nervous," Keenan said. "I don’t know if I want to go up against a shark."

For decades, long-line commercial shark fishermen and sport fishermen reeled in millions of sharks.

“The problem was that way too much fishing happening because these animals reproduce very, very slowly," Chapman said. " We’ve estimated that about a hundred million sharks get killed per year by humans."

Today, with state and federal protections, the shark population has rebounded and Mote Marine scientists in Sarasota are seeing species of sharks they have not seen in more than 30 years.

“A little before Christmas of last year, I was pulling in the line and something enormous was on it and it was just pulling the whole weight," Chapman recalled. "It was a real tug of war. When the shark came up, it was about 12 feet long and everybody was crying out, 'It’s a this. It’s a that!' And then all of a sudden, it’s a Dusky shark and we all go nuts."

So far, Ocearch scientists have attached GPS trackers to 92 great whites. One of them is named “Bob,” in honor of Hueter. As sharks make a comeback, Hueter is heartened and hopeful for the future of sharks and the ocean they call home.

"I'm basically an optimist when it comes to the future of the planet," Hueter said. "We have to work hard though. We can’t just ignore the problems and we haven’t with sharks in the U.S. So, if we can do it with sharks, I think we can do it with just about anything."